Introduction

In 2011, Lindsay Kamakahi and Justine Levy filed a class-action lawsuit against the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)[1] and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) for violating Section I of the Sherman Antitrust Act.[2] The suit targeted ASRM’s ethical guidelines regarding the appropriate compensation rates for women who choose to sell[3] their eggs to fertility clinics and egg agencies, guidelines which limited compensation to $5,000 in general and $10,000 under special circumstances.[4] Such a pricing cap, Kamakahi and Levy argued, was blatant price-fixing under the Sherman Act,[5] and one that artificially suppressed compensation rates to the detriment of egg donors like themselves.

After four years of litigation, the plaintiffs emerged victorious. The parties reached a settlement agreement under which ASRM would remove the guidelines and refrain from making any recommendations regarding price moving forward.[6] As a result, ASRM’s member clinics would now be allowed to price according to market demands, free from any artificial price caps. Given that the market for human eggs is a thriving one, as well as a core submarket of the larger multibillion-dollar market for fertility services, the plaintiffs likely thought it was only a matter of time before compensation rates rose substantially. But was this a realistic expectation?

In this Article I argue that the removal of the guidelines, while an important step in any effort to encourage full competition in the market for human eggs,[7] was likely limited in terms of practical effect. The market for human eggs is normatively “charged” in a way that other markets—for instance, the market for home title searches—are not. Because the sale of human eggs makes many if not most societal members uncomfortable, many actors in the market frame the transaction as a gift. Women who “donate” are often expected to be motivated not solely by a desire to earn money, but also a desire to “give the gift of life” to a couple in need. Indeed, there is widespread agreement in the market that egg donors, in contrast to other market actors, should not seek to maximize their compensation. This normative agreement has spawned several market practices that likely impede price competition among clinics.[8] While the Kamakahi lawsuit successfully eliminated one of those anticompetitive practices, it left the others untouched.

To support my argument, I draw upon an original dataset of compensation rates from over 500 fertility clinics and egg agencies across the United States. To my knowledge, this is the first and most comprehensive dataset on egg donor compensation in the United States since 2009. I find that, while the average payment to first-time egg donors has risen in the decade following the filing of the Kamakahi lawsuit, most firms are still offering compensation in line with the upper cap of the now defunct guidelines.[9] And this is true even in those regions of the country witnessing the greatest competition among recruitment programs.[10] Further, some fertility clinics have not increased their compensation rate in over ten years, not even to account for inflation.[11]

These results suggest price-fixing lawsuits, acting alone, may be ill-suited to encouraging price competition in markets where price collusion is based not only upon explicit, economic agreements among buyers, but also upon implicit moral agreements as well. Indeed, for those who want to encourage further competition in the market going forward, antitrust law is probably not the appropriate tool for doing so. It is not a violation of the antitrust law for individual firms to share a normative agreement that one should not pay egg donors above a certain amount.[12] And plaintiffs would likely have a very hard time finding evidence of explicit price collusion among fertility clinics.

Instead, I suggest that regulations focused on encouraging transparency within the market are perhaps the most fruitful path forward. States should implement reporting regimes that require clinics not only to report their compensation rates, but also to report the health outcomes and patient experiences of the women they pay to treat. Such information should then be made available to the public, so that prospective donors can make an informed decision about which firm to work with. In the long run, this will incentivize firms not only to compete in terms of compensation, but also to compete in terms of health outcomes. Thus, while the thought of encouraging competition in the market for human eggs might at first strike some readers as undesirable, it could in fact result in much better outcomes for donors, both as sellers and as patients.

This Article is organized in five parts. Part I provides a brief overview of the egg donation process, the ethical debate surrounding compensation, and the events leading up to the Kamakahi lawsuit. Part II details the normative underpinnings of competition in the egg donor market and outlines some of the anticompetitive practices at play within the market. Part III-A details the data collection process and project methodology. Part III-B compares egg donor compensation rates pre– and post–removal of ASRM’s guidelines. I conclude by considering the ways in which policymakers can encourage further competition in this market.

I. The Price of Fertility: Egg Donor Compensation in the United States

Egg donation emerged in the early 1980s as a method for treating female infertility.[13] It involves the transfer of human eggs from a healthy donor for use by another woman who, for whatever reason, is unable to use eggs of her own.[14] Until recently, it was only possible for medical providers to transfer freshly donated eggs into a recipient.[15] This required a donor to synchronize her menstrual cycle with the intended recipient and, once synchronized, to self-administer daily hormonal injections to stimulate egg production.[16] All told, the process of donating fresh eggs might take anywhere from 2–7 months from the time a donor is matched with a recipient to the day of the egg retrieval.[17]

Recent advancements in cryopreservation techniques, however, mean that egg donors now have the ability to donate to egg donor “banks” run by clinics or agencies without any prior matching with a recipient.[18] Although the end of the donation process is the same—a 10–15 minute outpatient surgery during which the provider suctions eggs from the ovaries—a donor who donates frozen eggs is able to cut down on the amount of time involved between being accepted as a donor and making a donation.[19] And the clinic or agency, in turn, can store the resulting eggs for as long as it takes to find an interested buyer.[20]

Importantly, although the use of the word “donation” is ubiquitous within the assisted reproductive market, the vast majority of egg donors in the United States are compensated for their willingness to relinquish their eggs.[21] This has been true since the early years of egg donation, when donors received payments ranging anywhere from $250 to $1,200.[22] Although there is very little systematic data tracking compensation rates over time, it is clear that rates have increased steadily over the past few decades. For instance, the Presbyterian Medical Center in New York paid $250 in 1984, $500 in 1987, $1,500 in 1993, and $2,500 in 1998.[23] By 2009, the average compensation rate for the entire U.S. had risen to $5,890.[24]

The widespread practice of compensating egg donors for their eggs, however, should not be confused with a widespread acceptance of it. Compensation for egg donors—in stark contrast to that of sperm donors[25]—has been the focus of a great deal of debate since egg donation became possible, and that debate continues today.[26] For some, the practice of compensating egg donors is viewed as harmful to society because it encourages individuals to think of human body parts as commodities, as mere property that can be traded without any recognition for the dignity of human life.[27] Such fears are compounded by the fact that some clinics will pay higher fees to women with particular characteristics, such as a certain ethnic group status or religious background.[28] Payments to egg donors also raise fears of exploitation or coercion; if compensation rates are exorbitant, it is theorized, some women may be induced into donating when they would really rather not, or without considering the potential medical risks.[29]

In response to such arguments, proponents of compensation point out that society already routinely commodifies the human experience, with little protest or sense of harm from society members.[30] Ruth Macklin, for instance, notes that “[e]very service in our economy is sold: academics sell their minds; athletes sell their bodies. . . .[I]f a pretty actress can sell her appearance and skill for television, why should a fecund woman be denied the ability to sell her eggs? Why is one more demeaning than the other?”[31] And, as Bonnie Steinbock points out, while we might worry that some women would discount the medical risks of donation because of excessive compensation rates, it also seems unjust to pay women little or nothing for the very real work they do in producing the eggs.[32] Why, that is, would “only egg donors [be] expected to act altruistically, when everyone else involved in egg donation receives payment?”[33]

In 1994, ASRM waded into the compensation debate by taking the stance that reasonable compensation to egg donors (and sperm donors) is ethically permissible, but remained silent as to exactly what compensation amounts might be considered ethically appropriate.[34] ASRM then made its first (and only) attempt to define “reasonable compensation” six years later.[35] Citing a prior study that found sperm donors earned $60 to $75 per hour and that egg donors spend an estimated 56 hours in a medical setting per donation cycle, ASRM calculated that a comparable payment for egg donors would be $3,360 to $4,200 per egg-donation cycle.[36] Recognizing, however, that egg donation is qualitatively different from sperm donation in terms of “time commitment, risk, and discomfort,” the report went on to conclude that egg donors could ethically receive more than $4,200 but cautioned that “sums of $5,000 or more require justification and sums above $10,000 go beyond what is appropriate.”[37] Thus, ASRM essentially put forth a two-tiered pricing cap, with a “soft” lower cap and a “hard” upper cap.

As several observers have pointed out, these guidelines were quite vulnerable to criticism.[38] First, there is no obvious reason why sperm donor rates should be considered an appropriate benchmark for egg donor compensation. Donating sperm and donating eggs entail very different processes, the most obvious being that donating eggs requires surgery while sperm donation does not.[39] Second, ASRM never explained why an extra $1,640 to $800 (the difference between the lower cap of $5,000 and the base calculations of $3,360 and $4,200) accounted for the stark differences between egg and sperm donation. Third, ASRM never explained just what sort of justifications would make a $10,000 payment appropriate, nor why $10,000 was to be considered the absolute limit. The caps were simply presented as reasonable limitations.[40]

Regardless of the arbitrariness of the selected caps, however, the ASRM guidelines had the potential to be of considerable consequence for egg donors in the United States. Over 95% of the assisted reproductive technology (ART) clinics in the nation are members of SART which, as an affiliate of ASRM, adheres to all of its ethical guidelines.[41] This means that nearly all of the fertility clinics in the United States providing egg donor services should have been incentivized to comply with ASRM’s price caps.[42] And while egg donor agencies do not technically fall within the purview of ASRM and SART, in May of 2005, SART sent a letter to independent egg donor agencies informing them that all donor agencies serving SART–member clinics were expected to abide by the ASRM egg donor compensation guidelines.[43] The agencies were asked to sign an abidance agreement and to notify the SART clinics they worked with of their compliance.[44] In return, SART agreed to post the names of compliant agencies (along with the compliant member clinics) on the SART website.[45] The list of compliant agencies was also forwarded to two consumer organizations—RESOLVE and the American Fertility Association (AFA)—to provide information to patient-consumers interested in locating agencies in compliance with the guidelines.[46] In February of 2006, SART sent a follow up letter stating that failure to adhere to the ASRM/SART guidelines would result in removal of the agency from the list of approved programs.[47]

Notably, as the years passed ASRM never re-evaluated its guidelines to determine if its articulated caps remained appropriate, nor did it raise the compensation rate to reflect increases in inflation. Given this, it perhaps was only a matter of time before the guidelines became the target of attack.[48] In 2011, Lindsay Kamakahi and Justine Levy brought a class action suit on behalf of themselves and other egg donors against ASRM and SART.[49] The suit challenged the ASRM–SART guidelines, arguing that they constituted an illegal price–fixing agreement in violation of the Sherman Act of 1890.[50] The guidelines, the plaintiffs argued, worked to artificially suppress the price of donor services to the detriment of donors across the United States. [51]

Although ASRM and SART argued that egg donor compensation is “far removed from the ordinary stuff of antitrust cases” and that Kamakahi and Levy were attempting to “shoehorn legitimate ethical rules . . . into Sherman Act concepts far removed from the professional judgments embodied”[52] in the guidelines, the suit was arguably a strong one. This is because courts have long declared price fixing agreements, i.e., agreements among horizontal competitors to control prices, to be per se illegal under the Sherman Act. As such, these types of arrangements are conclusively presumed illegal without any inquiry into whether competition is actually reduced or whether consumers are actually harmed. And this is true regardless of whether the agreement is to keep prices high or low.[53]

The ethical guidelines, on their face, were a price-fixing agreement. Membership in ASRM and SART was conditioned on fertility clinics’ agreement to abide by the pricing caps outlined in the guidelines.[54] As such, the guidelines easily fell within the per se prohibition. Yet ASRM and SART argued that the context of egg donation was so far removed from society’s normal understanding of commerce and competitive markets as to make the per se rule inapplicable.[55] The court should instead, ASRM and SART argued, analyze the ethical guidelines using the rule of reason, a method of analysis that requires the court to determine whether the procompetitive effects of the targeted conduct outweighs any anticompetitive effects.[56] Under the rule of reason analysis, antitrust plaintiffs must demonstrate that a particular contract or combination is in fact unreasonable and anticompetitive before it will be found unlawful.[57] Noting that the per se rule has been reserved only for those practices with which the courts have had “considerable experience”[58] and “whose inherent economic character allows judges ‘to predict with confidence that the rule of reason will condemn’” them in essentially all of their manifestations,[59] ASRM and SART argued that the professional setting of the ethics guidelines was reason enough for the court to substitute a per se analysis with the rule of reason.

But as other scholars have noted, the ethical guidelines were problematic even from a rule of reason perspective,[60] and the Supreme Court’s previous rulings regarding professional associations’ use of ethical guidelines to curb competition among professionals did not bode well for ASRM and SART. Although the Court had previously suggested that it “would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities [and]to apply to the professions antitrust concepts which originated in other areas,”[61] the Court had also struck down as illegal all the professional ethics guidelines to come before it under the antitrust laws. Perhaps most importantly, the Court had twice struck down professional ethics guidelines attempting to fix prices among professionals, first in Goldfarb v. Virginia (a minimum fee schedule set by the Virginia Bar Association) and then again in Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (a maximum fee schedule set by medical providers).[62] ASRM, therefore, faced an uphill battle in defending its guidelines.

Ultimately, after four years of litigation, the egg-donor plaintiffs prevailed: ASRM agreed to remove its pricing caps from its ethical guidelines as part of a settlement agreement.[63] ASRM also agreed, moving forward, to refrain from recommending or listing any dollar amounts or ranges regarding egg donor compensation through any of its boards, working groups, or committees and to refrain from conditioning membership on agreements to adhere to any type of dollar limits for compensation rates.[64] Each of the individual plaintiffs also received $5,000 in damages and their attorneys received $1.5 million in fees.[65]

On its face, the settlement agreement was a rousing success for the plaintiffs. With the removal of the guidelines, donor compensation rates would presumably be free to rise as the market dictated. And the plaintiffs certainly hoped that the rise in price would be substantial. In the next section, however, I suggest that pricing consequences of the settlement may have been less momentous than they appeared at first glance. This is because ASRM’s pricing guidelines did not exist in a vacuum. Instead, they were complemented by other anticompetitive market practices unique to the market for human donor eggs.

II. The Moral Trappings of Competition in the Egg Donor Market

A priori, should we expect the Kamakahi settlement and the removal of the pricing guidelines to have had a substantial impact on the price of human eggs? Kamakahi and Levy certainly must have hoped so; they brought suit because they believed the guidelines were artificially suppressing compensation rates and hoped that their removal would enable compensation to rise.[66] Such hopes were certainly not unreasonable. ASRM’s ethics guidelines were, on their face, a naked price-fixing agreement among competitors in the market for human eggs. And similar lawsuits targeting price-fixing had been successful in other markets. For instance, in the leadup to the Supreme Court’s consideration of Goldfarb v. Virginia, a price-fixing lawsuit targeting the Virginia Bar Association’s minimum fee-schedule for home title searches, the prices for title searches fell by 50 percent or more as lawyers began disregarding the fee-schedule in anticipation of its demise.[67]

It is possible, however, that the removal of the guidelines did not have a dramatic impact on compensation rates in the United States.[68] The price–fixing agreements at the center of Goldfarb and Kamakahi were very different. The former concerned a market product associated with few, if any, moral overtones.[69] The latter, in contrast, concerned a market product deeply infused with moral implications.[70] This is significant because one way of conceptualizing ASRM’s ethical guidelines is to view it as an explicit economic agreement sitting atop a set of already existing moral agreements concerning both the ethical pricing of donated eggs and the ways in which buyers and sellers should approach the transaction. While a price–fixing lawsuit can target explicit pricing agreements among market competitors, it cannot target moral agreements about just what constitutes proper market behavior. And moral agreements about proper market behavior can constrain competition just as effectively, if not more effectively, as do the more run-of-the-mill collusive agreements.

Previous research has shown that the market for human eggs exists in an “uncertain place between the world of gift and the world of [the] market.”[71] Because the sale of human eggs makes many if not most societal members uncomfortable, the transaction is regularly framed as a gift. Indeed, Kimberly Krawiec has suggested that the use of “gift discourse” may be what allows the market in human eggs to thrive despite society’s discomfort with it.[72] In practical terms, what this means is that while it is generally accepted that donors will be compensated, donors are still expected to be motivated by a large dose of altruism. In contrast to other markets, there is a widespread agreement that egg donors are not—and should not behave like—ordinary market participants seeking to maximize their compensation above all else.[73]

This expectation of altruism manifests in a variety of market behaviors. First, as one former egg donor explained, most potential donors will at some point “encounter discussions in which they have to prove that they are not entirely out to get paid:”[74] women who show “too much” interest in compensation, or who are seen as attempting to “make a career” out of egg donation are less likely to be accepted as a donor. Indeed, some firms state explicitly on their website that they will not work with donors who are primarily motivated by financial gain.[75] Second, accounts from egg donors indicate that some agencies may attempt to pressure women to accept a lower compensation rate by suggesting that donors who insist on high compensation are harming infertile couples. One donor reported that after having been accepted into a donor program she experienced pressure from her agency to lower her requested compensation rate. When she “stuck to [her] guns about her requested compensation,” the agency told her, “[w]e’re not in the business of trying to just take money from parents.”[76] Similarly, one firm’s website encourages donors to consider “the financial difficulty” that a high compensation request might impose on “couples who [] so desperately want a child,” while another suggests that repeat donors (who are told they can request higher compensation) “be conscientious of the financial burden for intended parents while considering [their] requested compensation.”[77]

The normatively “charged” nature of the donor egg market also likely accounts for the fact that a small but significant number of firms do not provide transparent pricing information to potential donors.[78] Presumably, staff members at these organizations feel that a properly motivated donor does not need this information before deciding whether to undergo the effort of submitting an application (an application which typically requires reporting multiple generations of family medical history and providing a detailed autobiography). Instead, these firms explicitly solicit potential egg donors on their websites but provide no pricing information to interested women beyond acknowledging that compensation will be provided. Potential donors are instructed to reach out for further information or to begin the application process without pricing information.[79]

Notably, during the data collection stage of this project, it became apparent that many of these firms are reluctant to provide information regarding compensation even when a potential donor follows up for more information.[80] When I reached out, stating that I was interested in an egg donation program and would like to know what the starting rate was for a first-time donor, I was often placed on long holds or told a staff member would call me back with further information. Many times, the follow up call never came.[81] Consider also my interaction with one clinic: in response to an email that inquired about both the eligibility requirements for egg donors and the basic compensation rate, a staff member at one clinic answered only the eligibility question, made no reference to compensation, and asked if I would like to begin the screening process. When I politely followed up with a thank you and a second inquiry as to the compensation rate, I received no response. It seemed I had been “screened out” as too interested in the money.

These market practices are clearly anticompetitive. By refusing to provide transparent pricing information to interested donors, firms prevent potential donors from easily comparing compensation rates across clinics in order to maximize their potential reward.[82] This means that some women will find themselves settling for a lower rate than they might have otherwise, either because they do not realize they are being underpaid or because, by the time they realize it, they are already in the midst of the donation process. And some women will only realize they could have received a larger payment after they have already donated. The practice of pressuring potential donors to accept lower compensation, of course, also helps maintain a lower average compensation rate than we might otherwise see.

Yet, while these market practices are clearly anticompetitive, antitrust law has very little to say about them, at least as traditionally conceptualized. Certainly, the Kamakahi lawsuit, acting alone, could not target market practices like these. It is not a violation of the antitrust laws for an individual—or an individual firm—to take the position that there is an ethical limit to the amount of compensation they are willing to provide to a woman selling her eggs. Indeed, the Kamakahi court’s settlement order made clear that individual members of SART and ASRM, including members of the ethics committee, have the right to publicly or privately express their personal opinion on the amount of compensation that can or should be paid by any clinic or donor agency for donor services.[83] Fertility clinics and agencies only err into forbidden territory when they attempt to form explicit agreements with their competitors or condition membership in a professional association on pricing behavior.

This is not to say, however, that we should necessarily expect the removal of the guidelines to have been inconsequential. Although the egg donor market is infused with a shared set of moral assumptions about the proper way in which to buy and sell human eggs, it is still a market. And a multibillion dollar one at that. Making money is the name of the game—in addition to helping individuals and couples form families. But the point here is that the price-fixing lawsuit targeted only one anticompetitive aspect of the egg donor market, while leaving in place the more amorphous set of beliefs that gave rise to the guidelines in the first place. This in turn may have limited the practical effect of the guidelines’ removal on compensation rates.

III. Egg Donor Compensation in the United States Following Kamakahi

In the years following the Kamakahi settlement, anecdotal news reports have suggested that egg donation can now be a lucrative career for the women who choose to donate.[84] But these claims are based on interviews with very few donors from a small selection of fertility clinics and egg donor agencies.[85] As of yet, there has been no systematic examination of donor compensation in the post-Kamakahi world. This section draws on an original dataset of donor compensation rates from over 500 fertility clinics and egg agencies to provide a comprehensive look at egg donor compensation rates in the United States ten years after the Kamakahi lawsuit was filed. I find that prices have in fact risen in the decade following the Kamakahi lawsuit. But my results also show that the majority of firms are still offering compensation in line with the $10,000 cap of the old guidelines. If the goal of the Kamakahi lawsuit was to see prices rise above that cap, then that goal has clearly not been met.

A. Data and Measurement

Determining whether prices have risen in the ten years following Kamakahi requires a comparison of pre– and post–Kamakahi prices. [86] For pre–Kamakahi prices, I rely on Kathryn Johnson’s 2009–2010 dataset;[87] it is the most comprehensive dataset of pre–Kamakahi donor compensation rates available. Johnson’s data is particularly helpful because her data collection ended only a year prior to the filing of the Kamakahi lawsuit and therefore provides a very timely snapshot of the market for donor eggs at the time in which the plaintiffs were alleging price suppression. Using a combination of clinic lists from the CDC, ASRM, and national fertility organizations, Johnson was able to collect donor compensation data for 284 clinics and donor agencies across the United States in 2009 and 2010.

For 2020–2021 pricing data, I rely on my own original dataset of donor compensation rates collected between December of 2020 and March 2021.[88] Following Johnson, I used the most recent list of clinics (2018) from the CDC’s website as a starting point for my sample. I then supplemented that list in two ways. First, I conducted Google searches for egg donor recruitment programs in order to locate donor clinics and agencies that might have entered into business since the CDC list was published. Second, I compared my list of clinics to the list compiled by Johnson and added to my own list clinics she had located that were not listed by the CDC.

Once I had my sample list, I searched for each clinic or egg agency online. Nearly all organizations had an online presence, but it was not clear from every website whether the clinic had an egg donor program. For instance, some clinic websites indicate that they operate a donor recruitment program, some indicate that they contract out with a donor egg agency, and others list donor eggs as one of their available services but do not indicate whether they are actively recruiting donors or whether they contract with a donor agency.[89] Many of the clinics that explicitly advertised their donor recruitment program on their websites provided pricing information, but a significant number of them did not. For those clinics and agencies that did list compensation rates, I simply recorded the price (or price range) as listed.[90] I then called the remaining clinics on my list (both those that clearly had an egg donor program but no pricing information and those whose websites suggested an egg donor program might exist, but which provided no pricing information). When speaking to a representative, I asked what the clinic’s compensation rate was for a first-time egg donor.[91]

In total, I was able to collect compensation rates for a total of 506 discrete clinics and agencies.[92] Of those, 156 clinics have both 2009–2010 and 2020–2021 price points. The low match rate reflects the fact that during the ten years between Johnson’s data collection and my own, a considerable number of clinics either closed or merged with another medical organization.

Johnson’s prior work demonstrated that several factors influence the rate at which egg donors are compensated: organizational form, consumer demand, donor supply, market competition, and market structure.[93] I include the same independent variables in my updated dataset (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics), operationalized in the same manner as in Johnson’s dataset.[94] Doing so allows me to compare the relative strength of these predictors before and after the guidelines were removed. This in turn allows me to get a sense of whether the removal of the guidelines had an impact on pricing.

Organizational form distinguishes between clinics and egg donor agencies,[95] with agencies coded as 1 and clinics as 0. Consumer demand was assessed with three measures using data from the 2000 (for the 2009–2010 data) and the 2010 (for the 2020–2021 data) censuses: relative income of the local population, the proportion of highly educated women in the local population, and total population.[96] Both datasets used census places as the unit of measurement.[97] Relative income was calculated by taking the ratio of the median census place income relative to the median state income in order to standardize across states. The proportion of highly educated women was created by summing the numbers of women over twenty-five with a master’s or professional degree, or PhD, in a given census place and dividing by the total female population over twenty-five. Total population was logged after preliminary analyses (in both years) showed a highly skewed distribution.

Donor supply was indicated by the number of four-year colleges or universities within a five-mile radius from the organization. Although not a perfect measure of supply, college campuses—and certainly women of college age—are key recruitment grounds for egg donor programs.[98] The variable was created (for both years) using the College Navigator zipcode searches from the National Center for Education Statistics website.[99] A five-mile radius was chosen because it was the minimal distance available for searching and because we might assume that many students would be unwilling to invest considerable travel time into the donation process.

Market structure was measured by four separate variables: the degree of local market competition, whether an organization was in a mediated medical market (that is, whether the state requires insurance companies to cover the costs of infertility treatments), whether an organization was in the northeast, and whether an organization was in the west.[100] To measure competition, each organization was geocoded, and a distance matrix was computed.[101] Count variables were then created for the number of clinics and agencies within a 20–mile radius of each organization. Dummy variables were created for no competition (no organization within 20 miles) and high competition (11 or more organizations within 20 miles).

B. Analysis

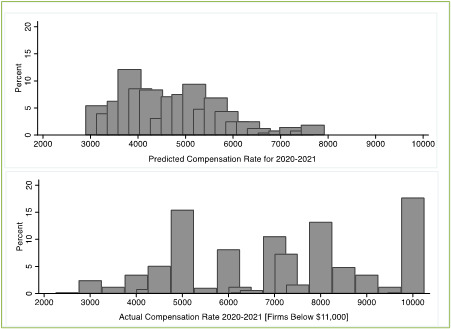

Have egg donor compensation rates risen in the decade since the removal of the guidelines? Consider Figure 1 first. Figure 1 compares the distribution of donor compensation across the United States in 2009–2010 to that of 2020–2021.

What is immediately clear is that the distribution shifted rightward over the past decade. In 2009–2010, when the guidelines were in full effect, the average compensation rate for a first-time donor was $5,280. In fact, the majority of clinics and agencies were offering prices at $5,000 or below.[102] Firms tended to cluster at certain price points, with 50% of firms offering either $3,000, $4,000, or $5,000 as the starting compensation rate.[103] Notably, a full 26% of firms hovered right at $5,000, the “soft” cap under the guidelines, which suggests that $5,000 was operating as a focal point for price setting. At the same time, while about 32% of firms offered rates higher than $5,000, no firm in the dataset offered a compensation rate above the “hard” cap of $10,000.[104]

Fast forward to 2020–2021 and the landscape has changed. The average payment for a first-time donor has increased from $5,280 to $7,292 ($6,044 in 2009 inflation adjusted dollars).[105] While the majority of clinics offered prices at $5,000 or below in 2009–2010, only 28% of firms offered compensation rates of $5,000 or lower in 2020–2021. And whereas clinics clustered at $3,000, $4,000, and $5,000 in 2009-2010, clinics clustered at $5,000, $7,000, $8,000, and $10,000 in 2020–2021. We also see that while only 4 (1.4%) clinics and agencies offered $10,000 for a first-time donation in 2009–2010—and none offered more than $10,000—by 2020–2021, close to 90 clinics and agencies (17.23%) reported first-time payments of $10,000. Another 13 (2.58%) clinics and agencies have moved past the “hard” cap of $10,000 to offer maximum amounts ranging from $12,000 all the way up to $25,000.

Is this increase due to the removal of the guidelines? While the data here cannot prove causation, I perform a few analyses which, when taken together, shed some light on the lawsuit’s impact on the market. First, I examine what factors helped explain donor compensation prior to the removal of the guidelines. I do this by estimating a regression predicting 2009–2010 prices, controlling for organizational form (agency), consumer demand (relative income, proportion of educated women, total population), supply (nearby colleges), and market characteristics (high competition, no competition, insurance mandate, and regions). The results are presented in Table 2.[106] We see that donor compensation rates are higher in locations with a greater number of nearby colleges, in locations experiencing greater competition, in states that require insurance companies to cover the costs of infertility treatments, and in the northeast. Donor compensation rates are lower among clinics and agencies that had no competitor within a 20-mile radius.

I use the regression coefficients from this model to predict what donor compensation rates might look like in 2020–2021 if the guidelines were still in place, while also accounting for observable changes in the market. That is, I use the coefficients from my 2009–2010 model and, using the 2020–2021 values for each of my control variables, generate a predicted 2020–2021 compensation rate for each firm in my own original dataset. I then compare these predicted compensation rates to the actual 2020–2021 compensation rates. If the predicted values matched the actual values, this would suggest that the observable changes in the market fully account for the rise in compensation between 2009–2010 and 2020–2021. This would in turn suggest that the removal of the guidelines was inconsequential. If, however, the change in market demand, donor supply, and the other pricing determinants only partially account for changes in price (i.e., the predicted values do not match the actual 2020 values), then the “unexplained” change might be due to the removal of the guidelines.

Figure 2 compares the predicted 2020–2021 prices to the actual 2020–2021 prices.[107] The distribution of predicted price points shows a price distribution that is very similar to the price distribution of 2009–2010.[108] That is, after accounting for changes in supply, demand, and other relevant determinants over the past ten years, the model still predicts a 2020–2021 pricing “landscape” that looks fairly similar to that of 2009–2010.[109] Based on my control variables, we would not have expected prices to move between 2009–2010 and 2020–2021. But, of course, we know that prices did change. As discussed above, we have seen an increase in the average compensation rate for an egg donor in the United States since 2009–2010. This means that the changes in the market environment are only partially accounting for the increase in compensation rates over the past ten years. Some other factor—or factors—has caused prices to rise.

An obvious explanation for the unexplained rise in prices is, of course, that the guidelines were suppressing the price for donor eggs and that their removal opened the doors to more competitive pricing. This explanation finds support in Table 3. There I present the results of regression models estimating prices in both 2009–2010 and 2020–2021. The coefficients for both High Competition and No Competition for the 2020–2021 model are double those of the 2009–2010 model. This suggests that these competition measures became a more significant determinant of prices between these two time periods. And, again, an obvious explanation for why this would be so is the removal of the guidelines. The results therefore suggest (but do not prove) that the removal of the guidelines allowed donor compensation to increase.

However, even if the removal of the guidelines was the main driver behind this increase in compensation rates, there are two important caveats. First, the increase in compensation rates is arguably not substantial. In 2009–2010, the average payment to a first-time donor was $5,280.[110] In 2020–2021, that number was $7,292 ($6,044 in 2009 inflation adjusted dollars). This is a raw increase of only ~$2,000. When we account for inflation, the increase is even smaller: only $764.[111] Consider also Table 4, which focuses on those clinics in my sample for which I can compare 2009–2010 and 2020–2021 prices.

We see that 21% of firms did not increase their compensation rate at all since 2009–2010. Assisted Fertility in Jacksonville, FL, for example, offered $3000 in 2009–2010 and continues to do so in 2020–2021. Similarly, the Emory Reproductive Center continues to offer the same rate ($6,000) now that it did in 2009-2010. And this is true even though the Atlanta area is home to eight other egg donor programs, all of which offer higher payment amounts. Second, even though we saw a clear increase in price over the past decade, most firms—94%—are still offering compensation rates within the old guideline range. This is true even in the states experiencing the greatest competition among firms. Figure 3, for instance, compares the price distribution among six of the states with the greatest number of fertility clinics and egg agencies. Only three of those states—California, New York, and Texas—feature clinics and agencies offering compensation above $10,000. Furthermore, there is an important qualification when it comes to those firms offering more than $10,000. Every single one of the firms offers a compensation range, rather than a flat fee. For instance, Circle Surrogacy (with locations in California, New York, and Massachusetts) informs donors that they can make between $9,000 and $15,000, while the San Diego Fertility Center (with locations in New York and California) advertises rates between $5,000 and $15,000.

My data is unable to tell us what the average donor at either program is actually earning, but we might suspect that many potential donors apply to these programs hoping to secure payment at the high end of the range, only to be offered a lower amount. After all, donors are not in a particularly strong bargaining position when seeking acceptance into a donor program. As I explained in Part III, potential donors often have to convince program recruiters that they are not unduly motivated by the prospect of compensation. It is difficult to argue for a higher compensation rate while also giving off an air of altruism. Further, some women may feel uncomfortable advocating for a higher price even without pressure on the part of the recruiters. This could be due to the contested nature of egg donation, but it could also be a result of larger forces of socialization. Some studies have suggested that women are less likely to negotiate for a higher wage compared to men, for instance.[112] Offering a compensation range, therefore, might allow firms to appear to be offering above market compensation while in reality they pay donors a lower rate on average.

Finally, it is worth noting that while the majority of firms have stayed within the guidelines, we do see a fair number of firms hovering right at the $10,000 price point. In Figure 2, for instance, we can see that close to 20% of firms are offering a first-time rate of $10,000.[113] Many of these firms are located in California and New York, two of the most competitive areas when it comes to egg donation. Given the number of firms in these states, it is a bit surprising that more are not offering prices above $10,000. Why not go above that amount by even just $1,000? One possible answer is that the market hasn’t demanded such an increase; perhaps the natural market price for donor eggs is $10,000 (or lower). Another explanation, however, is that the guidelines were “sticky” in a way that the Kamakahi plaintiffs may not have anticipated. While it is clear that moral assumptions about the proper price of “donated” eggs preceded the guidelines (indeed, they gave rise to them), the guidelines may have provided explicit pricing focal points to firms operating in the egg donor market. There may now be a sense that $10,000 is the “true” ethical cap for egg donation, such that few firms are willing to go beyond that amount even now. After all, the guidelines were passed by the preeminent professional organization within the assisted reproduction market, and they were also in place for over a decade.

Conclusion: Competition as a Means of Protecting Egg Donors

Although donor compensation rates rose during the ten years following the filing of the Kamakahi lawsuit, I show that the majority of firms continue to offer compensation rates that comply with the now defunct guidelines. This is true even in the most competitive regions of the country. While it is possible that current pricing decisions are the result of unconstrained market forces,[114] previous research—and my own data collection experience—suggests that the market for human eggs is characterized by anticompetitive practices that work to suppress compensation rates.[115] If one’s goal is to ensure that egg donors are paid a competitive price, there is more work to do.

The obvious question, then, is what form that “work” should take.[116] Although the Kamakahi lawsuit may have allowed competition to increase to some degree, antitrust law in general seems an ill–fitting tool for encouraging further competition. As noted earlier, it is not a violation of the antitrust laws for an individual clinic or egg agency to take the stance that paying more than a certain amount for human eggs is unethical or exploitative.[117] Similarly, the fact that many firms are operating under a shared normative agreement does not mean they are violating the Sherman Act.[118] At the very least, proving a violation would be extremely difficult because plaintiffs would need to be able to show some evidence of an economic agreement among firms—not simply a shared sense that payments above, say, $10,000, go too far.

In contrast, regulations aimed at promoting pricing transparency could very well have a positive impact on competition within the market for eggs. During the data collection process for this Article, it became apparent that many firms in this market do not engage in pricing transparency. About 17% of the firms in my sample did not post their compensation rates in their recruiting materials or on their websites. And there were other firms that simply refused to tell me what their compensation rates were, even after I reached out for more information. This means that prospective donors who are considering whether and where to sell may be operating without full information on prices, thereby increasing their search costs in finding the recruitment program where they can maximize their earnings. It also means that some clinics may be securing donors at a lower rate than they might otherwise, because donors do not realize they are being paid a below-market price. This translates to lost wages for donors.

State and federal policy makers have already enacted price transparency laws in the healthcare sector aimed at giving healthcare consumers the information they need to make informed choices.[119] Similar efforts could take place with respect to the market for human eggs. One simple initiative would be to require donor recruitment programs to publish their compensation rates in their recruitment materials and on their websites. But policy makers could also do more to help donors make an informed decision. We might consider, for instance, state-level policies that require clinics not only to post their pricing schemes on their websites and in their recruiting materials, but also to report their prices to the state health department.[120] The state health department, in turn, could compile an annual report of clinic pricing schemes within the state and publish that information on its own website. This would provide prospective donors with the ability to easily compare pricing schemes across all the clinics in a particular state. Presumably, those firms that are currently offering very low rates (below $5,000) would be forced to raise their prices because donors would choose to work with firms offering a more competitive rate.

Yet pricing transparency is not the only type of transparency we should care about if we want to ensure that donors are not underpaid for the service they are providing. The price a donor may be willing to accept in return for undergoing unnecessary medical interventions is presumably dependent upon the type of care she expects to receive during the process and whether she is confident her medical provider is appropriately minimizing the risks involved in her treatment. Although most side effects from the treatment are minor (weight gain, headaches, mood swings), some donors develop ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome (OHSS) as a result of the hormonal medicines used to stimulate their egg production.[121] While a mild case of OHSS can result in abdominal bloating and pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, more serious cases can result in blood clots, kidney failure, stroke, ruptured ovaries and, very rarely, death.[122]

Importantly, the structure of the egg donation process arguably increases the chances that some donors will receive substandard medical care and/or experience OHSS. As several observers have pointed out, fertility clinics and egg agencies face an unavoidable conflict of interest between serving the couples who seek to use donor eggs and serving the women who are willing to provide them (for a price or for free):

The best interests of the [egg donor] demands that the side effects and risks associated with ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval be minimized and requires the physician not to focus on maximizing the production of eggs. To do so, the physician may need to reduce the [egg donor’s] stimulation drugs, to retrieve the eggs before the “maximum” target has been reached, or to cancel the [egg donor’s] cycle if the [egg donor] is at risk of suffering OHSS or other complications. In contrast, the best interests of the recipient require the physician to take steps to maximize the chances of her achieving a pregnancy. To do so, the physician will strive to harvest the greatest number of eggs from the [egg donor].[123]

In addition, because clinics and agencies do not condition donor’s payment on the number of eggs they produce,[124] there may be a similar incentive to harvest as many eggs as possible to get the “best bang for the buck.” And that buck includes not only the donor’s fee, but also the cost of the medications used to stimulate egg production.[125]

This is not to say that every physician operating in the egg donor market is providing subpar medical care in an effort to maximize his or her bottom line. Presumably, the majority of physicians operating in this space are dedicated to providing the best medical care to both their paying patients and the patients they themselves are paying to treat. But if we were willing to simply rely on the good faith of doctors, we would not have medical malpractice laws or licensing requirements.[126] And some physicians are simply better, or more experienced, than others. These physicians may be better able to anticipate the right amount of hormonal medication any given donor needs, while other physicians, although operating in good faith, have a less than stellar track record.

Thus, because prospective egg donors are not only prospective sellers, but also prospective patients, they require full information regarding both the wage they will earn and the quality of medical care they will receive. A donor might, for instance, choose to work with a firm that offers only $7,000 rather than a firm that offers $10,000 because the former firm has a much better record with respect to health outcomes. Similarly, a prospective donor living in a city with two clinics offering the same compensation rate will want to know if one of those firms offers a higher level of medical care. Perhaps 10% of the women who have ever donated at clinic A have suffered from OHSS, while only 5% have done so at clinic B. For the same price, Clinic B is clearly the better choice. And if clinic A wants to stay in business, it will need to demonstrate to prospective donors that it is in fact capable of providing high-level care on par with that provided by Clinic B.[127]

Unfortunately, this sort of price-quality comparison is infeasible in the current market. As noted previously, almost 20% of firms are not transparent about their prices, and very few firms, if any, are transparent about the quality of medical care being provided.[128] Programs do provide testimonials from prior egg donors on their website, but such testimonials are almost always glowing reports of the donation process, and often focused on the emotional benefits that the donor received.[129] There is little, if any, discussion about the health experience of donors. I have certainly never come across a clinic that informs donors of the number of previous donors who have suffered OHSS at their clinic.[130]

Thus, policymakers should require firms not only to publish their compensation rates in their recruitment materials and on their websites, but also to publish information concerning the number of adverse health events suffered by donors in their program and the type of adverse health events suffered. And just like with pricing, policymakers should consider requiring firms to also report this information to the appropriate state health department or agency, which would then compile the information for public dissemination. Prospective egg donors in the state would then have easy access to comprehensive information not only on pricing, but also health outcomes. Armed with this information, prospective egg donors could make an informed choice about whether and with whom to donate. In the long run, firms would be incentivized not only to compete in terms of compensation rates, but also in terms of health outcomes. This would undoubtedly be a win-win for egg donors.

Am. Soc’y For Reprod. Med., https://www.asrm.org/about-us/mission-statement/ (last visited Sept. 9, 2022). ASRM is a non-profit, multidisciplinary organization dedicated to the advancement of the science and practice of reproductive medicine. Periodically, ASRM reviews and publishes updated guidelines, guidance documents, and committee opinions to define the minimum standards for assisted reproductive technology (ART) programs. SART is an affiliate of ASRM and is the primary organization of professionals dedicated to the practice of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the United States. Id.

Lindsay Kamakahi v. Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Consolidated Amended Class Action Complaint., no. 3:11-CV-1781 U.S. Dist. Ct. (N.D. Cal. Apr. 12, 2012) [hereinafter Complaint] Kamakahi filed her original complaint in Apr. of 2011, while Levy filed in September of 2011. The two cases were consolidated in 2012. Id.

Although the common term is “egg donation,” I use “sell” here and elsewhere intentionally for emphasis. As will be discussed further in Part III, although actors in the market for human eggs characterize the sale of human eggs as egg donation, women are in fact selling their eggs to fertility clinics and egg agencies. However, at times I will use the terms “donor,” “donation,” and “egg donation” because they are now so ubiquitous it can be more confusing than not to avoid them.

See Ethics Comm. of the Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Financial Incentives in Recruitment of Oocyte Donors, 74 Fertility & Sterility 216, 219 (2000) [hereinafter Ethics Comm. 2000].

Under the Sherman Act of 1890, “[e]very contract. . .or conspiracy. . .in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States. . .is declared to be illegal.” See 15 U.S.C. § 1.

See Lindsay Kamakahi v. Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Final Order and Judgment, no. 3:11-CV-1781 U.S. Dist. Ct. at *1, *2 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 26, 2016) [hereinafter Final Order].

This Article does not take a stance on whether there should be a market for human eggs. The scholarly debate over the ethics of egg donation is an extensive one, and one in which numerous other scholars have contributed thoughtful and important insights, on both sides of the debate. For my purposes, I accept that regardless of whether one thinks there should be a thriving market for human eggs in the United States, the reality is that such a market exists. As such, the more interesting question now is whether and how competition can be encouraged in this market.

See discussion infra Part II.

See infra Figure 1.

See infra Table 2.

See infra Table 4.

The Sherman Act prohibits certain types of economic agreements, not shared normative beliefs. See 15 U.S.C. § 1.

In 1987, the Cleveland Clinic became the first fertility clinic in the country to match anonymous donors with infertile couples and to compensate the donors. Aaron D. Levine, Self-Regulation, Compensation, and the Ethical Recruitment of Oocyte Donors, 40 Hastings Ctr. Rep. 25, 25 (2010).

Such reasons no longer always implicate infertility. Gestational surrogacy has become an increasingly popular family building tool for LGBT couples who cannot procreate without assistance. A gestational surrogate does not contribute her own eggs to the pregnancy, and so by definition is always receiving donor eggs—either from an anonymous donor, a known donor, or the intended mother herself.

Various oocyte preservation techniques had been developed by the early 1980s, but the success rates for ART fertilization, pregnancy, and live births were much higher using freshly donated eggs. Catherine Waldby, The Oocyte Economy: The Changing Meaning of Human Eggs 122 (2019). More recently, studies have shown much better success rates using vitrification (cryopreservation) methods, with some trials finding no difference in success rates between fresh donor cycles and those using vitrification. Ana Cobo et al., Use of Cryo-Banked Oocytes in an Ovum Donation Programme: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial 25 Hum. Reprod. 2239, 2242-43 (2010).

Waldby, supra note 15, at 126.

See e.g., How Long Does the Egg Donation Process Take?, Bright Expectations (May 22, 2018), https://www.brightexpectationsagency.com/blog/how-long-egg-donation-process/ (stating the process usually takes 2-3 months); Egg Donation Clinic in Virginia, New Hope Ctr. for Reprod. Med., https://www.thenewhopecenter.com/egg-donation-clinic (stating that the donation process can take three months or more) (last visited Aug. 2021); Become an Egg Donor, Utah Fertility Ctr., https://www.utahfertility.com/treatmentivf/third-party-reproduction/become-an-egg-donor/ (suggesting a timeline of 4-7 months) (last visited Aug. 2021).

In 2012, both the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and ASRM announced that oocyte vitrification is sufficiently advanced to no longer be regarded as experimental. These announcements were seen as somewhat of a “tipping point” by staff in the fertility business in terms of encouraging patients to view egg freezing as safe and in spurring the formation of egg banks. See Waldby, supra note 15, at 124.

The webpage for Arizona Reproductive Medicine Specialists suggests that donors can donate and receive compensation within two weeks of their application being approved. Become an Egg Donor, Ariz. Fertility, https://arizonafertility.com/egg-donation/become-egg-donor/ (last visited Aug. 2021). FairFax Eggbank states that the donation process takes about three weeks. How Long Does it Take to Donate Eggs?, FairFax Eggbank, https://www.fairfaxeggbank.com/blog/how-long-does-it-take-to-donate-eggs/#:~:text=In all%2C the egg donation,the process takes on average (last visited Aug. 2021).

See Waldby, supra note 15, at 131.

Daniel Shapiro, Payment to Egg Donors is the Best Way to Ensure Supply Meets Demand, 53 Obstetrics & Gynecology 73, 81 (2018) (finding that in jurisdictions where compensation is prohibited there is no anonymous egg donation).

See Bonnie Steinbock, Payment for Egg Donation and Surrogacy, 71 Mount Sinai J. Med. 255, 259 (2004); Aaron D. Levine, supra note 13, at 25.

Gina Kolata, Price of Donor Eggs Soars, Setting Off a Debate on Ethics, N.Y. Times (Feb. 25, 1998), https://www.nytimes.com/1998/02/25/us/price-of-donor-eggs-soars-setting-off-a-debate-on-ethics.html.

Katherine M. Johnson, The Price of an Egg: Oocyte Donor Compensation in the U.S. Fertility Industry, 36 New Genetics & Soc’y 354, 363 (2017).

Indeed, there has been little, if any debate, over the propriety of compensating men for their sperm. Instead, observers have focused on sperm donor’s legal obligations to their genetic children or, more recently, the possibility that some donors are unknowingly fathering very large numbers of children. In the early years of sperm donation, for instance, observers worried that that if sperm donors were not protected from paternity suits the sperm supply would be compromised. Observers believed men would be unwilling to donate if they might later be tagged as a legal parent. States therefore passed artificial insemination statutes to ensure that “this procreative gift would be separated from fatherhood by clarifying the right of the donor to be absent from parental duties.” Anna Kaminski, Rocking the Cradle, Rocking the Boat: Surrogate Motherhood Legislation in California, 20 (1988) (M.S. thesis, University of California, Berkeley) (eScholarship). More recently, commentators have focused on clinics’ failure to limit the number of children born to a single donor. See, e.g., Arianna Eunjung Cha, 44 Siblings and Counting, Wash. Post (Sept. 12, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/health/44-donor-siblings-and-counting/; Jacqueline Mroz, The Serial Sperm Donor: One Man, Hundreds of Children and a Burning Question: Why?, Irish Times (Feb. 8, 2021), https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/the-serial-sperm-donor-one-man-hundreds-of-children-and-a-burning-question-why-1.4476178. There has been little attention directed toward the amounts men are paid for donating or whether they should be paid at all. In contrast, as recently as 2019 a bill was introduced in the Arkansas state legislature seeking to outlaw egg donation unless the donor donates for free. John Moritz, State Measure Focuses on Eggs’ Donors; Bill Would Ban Efforts to Profit, Ark. Democratic Gazette (March 11, 2019), https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2019/mar/11/measure-focuses-on-eggs-donors-20190311-1/.

Sonia F. Epstein & Polina N. Whitehouse, Inheriting the Ivy League: The Market for Educated Egg and Sperm Donors, Crimson (Apr. 3, 2020), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2020/4/30/inheriting-the-ivy-league/; Paris Martineau, Inside the Quietly Lucrative Business of Donating Eggs, Wired (Apr. 23, 2019), https://www.wired.com/story/inside-lucrative-business-donating-human-eggs/; Egg Donor Wanted, B Students Need Not Apply, Stanford Daily (May 30, 2012), https://www.stanforddaily.com/2012/05/30/egg-donor-wanted-b-students-need-not-apply/.

Suzanne Holland, Contested Commodities at Both Ends of Life: Buying and Selling Gametes, Embryos, and Body Tissues, 11 Kennedy Inst. Ethics J., 263, 274 (2001) (arguing that “[f]or many of us, our sense of the dignity of humanity is fundamentally disturbed by the suggestion that that which bears the marks of personhood can be somehow equated with property. We do not wish to have certain aspects of that which we associate with personhood sold off on the market for whatever the market will bear.”).

Guide to Egg Donation for Asian Egg Donors, Conceivabilities (Oct. 15, 2019), https://www.conceiveabilities.com/about/blog/guide-to-egg-donation-for-asian-egg-donors (explaining that Asian egg donors are likely to make upward of $10,000 for a donation, whereas the base compensation rate is $8,000). However, some reports of higher compensation for certain ethnic groups provide only anecdotal evidence. For instance, one news article suggested that Asian women are being paid exorbitant amounts, yet the women cited in the article received rates below $10,000. See Shan Li, Asian Women Command Premium Prices for Egg Donation in U.S., L.A. Times (May 4, 2012), https://www.latimes.com/health/la-xpm-2012-may-04-la-fi-egg-donation-20120504-story.html#:~:text=The same market forces that,known as gametes or ova.

Side-effects of the medications required for egg donation include headaches, mood swings, nausea, and bloating due to the swelling of the ovaries that occurs when they are stimulated to produce extra eggs. Donor Egg Risks & Complications, Egg Donor Am., https://www.eggdonoramerica.com/become-egg-donor/donor-egg-risks-complications (last visited Aug. 2021). For a discussion of the relative dearth of knowledge regarding the long-term effects of egg donation, see Molly Woodriff, et al., Advocating for Longitudinal Follow-Up of the Health and Welfare of Egg Donors, 102 Fertility & Sterility 662 (2014). For an in-depth discussion of the potential ethical pitfalls of donation, see Holland, supra note 27, at 263. Ruth Macklin, What is Wrong with Commodification?, New Ways of Making Babies: The Case of Egg Donation (CB Cohen ed., 1996).

And there are certainly gendered dimensions to society’s discomfort or acceptance of reproductive commodification.

Steinbock, supra note 22 at 260.

Id. at 262.

Id. Notably, many actors in the fertility industry regularly claim they are not in the business of “buying eggs.” Egg donor program websites stress to potential donors that they are not purchasing the donors’ eggs but instead compensating them for the time and pain that is required due to the donation process. Tennessee Reproductive Medicine’s website, for instance, states that no compensation attaches to the eggs themselves. Become an Egg Donor in Chattanooga, Tenn. Reprod. Med., https://trmbaby.com/library/donation-surrogacy/egg-donation/egg-donor-4000-compensation/ (last visited Aug. 2021). But this widespread denial does not accord with reality. It is clear that American society, as a whole, has accepted the purchase of sperm. Sperm banks are not paying men to masturbate but are instead purchasing the output of that activity. Similarly, fertility agencies, egg agencies, and infertile couples are clearly purchasing eggs from women who are willing to sell while also compensating them for the time, effort, pain, and medical risks that are involved. And even donors themselves recognize that it is the eggs that are the focal point of the transaction. As one donor explained, “[d]onation is a term that is supposed to reflect that it’s a woman’s time, not the value of her eggs, that’s being paid for. But here was an industry offering me more per hour than I’d ever earned at a regular job. To say I’m selling feels more honest.” Ellie Houghtaling, I Sold My Eggs for an Ivy League Education—But Was It Worth It?, Guardian (Nov. 7, 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/nov/07/i-sold-my-eggs-for-an-ivy-league-education-but-was-it-worth-it.

Ethics Comm. of the Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Ethical Considerations of Assisted Reproductive Technologies, 62 Fertility & Sterility (Supplement 1) 47S (1994).

Ethics Comm. 2000, supra note 4, at 216.

Id. at 219.

Id. The ASRM guidelines (then and now) also stated that compensation should not vary according to the planned use of the oocytes, the number of quality of oocytes retrieved, the number or outcome of prior donation cycles, or the donor’s ethnic or other personal characteristics. Ethics Comm. of the Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Financial Compensation of Oocyte Donors: An Ethics Committee Opinion, 106 Fertility & Sterility e16 (2016). However, clinics routinely offer higher compensation rates for repeat donors and donors of certain ethnic or religious backgrounds (particularly Asian and Jewish), id.

Kimberly Krawiec, Sunny Samaritans and Egomaniacs: Price-Fixing in the Gamete Market, 72 Law & Contempo. Probs. 59, 75 (2009) (noting ASRM failed to explain where its numbers came from or why they might represent reasonable compensation for the additional burdens that the committee agreed egg donors faced); Levine, supra note 13, at 28 (noting that it was unclear whether compensation levels for sperm donors were appropriate in the first place and whether the sperm and oocyte donation process were sufficiently similar to justify the analogy).

Rene Almeling, The Business of Egg and Sperm Donation, 16 Contexts 68, 69 (2017); see also Egg Donation Clinic in Virginia, supra note 17 (explaining that egg retrieval requires sedation).

See Ethics Comm. 2000, supra note 4.

Robert W. Rebar, The Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Resolve, http://familybuilding.resolve.org/site/PageServer?pagename=pubs_asrm (last visited Aug. 2021).

Whether or not clinics and agencies were in fact complying with the guidelines prior to the lawsuit is not entirely clear. There is no evidence that ASRM removed any non-compliant clinics from its membership list, and anecdotal news reports often suggested that clinics and agencies regularly failed to comply with the guidelines. See Li, supra note 28; David Tuller, Payment Offers to Egg Donors Prompt Scrutiny, N.Y. Times (May 10, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/11/health/11eggs.html. But the reports of non-compliance are suspect, both because the actual women interviewed reported payments within the guidelines and because more comprehensive studies in 2005 and 2009 found that the majority of clinics and agencies were in fact staying within the $10,000 boundary. See Sharon N. Covington & William E. Gibbons, What is Happening to the Price of Eggs?, 87 Fertility and Sterility 1001, 1003 (2007); see also Johnson, supra note 24, at 365. What does seem clear is that some firms, particularly egg agencies, often did (and still do) place advertisements for donors that suggest egg donors can make extremely large sums. See Levine, supra note 13, at 31. But it is quite possible women who respond to these ads are not, in fact, paid as much as is advertised. Some fertility experts have suggested that agencies may use such ads as a “bait and switch;” once a potential donor reaches out, she may be told that the couple has already found a donor and given the opportunity to donate at a lower price to a different couple. Steinbock supra note 22, at 259. Furthermore, these ads often elide the fact that making more than $10,000 usually requires making multiple donations. For instance, one ad notes that a donor can “make up to $48,000 for donating her eggs,” but does not explain that to make that $48,000 she must agree to six separate donations for $8,000 each. FairFax Eggbank advertisement on file with author. Newspaper articles reporting high donor compensation rates also often gloss over the fact that the large payments reported required multiple donations. See Li, supra note 28 (reporting that one donor received $26,000 for three donations and leaving unspoken that this means the donor received an average of $8,600 per donation). Finally, common sense would tell us that the number of couples able to pay $50,000 or more for a single cycle of donor eggs, on top of the price of IVF, is not that large, id. And why would large numbers of couples pay such an exorbitant amount when hundreds of clinics across the U.S. offer eggs at a lower price?

Covington & Gibbons, supra note 42 at 1001.

Id. at 1001-02.

Id. (the Kamakahi plaintiffs attached this list to their complaint).

Id.

Id.

Indeed, Kimberly Krawiec wrote in 2009 (two years before the lawsuit was filed) that “the most intriguing question [the guidelines raise] is not whether [they] violate the Sherman Act—under existing precedent [they do]. Rather, the relevant question is how, given the government’s substantial enforcement resources and the presence of an active and entrepreneurial plaintiffs’ bar, this buyers’ cartel has managed to survive unchallenged since at least 2000.” Krawiec, supra note 38, at 60.

Lindsay Kamakahi donated her eggs at the Pacific Fertility Center, which at the time stated on its website that “[b]ecause of [its] continuing efforts to practice medicine within guidelines set forth by ASRM and SART, egg donors participating in our program will NOT be paid above $10,000 per cycle.” Complaint, supra note 2, at 12.

Under the Sherman Act of 1890, “[e]very contract. . .or conspiracy. . .in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States. . .is declared to be illegal.” 15 U.S.C. § 1.

See Complaint, supra note 2, at 16.

Lindsay Kamakahi v. Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s First Amended Class Action Complaint at 10, no. 3:11-CV-1781 U.S. Dist. Ct. (N.D. Cal. July 15, 2011) [hereinafter Motion to Dismiss].

In a very small number of cases, courts have considered social welfare or other noneconomic justifications for anticompetitive behavior. A key example is United States v. Brown University, in which the third circuit held that an agreement among eight Ivy League schools to collectively determine the amount of financial assistance awarded to commonly admitted students must be evaluated under a full rule of reason analysis. United States v. Brown Univ., 5 F.3d 658, 678 (3d Cir. 1993). But even in Brown the Court noted that social policy alone was an insufficient justification for anticompetitive behavior. Thus, social welfare arguments, standing alone, would not be sufficient to save ASRM’s guidelines. See Brown, 5 F.3d at 669 (concluding that restraint on competition cannot be justified solely on the basis of social welfare concerns).

Covington & Gibbons, supra note 42, at 1001.

Motion to Dismiss, supra note 52, at 16-17. ASRM argued that the guidelines were not motivated by profit-maximization concerns but ethical concerns and thus fell outside of the per se rule, id.

Id. at 6-10.

Texaco Inc. v. Dagher, 547 U.S.1, 5 (2006).

Motion to Dismiss, supra note 52, at 7 (citing Broad. Music, Inc. v. Columbia Broad. Sys., 441 U.S. 1, 9 (1979)).

Id. (citing Arizona v. Maricopa Cnty. Med. Soc’y, 457 U.S. 332, 344 (1982)).

For instance, “unlike in those rare cases in which courts have allowed naked collusion on price or output, collusion on egg prices does not enable an otherwise nonexistent market to operate or enhance the quality or diversity of consumer choice.” Krawiec, supra note 38, at 83; see, e.g., NCAA v. Bd. of Regents of Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 117-19 (1984) (holding that the special nature of athletic competition requires some cooperation); Broad. Music, Inc. v. CBS, 441 U.S. 1, 23 (1979) (finding that the collusion at issue enabled the creation of a product package that no individual could offer, thus enhancing consumer choice and increasing the volume of music sales); United States v. Brown Univ., 5 F.3d 658, 682-84 (3d Cir. 1993) (finding that collusion improved the product itself because socioeconomic diversity enhances the educational experience.). Instead, capping the amount of compensation a donor can receive is more likely to prevent higher income donors from donating in the first place, thereby decreasing supply. See Krawiec, supra note 38, at 83.

Goldfarb v. Va. State Bar, 421 U.S. 773, 787-88 n.17 (1975).

Goldfarb, 421 U.S. at 791-92; Maricopa, 457 U.S. at 351-52.

Individual class members were free to file individual actions pursuing damages for past donations, but would release ASRM from all claims for injunctive, declaratory, or other equitable relief related to egg donor compensation. Final Order, supra note 6.

Id. at 2.

Final Order, supra note 6, at 3.

See Complaint, supra note 2, at 16.

Thomas Grubisich, Va. Lawyers Cut Title Search Charges: Fees Cut for Title Searches, Wash. Post, May 31, 1975, at B1.

In fact, this paper was inspired from my own personal observation that the compensation rate for donors at the Duke and UNC Fertility centers had not changed during my years as a PhD student and then JD student.

See Goldfarb v. Va. State Bar, 421 U.S. 773, 777-79 (1975).

See Complaint, supra note 2, at 1.

Kimberly Krawiec, Lessons from Law About Incomplete Commodification in the Egg Market, 33 J. Applied Philosophy 160, 160 (2016).

Kimberly D. Krawiec, Markets, Morals, and Limits in the Exchange of Human Eggs, 13 Geo. J. L. & Pol’y 349, 365 (2015). More recently, some clinics have started to suggest that egg donation is synonymous with “rescuing” eggs. California IVF, for instance, tells donors that “[f]ertility medications rescue eggs that would have otherwise died.” “What better way to make use of those extra eggs,” they ask, “than to donate [those eggs] to a woman struggling to become a mother.” Becoming an egg donor, Cal. IVF Fertility Ctr., https://www.californiaivf.com/egg-donor/ (last visited Jan. 30, 2022).

For instance, Circle Surrogacy has a page for potential donors titled “The Benefits of Egg Donation.” Although the page states that there “is no right or wrong reason for applying” to be an egg donor, the fact that the clinic ranks compensation as number 5 in its list of the five benefits of egg donation is telling. Compensation is outranked by “Gain[ing] and [sic] incredible sense of fulfillment,” “Match[ing] with intended parents who meet your criteria,” “Ability to choose Known and Anonymous egg donation,” and “Full support from an experienced egg donation team.” The Benefits of Egg Donation, Circle Surrogacy, https://www.circlesurrogacy.com/egg-donation/benefits-of-egg-donation (last visited Jan. 30, 2022).

I Donated My Eggs and I Won’t Do It Again, We are Egg Donors, https://www.weareeggdonors.com/blog/2015/11/13/i-donated-my-eggs-and-i-wont-do-it-again (last visited Aug. 2021) [hereinafter We Are Egg Donors].

Baby Steps Surrogacy, for instances, states that it will not work with potential donors who are only motivated to donate in the hopes of being compensated. According to their website, women who are “only in it for the money” are “not usually able to commit to the entire egg donation process” and this is why the agency is “only interested in working with women who are donating eggs out of good intentions.” Requirements to Donate Eggs, Baby Steps Surrogacy, https://babystepssurrogacy.com/sperm-and-egg-donors/requirements-donate-eggs/ (last visited Sept. 17, 2022).

We Are Egg Donors, supra note 73.

Donor Information, Asian Egg Donation, https://www.asianeggdonation.com/egg_donor.html#4 (last visited Sept. 17, 2022); Become an Egg Donor: Program Information, Eggceptional Match, https://www.donatedeggs.com/become-an-egg-donor/ (last visited Sept. 17, 2022).

About 17% of the firms in my dataset do not provide transparent pricing data. See infra discussion Part III.

See, e.g., How to Become an Egg Donor, Brown Fertility, https://www.brownfertility.com/egg-donation/become-an-egg-donor (last visited Sept. 17, 2022).

Many, but not all. Some firms were quite willing to share their compensation rates when I called to inquire.