Introduction

Community Health Workers (CHWs) form an emerging profession that has the promise of helping to fix some of the most significant faults of our health care system.[1] CHWs are of the community of largely poor, often of-color population alienated from and sometimes poorly served by our technically sophisticated but increasingly distant institutions of care.[2] One of the strengths of CHWs is that they can assist in a shift in care for the underserved from fragmentation to integration allowing medical services and social services to relate in recognition of the complex causes of the poor health status of the poor, including social determinants of health[3] (SDOH) effects as much as or more than medical conditions.[4] Improving their communities’ health status can involve the creation and support of integrated care systems that knit together medical and behavioral care with social services. Much has been written about such team-based care,[5] including by this writer.[6] CHWs can be contributors to the success of such ventures.

This paper’s modest goal is to describe and propose solutions to two difficulties that can arise when CHWs are used to further the largely admirable effort to create whole-person, integrated health care systems in part by recognizing the need to address social, as well as medical, barriers to good health status. The first difficulty is that the absorption of CHWs into large health enterprises can threaten to undermine an important source of CHWs’ value: their independence to act as of-the-community advocates and bridge-builders for people experiencing a gulf between themselves and established health and service systems (and community members’ recognition of CHWs’ independence).[7] Second, such absorption can foster or further the medicalization of socially-created problems, such as inadequate housing stock, food deserts, and inadequate schools – that is, it can contribute to the sweeping into health systems’ range of authority social services provision that has historically been the purview of separate, hopefully expert, social service providers and advocates.[8]

How can these two dangers – the loss of an essential value of CHWs and the medicalization of social care – be avoided? Carefully, and with thoughtful planning. This paper will suggest a possible structural response to these dangers, drawing on the work of organizations that support CHWs by connecting them to health and social service organizations while preserving their range of independent action on behalf of their communities. This proposed solution is not meant to suggest an exclusive professional path for CHWs. CHWs are members of an emerging profession, and some may choose to become integrally related to health care systems and participate in a clinically-oriented workplace with the attendant hierarchies. But some CHWs may prefer a role distinct from (although conversant with) the health care delivery system as a community representative and, importantly, as an intermediary between communities often alienated from health systems[9] and those systems’ clinical services. Both paths should be open to CHWs, and both serve important social functions.

The first part of this paper will describe who CHWs are, their roots as a profession, the roles they perform in today’s health and social service context, and the work underway to create sustainable funding paths for their work in their communities. Second, this paper will briefly review the integrated care models that have emerged to combine health and social services for the benefit of underserved communities and the place CHWs have found within those models. Third, it will describe two problems the absorption of CHWs into health systems can create: the possible weakening of the community-centric nature of CHW work and the dangers of medicalizing socially-generated determinants of poor health status. Fourth, it will describe a model for connecting some CHWs to health and social service organizations that can both preserve the integrity of the CHW model and provide an alternative or counterweight to a dominant model in which services directed to ameliorating the non-clinical problems created by SDOH are channeled through health systems in part through the work of CHWs. The model described in the fourth part of this paper inevitably adds complexity to already very complex medical and social service systems. But the structures described can serve an important function by permitting community-based organizations (CBOs) employing CHWs to deliver care in a way that is fiscally and managerially independent of health systems, but that maintains linkages to assure that funding flows to the CBOs for CHW services; information flows from the CBOs to payers for the services (including insurers and health systems); and professional independence is maintained for those CHWs who choose to remain community-based in local CBOs.

I. Who are CHWs, and what do they do?

The American Public Health Association defines CHWs as,

frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables CHWs to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery. CHWs also build individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy.[10]

CHWs, also called promotores de salud, lay health advocates, community health representatives, and peer health educators, among other titles,[11] perform a wide array of services and tasks, including health care coordination, health coaching, providing social support, resource linkage, care management, targeted health education, and health literacy support.[12] The CHW model has long existed in other nations, in which its importance to advancing goals of wellness and whole-person health is widely recognized.[13] In the United States, CHWs historically have served many social and health-related roles.[14] These roles are distinct from other helping professionals such as social workers and nurses. Unlike licensed professionals, CHWs do not prepare by pursuing an academic degree. Instead, they are qualified by dint of deep community connections and familiarity and personality traits, such as empathy, leadership, and communication skills[15] as well as widely disparate, often short-term training programs focusing on background issues (patient privacy, ethics) and targeted knowledge bases (health fact about Covid-19 or other diseases; information about housing, nutrition, and social service providers).[16] Training is sometimes on the job and sometimes provided in classroom settings direct to core competencies, such as communication skills, advocacy skills, and teaching skills.[17] Their core functions include the provision of culturally relevant health education; service as a bridge between community members on one hand and health providers, social service agencies, and government on the other; advocacy for improved services with and on behalf of community members; navigation assistance for community members seeking services; and home visitation to evaluate and assist in the assessment of the health status of community members.[18]

CHWs, often in partnership with other health systems or CBO employees, can perform many specific outreach tasks to facilitate enrollment in government or private benefits programs; under the supervision of clinicians, monitor adherence to medications or other health interventions; canvassing and other activities to further health research; and with clinical and social service partners, the evaluation and assessment of existing health and social services.[19]

Although CHWs are widely seen as effective in addressing health inequities and improving access to care for poor communities,[20] the evidence is spotty, in part because CHWs perform a broad range of services that can vary from setting to setting[21], making apples-to-apples comparisons difficult. In the context of membership in team-based primary care and integrated care settings, CHWs are seen as providing important patient education and “bridging” functions.[22] Less is known about CHW work that is not clinically related, as the benefits are likely to be more diffused and the activities of CHWs more difficult to standardize for evaluation purposes.[23]

Interest in the work of CHWs has been responsive to the understanding of the extent of the inequities in our health care system. In communities of color, particularly Black and Hispanic populations, outcomes lag – sometimes significantly – from outcomes experienced by White cohorts in many areas, including maternal-child health, infectious diseases, and morbidity and mortality related to poorly controlled chronic illness.[24] The reasons for these disparities are obviously complex but include social and political determinants of health in poorly-served populations, histories of explicit and socially embedded racism, and the effects of an economically skewed society.[25]

CHWs are of these underserved communities and therefore are able to fully grasp the communities’ concerns and are able to credibly guide community members as they seek to gain appropriate access to medical care and social services.[26] Social determinants of health, and “upstream” barriers to good health status, obviously affect all classes and ethnic groups.[27] Poverty and racism are powerful determinants of health status, and therefore poor communities and communities of color are most affected by unaddressed social determinants.[28] CHWs’ work in these communities is increasingly important as the injustice of the health deficits experienced in them are more clearly delineated. The next section describes one use of CHWs for these underserved populations.

For whom do, and should, CHWs work? The name of their profession – community health worker may suggest that they are largely connected to workplaces engaged in the delivery of clinical health care. While many are, they are also employed by non-health care CBOs, charities, faith-based organizations, and other service organizations that do not deliver clinical care.[29] A recent survey of places of employment for CHWs found that, in the study sample, health care delivery entities comprised about 58% of the settings employing CHWs, while CBOs and other nonprofit agencies comprised about 38%, and public health and social agencies accounted for the balance.[30] This distribution, the researchers noted, may overstate the dominance of health delivery settings as employers; they found that health providers tended to each employ fewer CHWs, and therefore, the balance between CBOs and health care providers as CHW employers was closer to equal.[31]

To the extent that this study is somewhat representative of places of CHW employment, it seems that CHWs’ performance of their historic and ongoing tasks of assisting members of impoverished, vulnerable, and/or underserved populations occurs in both clinical and non-clinical settings.[32] The next section addresses the substantial benefits of the use of CHWs in clinical settings and, in particular, those that engage in integrated, whole-person models of care.

II. Closing gaps for the underserved: use of CHWs in whole-person care delivery

As is described above, CHWs have worked with community members in CBOs, such as churches, schools, community centers, and housing organizations.[33] In those settings, CHWs were genuinely enmeshed in their communities and were easily seen as independent advocates for their fellow community-members, who they often knew and by whom they were known.[34] Over time, the recognized ability of CHWs to improve the health status of underserved and vulnerable communities led to their increasing connection with the health care delivery system, under the reasonable assumption that clinicians and CHWs served similar goals of improving individuals’ health status and that their joining forces might improve care.[35]

The adoption of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) played a part in encouraging the use of CHWs as an aspect of its encouragement of health providers to think of their mission in a different way. One of the central features of the ACA is its focus on health equity and the need to close the gap between the health status of underserved populations, including the poor and populations of color, and the higher health status of White and non-poor Americans.[36] An important tool for achieving that goal is the ACA’s embrace of coordinated, whole-person care, in which caregivers treat the entirety of the patient’s health issues as a team.[37] One key aspect of the ACA in this regard is its support for the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model of primary care.[38]

PCMH programs and other integrated care primary care models supported by the ACA can remediate the historical shortcomings of the health care system for vulnerable populations. As one commentary written shortly after the ACA’s enactment stated,

Care delivery models for vulnerable populations should reflect the most effective strategies identified by the latest empirical research. There is evidence that much of the disparity in care experienced by vulnerable populations could be eliminated through the provision of patient- and family-centered primary care that emphasizes team-based care, care coordination, care management, and preventive services (e.g., care delivered through health homes and patient-centered medical homes).[39]

PCMH projects were adopted in many states early on in the ACA’s life, as states embraced enhanced primary care as a tool for addressing Medicaid populations’ health deficits.[40] They also form the basis for larger-scale reforms, such as Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations, through which PCMHs coordinate with other providers, including hospitals and specialty providers, to further integrate care.[41]

CHWs have become a part of the movement to use team-based integrated care to address the health needs of underserved and medically complex patients. The connection between underservice and complexity of need is direct: those whose medical and social needs have been poorly addressed may suffer not only from lack of access to primary and preventive care but from high rates of chronic conditions and social service shortfalls that would benefit from focused attention.[42] In a sense, then, well-designed team-based care for underserved people can be a corrective for the system’s previous failure to adequately provide primary and preventive services, but also as a reparative for the harms that have been visited by past structural deficits in treatment and service equity.

Underserved persons often display a range of complex health needs flowing from the effects of social determinants and their poor access to medical and social services. The treatment of people with complex health needs therefore benefits from team-based models, with cooperative approaches integrating care by physicians, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and others.[43] As recognition of the importance of social determinants has increased, CHWs have been added to this suite of caregivers.[44] As Jessica Mantel has described, these integrated care models for the underserved often embody,

a holistic approach to health that goes beyond the traditional focus on medical needs. Specifically, they address the full spectrum of patients’ health-related needs, coordinating care across the health care, public health, and social services sectors, and linking patients to community resources. This approach relies on multidisciplinary care teams that may include clinicians, behavioral health specialists, social workers, community health workers (CHWs), and other health-related professionals.[45]

There is support in the literature for the use of CHWs in these team-based primary care settings. A 2015 Institute of Medicine discussion paper spoke of the integration of CHWs into primary care in glowing terms:

We have an innovation that is showing tremendous gains in improving health, especially among vulnerable populations. It has produced a return on investment of 4:1 when applied to children with asthma and a return on investment of 3:1 for Medicaid enrollees with unmet long-term care needs. . . . In fact, examples keep emerging from around the country about its effectiveness in improving health outcomes and reducing emergency room visits and hospitalizations. *** If these were the results of a clinical trial for a drug, we would likely see pressure for fast tracking through the FDA. . . . *** Instead, despite the promise this innovation has shown for years . . . it still has not been widely replicated or brought into the mainstream of U.S. health care delivery. *** The innovation is the use of community health workers (CHWs), and, more specifically, their integration into team-based primary care.[46]

Some researchers who advocate for CHWs in primary care focus on the important role they can play in addressing past and ongoing inequities in the health care delivery system and decry the failure of payers to support their integration into primary care:

As trusted members of the communities where they live and work, with whom they share common racial and ethnic backgrounds, cultures, languages, and life experiences, CHWs are well positioned to help people receive timely care by facilitating access to primary and preventive services and by improving the coordination, quality, and cultural competence of medical care. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of CHWs, meaningful integration into the health care delivery team has eluded them [due to lack of funding to support their work].[47]

Others agree that experience with CHWs in primary care is quite promising: “[T]here is robust evidence of CHWs’ impact, demonstrating that support from CHWs can contribute to reduction in several chronic diseases, improvements of quality of care, self-rated mental health, and reduced hospitalizations.”[48]

While the most common health care placement for CHWs appears to be in primary care practices, they also find employment with insurers (as outreach and care management workers for high-cost insureds) and in hospitals (as outreach and patient support workers for patients with complex conditions).[49] Some hospital programs pair CHWs with patients with complex health or social needs in programs that see CHWs visit patients at home following a hospital discharge. Hospitals have reported that such programs reduce readmissions and visits to emergency departments.[50] In several states, Medicaid supports – or requires – Medicaid managed care plans’ direct employment of CHWs as outreach and patient education workers.[51]

The most studied area of CHW work is in the health care delivery system and specifically in the primary care/integrated care settings, whose goal is to improve the health status of historically underserved populations.[52] As CHWs have become enmeshed in and identified with the health care delivery system, two concerns arise regarding their public reputation and roles. First, does absorption by health care organizations weaken the community-centric nature of CHWs’ expertise and value by distancing them from their communities and identifying them with systems from which underserved patients may well feel alienated? And second, does the absorption of CHWs into the health care system contribute to the concern that delegating responsibility for social concerns, such as inadequate housing or lack of transportation, contributes to the concern that social services are inappropriately medicalized by identifying social needs with a patient’s condition thereby diverting focus from inadequate social investment? Those two questions are addressed in the next part.

III. Resolving roles: CHWs in and of the community or the health system

This part addresses two concerns with the increasingly close identification of CHWs with health care delivery and, therefore, with the organizations and systems in charge of health care services. This part is motivated by concerns that such identification can diminish the effectiveness of CHWs, and that over-incorporation of SDOH attention into health care can weaken broader social movements to improve the living conditions of the poor and vulnerable. Two caveats at the outset. First, I am a believer in the promise of PCMH and other primary care integrated programs for underserved populations, including those that use CHW services. Indeed, I work closely with state agencies, advocates, and care providers in New Jersey in a project that seeks to advance the use of CHWs in a variety of settings, including health settings.[53] Second, my observations about the dangers presented by the employment of CHWs in health organization settings are intended to identify undertheorized textures in the relationship of CHWs to health and social services, thereby strengthening the ability of CHWs to contribute to their communities’ health status. The complexities raised here lead to the discussion in Part IV of this paper, in which I attempt to resolve – or at least address – the concerns raised here.

A. Helping whom? Sticking with the community and independence

Differences by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in health access and outcomes are well-established. In communities of color, particularly Black and Hispanic populations, outcomes lag – sometimes significantly – from outcomes experienced by White cohorts in many areas, including maternal-child health, infectious diseases, and morbidity and mortality related to poorly controlled chronic illness.[54] The reasons for these disparities are obviously complex but include social and political determinants of health in poorly-served populations, histories of explicit and socially embedded racism, and the effects of an economically skewed society.[55] In addition to background economic and social inequities, racism in health care delivery is real and can have deadly effects[56] and permeates all levels of health care.[57]

The question arises, then, how CHWs, whose roots are in communities and their CBOs, will maintain their community connection, credibility, and effectiveness if they become part of the health care delivery system. The recent history of CHWs’ deployment suggests tensions about their role – are they to amplify and translate community concerns and serve as trusted resources for their communities, or are they to facilitate health care delivery? As is described above, team-based integrated care can provide care and connections to social services that can reduce vulnerable populations’ disadvantages in access and help to repair the harms done as a result of historical racism and unresponsive treatment.[58] But absorption into a clinical team can blur or frustrate the efficacy of their translational and advocacy efforts.[59] CHWs and those advocating for their more robust deployment must “consider the trade-offs between emphasizing prevention and upstream issues versus primary care and other health-care interventions, as well as between improving the communication and responsiveness of clinicians on the care-giving team of individual patients versus advocating for the health needs of the whole community.”[60]

There are several difficulties wrapped into this problem. First, CHWs’ historical community respect and effectiveness has not been due to their formal credentials and education but rather to their recognized goodwill, commitment, knowledge of the community, and independence of voice.[61] Entering health care settings, particularly as part of a care team that is paid by Medicaid or other payers for services to enrolled patients, CHWs are likely to be required to obtain some credentials in the form of educational attainment, training in matters such as patient privacy and recordkeeping, and perhaps background checks. These indicia of formality can grate on the ethos of independence and informal community presence that is a strong root in the history of CHWs’ development as a profession.[62] Health organizations tend to have more formal and rigorous human relations policies, in part because they are very heavily regulated in comparison to most CBOs. [63] The employment by health organizations of CHWs, therefore, sets in motion tendencies to formalize the status of CHWs, perhaps to the detriment of their community effectiveness, but almost certainly to the detriment of health organizations’ ability to hire and retain community members with skills and capacities developed on the streets rather than in schools.

In a 2016 paper, Canadian researchers juxtaposed two models of CHW collaboration with the health system: an independent model and an integrated model. They described the independent model as comprising,

[I]ndependent organizations, often established by CHWs themselves, [which] offer services that target marginalized communities. These organizations and the CHWs working within them obtain contract funding to deliver their services independently of public healthcare institutions, but often in collaboration with them. When funded, organizations retain complete autonomy in the work’s conceptualization and programming. *** Independent models are marked by high levels of health promotion activity, as distinct from a focus on specific service delivery. The main health system’s concern with independent models is that they may have less accountability and supervision, and that the CHWs may have less training, than CHW program delivery through integrated models. Furthermore, given the lack of resources, it may also be more difficult to evaluate service outcomes in independent models.[64]

In contrast, in the integrated model,

CHWs are staff within public health or primary care institutions, which have as part of their mandate the delivery of programs targeting populations experiencing marginalization. . . . These workers are usually well-paid with good benefits, as well as reasonable work hours and caseloads, which is often not the case for CHWs operating in independent models. Generally, CHWs and their professional allies in public health units reach out to marginalized communities with specific programs and key health messages.[65]

In these terms, the independent model would see CHWs work for a CBO not affiliated with a health system and engage with community members as advocates and allies, but without the direct resources or guidance of clinical staff attempting to address specific health needs of the same population.[66] In the integrated model, CHWs enjoy the resources and guidance of clinical workers but at the expense of the loss of real and perceived independence.[67] At one extreme, the independent model could result in a disconnect from the health system in a way that is detrimental to the community served. At the other extreme, CHWs risk becoming so enmeshed in the broad health system to the extent they will be so disconnected from their communities as to lose their unique value.

Compromises have been adopted and proposed.[68] Two categories of possible solutions suggest themselves, neither naturally perfect.[69] In one, CHWs become employees of health care entities.[70] The trade-off of clinical partnership for primary community commitment is, then, taken, and CHWs add their skills and capabilities to the laudable enterprise of integrated, whole-person care[71] at the expense of personal independence and primary loyalty to their communities. In the second, CHWs remain independent from health enterprises, employed by CBOs independent of health care entities, and embedded in their communities.[72] The trade-off here is one by which independence and community loyalty are preserved but at the expense of close partnership with clinical providers.[73] I will discuss a possible structural solution in Part IV that certainly describes a structure adopting the second course of action and that allows for collaboration with health providers.

B. Avoiding medicalization of poverty

The issue of the “medicalization” of poverty as evidenced by substandard housing, the absence of work with living wages, food deserts, and poor primary and secondary schooling, has been the subject of scholarly discussion in recent years.[74] Although the definition of medicalization in this context is contested,[75] discussions of medicalization are intended to address two concerns. The first is that a modern concept of medical care tends to treat symptoms of poverty, “that is, the illnesses resulting from poverty, rather than the underlying cause, of poverty.”[76] This may undercut the actors attempting directly to remediate, for example, housing shortages in favor of case-by-case patch-ups of the problems experienced by individual patients. The second concern addressed by medicalization discussions is “the stigmatizing . . . effect of turning everyday life events into something pathological by describing it in medical terminology.”[77] Some commentators see the shift of social problems to the medical sphere in some situations as a good – or at least not an unalloyed bad.[78] Others see it as a very bad thing indeed.[79] In this Part, I use the above definitions of medicalization and describe the dangers that might accrue to CHW practice and the communities CHWs serve as a result of CHWs’ close association with health care delivery systems.

The absorption of CHWs into the health care system could further the medicalization of poverty by transferring CHWs’ efforts to ameliorate poverty from the community and CBOs to health care providers. That is, this transfer of the locus of CHW activity from the community to health organizations could shift the meaning of poverty (as described above) from the societal failure to adequately ensure the provision of safe and affordable housing, appropriate schools, opportunities to obtain nutritious food, and opportunities for exercise and recreation, and instead, locate poverty in the patients themselves as one of series of symptoms.[80] In this way, poor housing, for example, becomes a patient-specific cause of poor health to be addressed through a health system and not an indication of a need for action by a housing agency or a broader demand, supported by the society-wide experience of unjust or inefficient resource allocation, that social problem should be solved by social service agencies or legislatures.[81]

There are at least two harms that could be threatened by this medicalization. One is the psychic harm created by the suggestion that external social deficits are pathologies of the individual – that the failure to find work in an employment desert or to send a child to a suitable school in a neighborhood without one – is a symptom of personal failure or illness.[82] This effect could further stigmatize and subject to opprobrium the poor and underserved the enterprise of integrated primary care was seeking to assist.[83]

The second harm medicalization could do in this context is to sap the strength of community-based advocacy and service organizations formed and operating to advance housing, food, education, and employment justice, as well as those that combat spousal violence, overcriminalization, and racial injustice. If the work of those organizations is incorporated into the work of health care entities, and the funding for the work of those organizations is channeled through health insurance programs, long-term expert advocates and service providers could be weakened. But these serious concerns cannot eclipse the social benefit offered when CHWs work with integrated care providers to remediate the individual effects of society’s neglect of social service shortfalls. I address approaches to avoiding these harms in the next part.

IV. Coordination, intermediation, and sustainability

The roles played by CHWs in improving the lives of poor and underserved populations who experience unsatisfactory connections with health care providers are many and complex.[84] They are the most visible manifestation of the observation that the health status of these populations is driven as much (or more) by social problems such as poor housing, schools, and nutritious food – as well as overarching stresses from racism and unsafe neighborhoods – than it is by access to medical care.[85] Models of integrated primary care that emphasize multi-disciplinary team care can be very helpful in addressing the poor health status of these populations.[86] CHWs play an essential role in addressing those health status deficits, whether as part of the multidisciplinary teams or as contractors who can be called upon to serve as a distinct bridge between the communities and the caregiving team – or both.[87]

This part will suggest a mechanism that can address some of the concerns raised in this paper – that incorporation into clinical entities will weaken the community-centeredness of CHWs, and that the incorporation of CHWs and their roles within health care organizations can medicalize social issues such as poverty and racism that are causative of the populations’ poor health status. The structural solution described here is not meant to be an exclusive mechanism for CHWs’ work. There is certainly room for some CHWs to choose to practice outside health organizations and in CBOs and communities, while others are embedded in health firms.

One factor that emerges in any attempts to support CHWs’ work in settings commensurate with their professional identities is the need for a sustainability strategy for CHWs. Many CHWs are supported by grant funding,[88] a relatively unstable base on which to build the broad deployment of the members of this emerging profession. CHWs usually do not themselves bill health insurers, and their services are only recently becoming part of alternative payment models that include support for their work.[89] The Willie Sutton factor[90] drives some of the emphasis in the Part on the health delivery and insurance systems. If sustainable funding is the goal, health care settings are the entities that receive regular, substantial payments that can support work related to improving health status. Funding from Medicaid and other health payers and organizations will be an important part of any sustainability strategy for CHWs’ work.[91]

A. Intermediary “back office” organizations to facilitate and support

To be most effective, CHWs need to be independent enough to maintain connection and credibility with their communities, have access to funding to support their work, and have close relationships with health providers serving the CHWs’ vulnerable communities. It may be that becoming enmeshed with a health care organization presents sufficiently significant threats to the independence of CHWs to counsel caution in that regard and that some CHWs will therefore seek to practice outside health care settings.

CHW practice outside the ambit of entities supported by public and private health insurance protects CHWs from the harms described above but creates other problems. It is likely that small community-embedded CBOs can permit CHWs to flourish, but they likely lack several skills or capacities useful or essential to CHWs’ ability to be maximally effective: the ability to connect with health firms and insurers[92] to obtain referrals for community members in need of services; the financial sophistication to bargain for and receive payment from those same sources; the capacity to manage, analyze, and transmit data on the services provided in the community and the results of the services on the community members; and the ability to organize the certification and credentialing information on CHWs health entities might require to pay for their services.[93]

Models of intermediation have arisen to facilitate interactions between health payers (including public and private insurers, health systems, and government agencies) and CBOs and other non-health care entities working in the communities in which CHSs flourish. Without these mediating entities, CHWs may well find the path to sustainable income difficult or impossible, and health payers may find it frustratingly complex to contract for CHW services and obtain reliable information on the services provided by CHWs entitling them to payment. An example of such an organization is the Pathways HUB model.[94]

In the Pathways HUB model, an intermediary (the HUB) is a local agency that has or can acquire an understanding of the mission, capabilities, and expertise of CBOs providing care in a geographic region.[95] The HUB is able to gather and monitor information regarding the qualifications and capacities of these CBOs in order to inform health systems and insurers of the community resources available to address needs associated with social determinants of health, direct referrals from health systems and insurers to CBOs, gather information on the success of each referral, and analyze and transmit that data.[96] The HUB is equipped to negotiate contracts with health organizations and insurers and, in turn, with the CBOs.[97] Large health organizations and insurers are unlikely to have the ability and/or interest in contracting with hundreds of CBOs; the HUBs can organize and represent the CBOs in one area served by the larger organizations.[98] And as the CBOs are unlikely to be able or inclined to transmit certification and other identifying information or outcomes data in uniform and usable formats, the HUB performs those functions.[99]

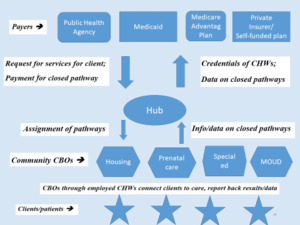

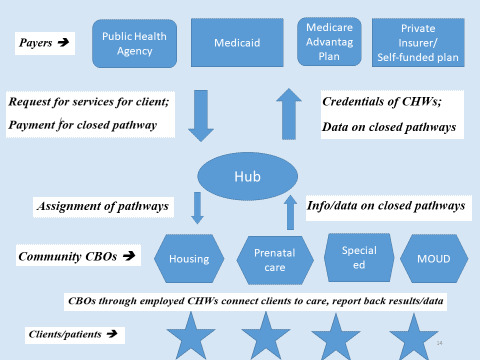

The intermediary function is represented in the following graphic:

The Pathways HUB model is in operation in several locations in Ohio[100] and San Antonio, Texas,[101] and a similar structure operates in San Diego, California.[102]

These intermediaries serve the “back office” functions small CBOs and individual CHWs are ill-equipped to perform while protecting the independence of CHWs and providing a sound pathway for sustainability for CHW work.[103] The CBOs are contractors independent of health care entities.[104] They allow community-based CBOs to continue to employ CHWs to assist community members.[105] When the needs of the community members coincide with health entities’ diagnosis of shortfalls in social services or social connections, the CBOs can accept discrete tasks to connect community members with local social service entities or to serve as bridges between sometimes reluctant community members and health care providers.[106] The intermediary engages in contracting “up” with payers and “down” with CBOs; they gather credentialing information that payers may need to justify payments for services; they provide individual and aggregate information on completed (or failed) referrals back to payers; and they collect payment from payers for services and transmit those payments (less a service charge) on to the CBOs.[107]

Through this intermediary mechanism, CHWs can maintain their independence to work with local, non-health-related CBOs while providing services to facilitate the success of integrated care by health providers.[108] The intermediaries provide the “back office” expertise in data collection and analysis, contracting, and maintenance of credentialing information for the community CBOS.[109] They relieve health payers (including health delivery systems) from the difficulty of contracting with large numbers of (often small) CBOs while preserving health payers’ ability to obtain the services of community CHWs and to obtain data on credentials and completed (or failed) referrals.[110] This second-best solution allows a degree of CHW independence while facilitating the goal of integrated health systems to address the effects of SDOH impairing their vulnerable patients’ health status.[111]

B. Inside the team – with support and recognition of community-voice role

Some CHWs may, notwithstanding the option described above, choose to practice within integrated primary care teams for at least two reasons. First, integrated care practices are up and running with employed CHWs, and those system developments are unlikely to be unwound.[112] Second, the value of CHW team members is likely to enhance the effectiveness of those forms of care delivery, as researchers and commentators have described.[113]

Practices employing CHWs should integrate them carefully in order not to diminish their effectiveness as team members.[114] It is important to note that their value is not just their cultural sensitivity – it is possible, indeed essential that other team members are also culturally sensitive to the backgrounds and needs of the historically underserved populations from whom their patients are drawn.[115] CHWs are different; they actually come from the community and therefore have a bank of knowledge, a font of awareness, and a foundation of trust that other members of the team, no matter how well-intentioned, are unlikely to possess.[116] One danger of the integration of CHWs into health systems is that the credentialing and hierarchy in many health systems may threaten a core value of CHWs – that their strengths come not from formal education or credentials but from experience and connection with the community.[117] Forcing CHWs (as square pegs) into health systems’ credentialing and hierarchical structure (as a round hole) could “potentially threaten what makes CHWs unique—the trust of the community served. This would represent a significant break with the historical roots of the CHW movement and could create barriers to entry into the profession.”[118]

With thoughtful planning and intentional management decisions, the value of CHWs can be maintained while allowing the practice’s patients to benefit from the presence of CHWs on the team. Cheryl Garfield, a senior CHW, and Shreya Kangoyi, a physician with experience working with CHWs, have described a modus vivendi allowing for the coexistence of CHW and clinical work in health care settings.[119] Both authors are affiliated with the Penn Center for Community Health Workers, housed at the University of Pennsylvania, one of the preeminent sources of research on the training and deployment of CHWs.[120]

Garfield and Kangoyi describe agenda-setting between CHWs and clinical and management staff as a critical step in ensuring appropriate CHW deployment:

Maintaining an identity as a CHW means not allowing the health system to set the expectations of how CHWs should service their patient population. Health care leaders, clinicians, and community members will likely have different opinions about the goals of a CHW program. Health systems often see these programs as a way to lower costly hospital readmissions. Clinicians tend to view CHWs as promoters of specific health interventions or behaviors, such as mammograms, vaccines, and medication adherence. CHWs meanwhile may have a broader agenda that includes providing social support and addressing the resource inequities—such as income, housing, and education—that lead to poor health in the first place. *** Modern CHW programs must continue to thread the needle between these top-down and bottom-up frames.[121]

They also urge that clinicians and management keep the unique skills of CHWs in mind in allocating responsibilities and scopes of work:

Even authentic CHWs can become medicalized if their role is not appropriately defined. . . . Some [clinicians] may view CHWs as simply a way to task-shift to the “lowest common denominator.” In such a scenario, CHWs risk becoming just another cog in the clinical wheel: scheduling appointments, pinging patients to take their meds, or even performing menial tasks.[122]

Recognition and employment of CHWs’ skillsets might best be ensured, they argue, by using social workers trained in CHW work to supervise and perhaps train CHWs, and to ensure that CHWs are consulted on practice management and patient care decisions.[123]

While much of the literature describes the integration of CHWs into health organizations from a patient perspective, it will be important for caregivers to take care in integrating CHWs into clinical settings to consult with CHWs and experts in CHW practice in order to ensure that the skills of CHWs are properly recognized and utilized and to guard against the depletion over time of one of the CHWs’ sources of capital: their ability to recognize the community and be recognized in it.[124]

Conclusion

This paper recognizes the importance of both CHWs and integrated primary care teams as means to address the effects of social determinants of health on historically underserved populations. Both CHWs and integrated care practices are essential in remediating the historic injustices in both health care and the broader society that have served as barriers to the improvement of the health status of communities of color, the poor, and other underserved and alienated populations.[125]

CHWs and integrated primary care teams are often linked because the community-based skills of CHWs can bridge the gap between underserved populations and the health care delivery system, including integrated primary care teams.[126] This paper suggests two cautions: First, the complete absorption of CHWs into health systems risks degrading or neglecting the unique skills they bring to health equity efforts.[127] A model for facilitating the independence of CHWs from health systems while facilitating their service to the goals of integrated care exists in the form of community nonprofits serving as intermediaries between CHWs and clinical care.[128] These intermediaries can perform “back office” work for CHWs, allowing CHWs maximum independence of action while serving the needs of patients of integrated care practices.[129] Second, for those CHWs who prefer to be employed by and integrated into health care entities, there is a danger that CHWs’ essential value will be degraded if they are treated as just one more category of clinician or clinical helper within a health care practice.[130] The integration of CHWs into health care entities should be accomplished through thoughtful clinical protocols and CHW supervision to protect the unique value of CHW work.[131] CHWs are not simply additional clinicians; rather, they best function as a bridge between clinicians and skeptical communities.[132]

CHWs can be important forces in improving care for poor and vulnerable populations – a goal shared by integrated care practices. The meshing of clinical work and CHW practice must be done delicately and with forethought. The payoff for communities if care is taken can be substantial.

Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities, Am. Pub. Health Assoc. (Nov. 10, 2009) [hereinafter Support for CHWs], https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities.

See Community Health Workers in Rural Settings, Rural Health Info. Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/community-health-workers (last visited Feb. 6, 2023).

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, racism, climate change, and political systems. Social Determinants of Health at CDC, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (Dec. 8, 2022), https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html; see also Social Determinants of Health: Overview, World Health Org. [WHO], https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (last visited Aug. 14, 2023) (defining social determinants of health); Hugh Alderwick & Laura M. Gottlieb, Perspective: Meanings and Misunderstandings: A Social Determinants of Health Lexicon for Health Care System, 97 Milbank q. 407 (2019) (defining social determinants of health).

Support for CHWs, supra note 1.

See e.g., Jessica Mantel, Leveraging Community-Based Health Teams to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Populations in Times of Crisis, 30 Annals Health L. & Life Sci. 133 (2021).

See John V. Jacobi, The Tools at Hand: Medicaid Payment Reform for People with Complex Medical Needs, 28 Annals Health L. & Life Sci. 135 (2019).

See Support for CHWs, supra note 1.

See text, infra notes 75-79.

See Support for CHWs, supra note 1.

Support for CHWs, supra note 1.

See Randall R. Bovbjerg et al., The Evolution, Expansion, and Effectiveness of Community Health Workers 5 (2013), Urb. Inst., https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/32556/413072-The-Evolution-Expansion-and-Effectiveness-of-Community-Health-Workers.PDF; Emma K. WestRasmus, et al., Promotores de Salud and Community Health Workers: An Annotated Bibliography, 35 Fam. Comm. Health 172, 172 (2012).

Andrea Hartzler et al., Roles and Functions of Community Health Workers in Primary Care, 16 Annals Fam. Med. 240, 242 (2018).

See Prabhjot Singh & Dave A. Chokshi, Community Health Workers — A Local Solution to a Global Problem, 369 New Eng. J. Med. 894, 894 (2013). CHWs have long-served population health roles globally. See Zulfiqar A. Bhutta et al. World Health Org, [WHO], Global Experience of Community Health Workers for Delivery of Health Related Millennium Development Goals: A Systematic Review, Country Case Studies, and Recommendations for Integration into National Health Systems (2010); see generally, John V. Jacobi & Tara Ragone Adams, Seton Hall Univ. Schl. L., Community Health Workers in New Jersey: The Question of Certification (2019), https://issuu.com/seton-hall-law-school/docs/sh-law-chw-report-110719.

See Leda M. Pérez & Jacqueline Martinez, Community Health Workers: Social Justice and Policy Advocates for Community Health and Well-Being, 98 Am. J. Pub. Health 11, 12 (2008).

See Matthew J. O’Brien et al., Role Development of Community Health Workers: An Examination of Selection and Training Processes in the Intervention Literature, 37 Am. J. Prev. Med. S262, S264 (2009).

See Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities, supra note 1; Jacobi & Ragone, supra note 13, at 5.

See Bovbjerg et al., supra note 11, at 7.

See, Cara Whelan Smith et al., Ohio Dep’t of Health & Ohio Coll. of Med., The 2018 Ohio Community Health Worker Statewide Assessment: Key Findings (2018), http://www.nursing.ohio.gov/PDFS/CHW/Assessment/1_CHW_Assessment_Key_Findings.pdf; C3 Project, Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project (2016) [hereinafter “C3 Progress Report”], http://chrllc.net/id12.html; N.C. Cmty. Health Worker Initiative, Community Health Workers in North Carolina: Creating an Infrastructure for Sustainability 8 (2018), https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/DHHS-CWH-Report_Web 5-21-18.pdf; William M. Sage & Kelley McIlhattan, Upstream Health Law, 42 J.L. Med. & Ethics 535, 544 (2014); Sally E. Findley et al., Building a Consensus on Community Health Workers’ Scope of Practice: Lessons From New York, 102 Am. J. Pub. Health 1981, 1983 (2012).

See Hannah Covert et al., Core Competencies and a Workforce Framework for Community Health Workers: A Model for Advancing the Profession, 109 Am. J. Pub. Health 320, 322 (2019) (describing stratified categories of CHWs); C3 Progress Report, supra note 18, at 2; Findley et al., supra note 18 at 1983.

See Shreya Kangovi & David A. Asch, The Community Health Worker Boom, Cmty. Catalyst New Eng. J. Med. (Aug. 29, 2018), https://catalyst.nejm.org/community-health-workers-boom/.

See Samantha Sabo et al., Community Health workers in the United States: Challenges in Identifying, Surveying, and Supporting the Workforce, 107 Am. J. Pub. Health 1964 (2017).

See Luz Adriana Matiz et al., The Impact of Integrating Community Health Workers Into the Patient Centered Medical Home, 5 J. Primary Care & Cmty. Health 271, 273 (2014); Sally Findley, Integration Into the Health Care Team Accomplishes the Triple Aim in a Patient-Centered Medical Home: A Bronx Tale, 37 J. Ambulatory Care Mgmt. 82, 89 (2014).

See Samantha Sabo et al., Community Health Workers in the United States: Challenges in Identifying, Surveying, and Supporting the Workforce, 107 Am. J. Pub. Health 1964, 1968 (2017).

See generally National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, The National Academies Press (2017). See generally Institute of Medicine, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, The Nat’l Acad. Press (2003).

Id.; see also Daniel E. Dawes, The Political Determinants of Health, Johns Hopkins Univ. Press (2020).

Community Health Workers, Am. Pub. Health. Ass’n, https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (last visited Feb. 6, 2023).

See E.H. Bradley et al., American health paradox – high spending on health care and poor health, 110 QJM: Int’l J. Med. 61, 62 (2017).

See Bettina M. Beech et al., Poverty, Racism, and the Public Health Crisis in America, Frontiers in Pub. Health (Sept. 2021).

See Bovbjerg et al., supra note 11, at 5.

Mary-Beth Malcarney et al., The Changing Roles of Community Health Workers, 52 Health Serv. Rsch 360, 367 (2017).

Id.

See id.

See id. at 367.

Id. at 367-69.

Mary Pittman et al., Bringing Community Health Workers into the Mainstream of U.S. Health Care, Inst. of Med. Discussion Paper 2 (2015), https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/chwpaper3.pdf.

See Jesse C. Baumgartner et al., How the Affordable Care Act Has Narrowed Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Care, Commonwealth Fund Data Brief (January 2020), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Baumgartner_ACA_racial_ethnic_disparities_db.pdf.

See John V. Jacobi, Medicaid Evolution for the Twenty-First Century, 102 Ky. L. Rev. 357, 372 (2014).

See Karen Davis et al., How the Affordable Care Act Will Strengthen the Nation’s Primary Care Foundation, 26 J. Gen. Int. Med. 1201 (2010).

Edward L. Schor et al., Ensuring Equity: A Post-Reform Framework to Achieve High Performance Health Care for Vulnerable Populations, Commonwealth Fund (October 11, 2011), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2011/oct/ensuring-equity-post-reform-framework-achieve-high-performance.

See Mary Takach & Jason Buxbaum, Care Management for Medicaid Enrollees Through Community Health Teams, Commonwealth Fund 7 (May 21, 2013), http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund% 20Report/2013/May/1690_Takach_care_mgmt_Medicaid_enrollees_community_hlt_teams_520.pdf; Mary Takach, About Half of the States Are Implementing Patient-Centered Medical Homes for Their Medicaid Populations, 31 Health Aff. 2432, 2432 (2012); Kelly Devers et al., Innovative Medicaid Initiatives to Improve Service Delivery and Quality of Care: A Look at Five State Initiatives 1, Kaiser Family Foundation (Sept. 1, 2011), http:// kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/0 1/8224.pdf.

See Jacobi, supra note 37 at 374-76.

Alderwick & Gottlieb, supra note 3 at 408-09.

See Dennis Z. Kuo et al., Care Coordination for Children With Medical Complexity: Whose Care Is It, Anyway?, 141 Pediatrics 224, 224-232 (2017); Jacobi, supra note 37 at 141.

Mantel, supra note 5 at 240.

Mantel, supra note 5 at, 239-40 (citations omitted). Professor Mantel refers to these integrated care configurations as “community-based integrated health teams (CIHTs).” Id. at 239.

Pittman et al., supra note 35.

Jacqueline Martinez et al., Transforming the Delivery of Care in the Post–Health Reform Era: What Role Will Community Health Workers Play?, PMC 101 Am. J. Pub. Health e1, e2 (2011).

Caitlin G. Allen et al., Is Theory Guiding Our Work? A Scoping Review on the Use of Implementation Theories, Frameworks, and Models to Bring Community Health Workers into Health Care Settings, 25 J. Pub. Health Mgmt. and Practice 571, 572 (2019) (noting, however, that, notwithstanding positive evaluations of CHWs’ work in clinical settings, more research is necessary to gain a full picture); see also Caitlin Allen et al., Strengthening the Effectiveness of State-Level Community Health Worker Initiatives Through Ambulatory Care Partnerships, 38 J. Amb. Care Mgmt. 254, 254 (2015).

See Randall Bobvjerg et al., The Evolution, Expansion, and Effectiveness of Community Health Workers, Urban Institute (December 2013), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/32556/413072-The-Evolution-Expansion-and-Effectiveness-of-Community-Health-Workers.PDF; Jocelyn Carter et al., Implementing community health worker-patient pairings at the time of hospital discharge: A randomized control trial, 74 Contemp. Clin. Trials 32 (2018).

See Michel Ollove, Under Affordable Care Act, Growing Use of 'Community Health Workers,Pew Stateline Article (July 8, 2016), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/07/08/under-affordable-care-act-growing-use-of-community-health-workers.

See Medicaid Coverage of Community Health Worker Services, MACPAC (April 2022), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Medicaid-coverage-of-community-health-worker-services-1.pdf.

See generally Caitlin G. Allen et al., Is Theory Guiding Our Work? A Scoping Review on the Use of Implementation Theories, Frameworks, and Models to Bring Community Health Workers into Health Care Settings, 25 J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 571 (2019).; Julianne Payne et al., Integrating Community Health Workers (CHWs) into Health Care Organizations, 42 J. Community Health 983 (2017).

See Colette Lamothe-Galette Community Health Worker Institute, N.J. Dep’t. of Health, https://www.nj.gov/health/fhs/clgi/.

See generally Nat’l Acads, of Scis., Eng’g, and Med., Communities in action: Pathways to health equity (J.N. Weinstein et al., eds., 2017). See generally Institute of Medicine, supra note 24.

See generally, Brian D. Smedley & Hector F. Meyers, Conceptual and Methodological Challenges for Health Disparities Research and their Policy Implications, 70 J. Soc. Issues 382, 384-86 (2014); see also Daniel E. Dawes, The Political Determinants of Health, 46 J.L. Med. & Ethics 836 (2018).

See generally Institute of Medicine, supra note 24.

See Monica E. Peek, Racism and health: A call to action for health services research, 56 Health Serv. Resch 569, 569 (2021); see also Ruqaiijah Yearby, Structural Racism and Health Disparities: Reconfiguring the Social Determinant of Health Framework to Include the Root Cause, 48 J.L. Med. & Ethics 518 (2020).

See Mantel, supra note 5, at 139-40.

See discussion, supra Part III.

Richard C. Boldt & Eleanor T. Chung, Community Health Workers and Behavioral Health Care, 23 J. Health Care L. & Pol’y 1, 4 (2020).

See discussion, supra Part I.

See Terry Mason et al., Winning Policy Change to Promote Community Health Workers: Lessons From Massachusetts in The Health Reform Era, 101 Am. J. Pub. Health 2211 (2011).

See discussion, supra Part I.

Sarah Torres et al., Improving Health Equity: The Promising Role of Community Health Workers in Canada, 10 Healthcare Policy 73, 76-77 (2014).

Id. at 77.

See id. at 76-77.

See id. at 77.

See Cheryl Garfield & Shreya Kangovi, Integrating Community Health Workers Into Health Care Teams Without Coopting Them, Health Aff. Forefront (May 10, 2019), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190507.746358/full/.

Other solutions, of course could be developed. One is for CHWs to bill as independent contractors perhaps with the use of a billing clearinghouse or other agent. This solution is beyond the scope of this paper.

See Megan Coffinbargar et al., Risks and Benefits to Community Health Worker Certification, Health Aff. (July 7, 2022), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220705.856203/.

See text, supra note 62.

This dichotomy may be read as suggesting that health entities cannot be community-based and responsive. That reading is certainly not intended; for present purposes I mean to juxtapose community-based nonprofits addressing specific community problems such as housing insecurity and food insecurity as contrasted with organizations (including community-based organizations) such as federally qualified health centers that address local needs but through a clinical lens.

Karen LeBan et al., Community health workers at the dawn of a new era, 19 Health Rsch. Pol’y & Sys. 1, 4 (2021).

An excellent special issue of the Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics gathered papers from a 2017 conference of scholars discussing the medicalization of poverty. See Lois Shepherd & Robin Fretwell Wilson, The Medicalization of Poverty, 46 J. L. Med. & Ethics 563 (2018) (describing conference and resulting papers). For an interesting back-and-forth on the related topic of the medicalization of civil rights law, see Craig Konnoth, Medicalization and the New Civil Rights, 72 Stanford L. Rev. 1165 (2020); Allison K. Hoffman, How Medicalization of Civil Rights Could Disappoint, 72 Stanford Law Review Online 165 (2020); Rabia Belt & Doron Dorfman, Reweighing Medical Civil Rights, 72 Stan. L. Rev. Online 176 (2020); Craig Konnoth, Medical Civil Rights as a Site of Activism: A Reply to the Critics, 72 Stan. L. Rev. Online 104 (2020).

See B. Cameron Webb & Dayna Bowen Matthew, Housing: A Case for the Medicalization of Poverty, 46 J.L. Med. & Ethics 588, 588 (2018).

Jacobi, supra note 6.

Id.

See, e.g., Webb & Matthew, supra note 75 at 592-93; Jacobi, supra note 6 at 158-59.

See William M. Sage & Jennifer E. Laurin, If You Would Not Criminalize Poverty, Do Not Medicalize It, 46 J.L. Med. & Ethics 573, 573-74 (2018) (“Count us as skeptical. . . . [W]e urge policymakers to disconnect the relief of poverty from medical care as much as possible—not only to avoid further disadvantaging the poor, but also to encourage investment in unadorned benefits to poorer Americans . . .”).

See Shepherd & Fretwell Wilson, supra note 74 at 563-64.

See Webb & Matthew, supra note 75 at 588.

See generally Helena Hansen et al., Pathologizing Poverty: New forms of Diagnosis, Disability, and Structural Stigma Under Welfare Reform, 103 Soc. Sci. & Med. 76, 76 (2014) (describing the subjective experience of structural stigma imposed by the increasing medicalization of public support for the poor).

See Jacobi, supra note 6 at 158-59.

See Role of Community Health Workers, Nat’l Heart, Lung, and Blood Inst., https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/healthdisp/role-of-community-health-workers.htm (last visited Feb. 3, 2021).

Paula A. Braveman et al., Health Disparities and Health Equity: The Issue is Justice, 101 Am. J. Pub. Health S149 (2011).

See Brandi Leach et al., Primary Care Multidisciplinary Teams in Practice: A Qualitative Study, 18 BMC Fam. Prac. 115 (2017).

See Gunderson et al., Community Health Workers as an Extension of Care Coordination in Primary Care: A Community-Based Cosupervisory Model, 41 J. Ambulatory Care & Mgmt. 333 (2018).

See Malcarney et al., supra at 30.

See e.g. Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein, The Perils and Payoffs of Alternative Payment Models for Community Health Centers, Commonwealth Fund, (January 19, 2022) https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2022/jan/perils-and-payoffs-alternate-payment-models-community-health-centers (describing an alternative payment model by which AltaMed, a large federally qualified health center, receives partial capitation and supplemental payments that allows CHWs to visit to “support patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes.”).

When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton reportedly responded, “Because that’s where the money is.” See Willie Sutton: The colorful character who said he robbed banks “because that’s where the money is” was one of the first fugitives named to the FBI’s Top Ten list, Fed. bureau of Investigation, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/willie-sutton#:~:text=One victim said witnessing one,that’s where the money is.” (last visited Aug. 15, 2023). Similarly, or perhaps only a bit similarly, Medicaid and other health insurers are attractive to those seeking sustainability strategies for CHW work because that’s where the money is.

See Sustainable Strategies, Rural Health Info. Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/community-health-workers/6/strategies (last visited Jan. 3, 2023).

The model described in this part has been used to allow CHWs and the CBOs with which they work to connect with Medicaid managed care organizations directly as well as hospital and primary care practices largely paid by Medicaid. See discussion infra notes 101-103 (describing Ohio, San Antonio and San Diego programs).

See Beth A. Brooks et al., Building a Community Health Worker Program: The Key to Better Care, Better Outcomes, & Lower Costs (2018), https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-10/chw-program-manual-2018-toolkit-final.pdf.

See Agency for Health Rsch. & Quality, Connecting Those at Risk to Care: The Quick Start Guide to Developing Community Care Coordination Pathways (2016), https://www.ahrq.gov/innovations/hub/quickstart-guide.html [hereinafter AHRQ Quick Start Guide].

Id.

Id.

See id.

Id.

Id. at 11-12.

See e.g., The Pathways Community HUB Model, Community Action, Akron-Summit, https://www.ca-akron.org/pathways-community-hub-model (last visited Mar. 6, 2023).

Pathways Community HUB, Grow Healthy Together, https://www.growhealthytogether.com (last visited Nov. 27, 2023).

Community connections create health and wellness, Neighborhood Networks, https://neighborhood-networks.org/ (last visited Nov. 27, 2023)

See Agency for Health Rsch. & Quality, Pathways Community HUB Manual: A Guide to Identify and Address Risk Factors, Reduce Costs, and Improve Outcomes, (2016), https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/innovations/CommunityHubManual.pdf [hereinafter AHRQ Pathways Community HUB Manual]; see AHRQ Quick Start Guide, supra note 94.

See AHRQ Quick Start Guide, supra note 94, at 4.

See AHRQ Pathways Community HUB Manual, supra note 103, at 1.

Id.

Id. at 11-12.

See AHRQ Quick Start Guide, supra note 94 at 34-36.

See AHRQ Quick Start Guide, supra note 94 at 4.

See generally AHRQ Pathways Community HUB Manual, supra note 103.

See id.

See e.g., Allen et al., supra note 48.

See Covert et al., supra note 19 at 322; C3 Progress Report, supra note 18, at 9; Findley et al., supra note 18, at 1983. See generally Jessica Mantel et al., Developing a Health Care Workforce that Supports Team-Based Care Models that Integrate Health and Social Services, 15 St. Louis U. J. Health L. & Pol’y 237 (2022); Mantel, supra note 5.

See Caitlin G. Allen et al., Strategies to Improve the Integration of Community Health Workers into Health Care Teams: “A Little Fish in a Big Pond”, CDC (Sept. 17, 2015), https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2015/15_0199.htm#print.

Cueva et al., Community Health Workers as a Sustainable Health Care Innovation, 9 Elementa Sci. of the Anthropocene 1 (2021).

See Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities, Am. Pub. Health Access (Nov. 10, 2009), https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities.

Mary-Beth Malcarney et al., The Changing Roles of Community Health Workers, 52 Health Serv. Rsch. 360, 367 (2017).

Id. at 363.

Cheryl Garfield & Shreya Kangovi, Integrating Community Health Workers Into Health Care Teams Without Coopting Them, Health Aff. Forefront (May 10, 2019), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190507.746358.

Community Health Workers, Univ. of PA., https://chw.upenn.edu/ (last visited Mar. 4, 2023).

Garfield & Kangovi, supra note 119.

Id.

Id.

Mary-Beth Malcarney et al., Community Health Workers: Health System Integration, Financing Opportunities, and the Evolving Role of the Community Health Worker in a Post-Health Reform Landscape 34-35 (The George Wash. Univ. Health Workforce Rsch. Ctr. 2015).

See discussion, supra Part II.

See Ashley Collinsworth et al., Community Health Workers in Primary Care Practice: Redesigning Health Care Delivery Systems to Extend and Improve Diabetes Care in Underserved Populations, 15 Health Promotion Prac. 51S, 53S (2014).

See discussion, supra Part III.

See discussion, supra Part IV (a).

Id.

See discussion, supra Part III.

See discussion, supra Part IV (b).

Id.