INTRODUCTION

This Article began as a search for answers. Why did a close family member pass away unexpectedly after being discharged from an observation unit (“OU”) two days prior? Why was this chronically ill patient, with multiple comorbidities and unable to ambulate, in an OU in the first place? The answers we found illustrate a health care system troubled with conflicts of interest, providers who feel powerless against their administrators, and healthcare institutions that feel powerless against Medicare. In the end, we discovered that patients have the least amount of power in our current healthcare system, leaving them at risk of receiving substandard care, and for many seniors, facing medical bankruptcy. It’s enough to give people nightmares and to make one seriously fear growing old in the United States.

Americans have been told that they just need to work until Medicare and Social Security kick in–age 65 for Medicare and somewhere between ages 66 and 67 for Social Security, depending on your birth year.[1] Once reaching these “magical ages,” American citizens should be able to receive a monthly check from Social Security to cover their living expenses[2] and Medicare will begin to cover many of their medical costs.[3] However, the current reality paints a very different picture.

Medical debt is a growing crisis in the United States leaving many Americans with no other option but to file bankruptcy.[4] While there is no single definition of “medical bankruptcy,” a 2009 study classified a “medical bankruptcy” as a bankruptcy filing where a person had to either: (1) mortgage their home to pay medical bills; (2) had medical bills greater than $1,000; or (3) had lost at least two weeks of work due to illness.[5] According to this definition, 62.1 percent of all bankruptcies in the United States can be classified as “medical bankruptcies.”[6]

Even more troubling is that the rate of citizens over the age of 65 who filed for bankruptcy increased approximately 204% from 1991 to 2016.[7] Social scientists analyzing data pulled from the Consumer Bankruptcy Project tied this increased trend of bankrupt seniors to the extremely high cost of health care.[8] But health care in the United States has always been expensive relative to other first world countries, so why are so many seniors finding it harder to cover their health care costs now more than ever?

This Article postulates that the force driving the unaffordable health care costs for the Medicare population is the push by Medicare to provide more hospital care in an outpatient setting. By classifying a patient’s care as outpatient, Medicare shifts some of the financial burden of the hospital medical bills onto the patient,[9] and in the case of skilled nursing care needed after outpatient hospital care, Medicare shifts the entire financial burden onto the patient.[10]

A prime example of this shift in financial burden and the negative ramifications for the patients can be seen by analyzing the increased use of outpatient OUs in the Medicare population. A 2019 study conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health found that nearly 47.3 percent of patients experience a status change– a shift from inpatient status to outpatient status or vice versa– during their hospital stay.[11] A November 2021 article in Health Affairs found that the most significant shift to outpatient OU use was seen in Medicare patients with the highest numbers of chronic conditions.[12]

Numerous articles have been written cautioning against the use of OUs for patients with multiple comorbidities because of their need for numerous medications.[13] Dr. David Meltzer from the University of Chicago has done extensive research on the subject, finding that patients with multiple comorbidities have better outcomes at a lower cost when treated by a care team familiar with their health history.[14] So why, in the presence of data indicating the need for inpatient placement, do the majority of patient status shifts occur in Medicare patients with multiple chronic conditions? The answer lies in the financial conflict of interest created by the 2006 implementation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Recovery Audit Program (RAC),[15] the implementation of the Medicare Two-Midnight rule in 2013,[16] and the pressure these rules place on hospital utilization review committees to assign patients to outpatient status.[17] These external cost control measures have resulted in a loss of physician autonomy in determining the best placement for their patients.[18]

This Article aims to address this loss in physician autonomy in two ways: (1) educate clinicians regarding the ethical considerations that should be utilized when determining patient placement; and (2) arm clinicians with the power to disrupt the detrimental conflicts of interests inherent in the healthcare system so that they feel confident advocating for the best interests of their patients. In order to achieve these goals, the Article has been broken down into parts. The first part provides an understanding of what OUs are, the various types of OUs employed in the U.S. healthcare system, and the pros and cons to each. The second part examines the reasons for the increased use of OUs, the financial conflict of interest Medicare’s reimbursement rules creates for hospitals, and the two types of harm Medicare patients suffer as a result of being placed in an OU rather than admitted as an inpatient. The third part chronicles the distressing patient stories highlighted in Alexander v. Azar[19] case, as well as patient testimonials reported in the news, to illustrate how the improper use of OUs negatively impacts patient care and potentially increases patients’ financial burden. The fourth part discusses the four principles of bioethics as described by Tom L. Beauchamp and James F. Childress and how they can be applied to OU placement decisions. The final part utilizes a patient case study to illustrate how the Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade Four-Box Approach to clinical medical ethics can assist providers and hospitals in determining patient placement within the hospital when discharge from the Emergency Department (ED) is not recommended.

I. OUs: What they Are, the Various Types, and the Pros and Cons of Each

The first step to ensuring the ethical use of OUs is to understand that (1) there are several types of OUs; (2) each type has pros and cons to its use; and (3) appropriate use of each type of OU is defined by different inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the US hospital system, OUs are referred to by many different names. Common names associated with OUs include Clinical Decision Unit (CDU), Chest Pain Unit, ED Short Stay Unit, and ED Observation Unit.[20] OUs came into existence several decades ago to address a growing need to take care of ED patients.[21] Beginning in the late 1990s, the number of annual ED visits increased more than double the rate of population growth.[22] At this same time, the number of EDs in the US declined, and the complexity of the ED evaluation process increased, due to advanced imaging technology.[23] On top of this already apparent bottleneck in the healthcare system, lack of inpatient beds resulted in many patients being boarded in the ED.[24] OUs were created to help solve these problems by allowing ED physicians to transfer patients to a designated unit within the hospital where they could continue to be monitored while test results were pending.[25] This gave ED physicians a third option to the traditional method of either (1) admitting the patient to inpatient services, or (2) discharging the patient home.

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), OUs were created to address:

[A] well-defined set of specific, clinically appropriate services, which include ongoing short-term treatment, assessment, and reassessment before a decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. Observation services are commonly ordered for patients who present to the emergency department and who then require a significant period of treatment or monitoring in order to make a decision concerning their admission or discharge.[26]

OUs come in all different shapes and sizes. Michael Ross and his colleagues broke them down into four types.[27] Type I OUs are protocol-driven, discrete units usually located adjacent to or within an Emergency Department (ED) and staffed by emergency physicians and/or advanced practice providers (APPs).[28] Type II OUs offer discretionary care and are also referred to as “open units.”[29] In Type II units, while the unit is typically based in the ED, physicians from various specialties care for the patient.[30] Type III units are protocol-driven units that can be housed anywhere in the hospital.[31] They are often referred to as “virtual observation units” in which different physicians, including emergency physicians and hospitalists who are knowledgeable about observation protocols, manage patient care.[32] Type IV units are the most widely used with approximately two-thirds of US hospitals delivering observation care without using a dedicated OU.[33] In Type IV units, care is provided in a bed anywhere in the hospital (usually an inpatient bed) with multiple providers caring for the patients with varying management styles.[34] Because Type IV units are the most widely used and Type I units are considered the gold standard for observation care, the following discussion will focus on these types of OU uses.

A. Designated Type I OUs are Considered the Best Practice

According to Ross, Salvador-Kelly, and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), a designated OU manned by emergency physicians is the best practice.[35] Ross and his colleagues found that Type I OU’s were associated with the best outcomes, including, “lower costs, shorter lengths-of-stay, lower rates of inpatient admissions, less diagnostic uncertainty, greater patient satisfaction, better clinical outcomes, and improvements in the use of hospital resources.”[36] Salvador-Kelly found that the “data supports Type I OUs as better for patient outcomes and [length of stays].”[37] ACEP contends Type I OU’s: (1) promote efficiency within the healthcare system; (2) reduce costs for the patient and maximize reimbursement from Medicare; and (3) reduce medical errors by promoting continuity of care.[38]

Type I OUs promote efficiency by allowing emergency physicians to transfer patients who are stable but who do not yet have a clear diagnosis or plan of care out of the ED so more critical patients can be seen in ED beds.[39] This results in fewer diversions from the ED because of long wait times or capacity limits.[40] In the OU, patients continue to be monitored as diagnostic tests come back and a clear understanding of the patient’s diagnosis can be determined.[41] This ability to free up ED beds, while at the same time offering necessary care to OU patients, is critical to high census hospitals where the only options for patient care would be housing the patient in an ED bed, discharge, or admission to the hospital.[42]

In addition, Type I OUs allow hospitals the best opportunity to decrease out-of-pocket costs to the patient and maximize hospital reimbursement from Medicare.[43] When utilized correctly, the average patient observation copay is about half as much as the inpatient copay.[44] These cost savings can result in greater patient satisfaction as measured by Press Ganey scores.[45] Medicare encourages hospitals to keep patients on observation status because OUs are considered an outpatient service covered under Medicare Part B, which is less expensive than inpatient status which is covered under Medicare Part A.[46]

Properly utilized Type I OUs also decrease the chance of medical error from either premature discharge or errors related to transfers to other hospital services.[47] Adding an additional transfer to another location when not absolutely necessary increases the risks associated with communication errors during nursing and physician staff hand-off, physician and medication orders, and patient transport.[48]

In Type I OUs, the decision to order observation services, as opposed to formal inpatient admission, is made based on the capabilities of the OU, the clinical judgment of the treating physician, and the application of observation protocols.[49] Unfortunately, for patients who receive observation care in a Type IV OU, which is not adjacent to the ED or staffed by an emergency medicine practitioner, the decision whether to formally admit a patient as an inpatient or order observation services is made by applying the Medicare Two-Midnight Rule.[50]

B. Creep in Type IV OUs Reduce the Efficiency and Effectiveness of the OU Care

The disparity in the decision making criteria for patient placement in Type IV OUs might not be so problematic if the use of Type IV OUs were limited to patients with a finite set of diagnoses as was intended under the Type I OU structure.[51] However, Type IV OUs which are not housed within the EDs have expanded the diagnoses criterion to include a variety of presenting symptoms.[52] This creep in OU use both negates the specialized nature of the Type I OUs, and poses severe problems for the patient financially and in terms of the patient’s overall health.[53]

Ross, Salvador-Kelly, and Napolitano all agree that the best practice for OU use is to limit admissions to single discrete medical conditions where there is a well-defined problem and plan for care.[54] Ross argues that OU use should be excluded as an option where there is no clear diagnosis or plan for care documented or where the patient clearly should be admitted but the service does not want to admit.[55] Salvadore-Kelly advises that “[c]onditions in older adults to consider for exclusion to the OU include, likely need for placement in a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility, failure to thrive, exacerbation of chronic problems, inability to ambulate, altered mental status, and a projected length of stay (LOS) of greater than 24 hours.”[56] Salvadore-Kelly notes that placing geriatric patients in the OU may cause financial hardship.[57] A more detailed discussion of the drivers of this OU creep will be discussed in Part II and a detailed discussion of the harms faced by patients incorrectly diverted to OU care will be addressed in Part III.

II. Reasons for the Increased Use of OUs

A common axiom in health care is that the patient’s treating physician is in the best position to know what medical care best serves the patient’s interest. This is underscored by CMS’s own rule related to admission of patients and coverage under Medicare Part A, which states:

(a) For purposes of payment under Medicare Part A, an individual is considered an inpatient of a hospital, including a critical access hospital, if formally admitted as an inpatient pursuant to an order for inpatient admission by a physician or other qualified practitioner in accordance with this section and §§ 482.24(c), 482.12(c), and 485.638(a)(4)(iii) of this chapter for a critical access hospital. In addition, inpatient rehabilitation facilities also must adhere to the admission requirements specified in § 412.622.[58]

(b) The order must be furnished by a qualified and licensed practitioner who has admitting privileges at the hospital as permitted by State law, and who is knowledgeable about the patient’s hospital course, medical plan of care, and current condition. The practitioner may not delegate the decision (order) to another individual who is not authorized by the State to admit patients, or has not been granted admitting privileges applicable to that patient by the hospital’s medical staff.[59]

Despite being granted such authority to issue an inpatient order, the question this Part attempts to answer is why physicians feel like they have no say in whether the patient is admitted as an inpatient or placed in an OU as an outpatient. The answer is not simple. It involves complicated CMS rules, Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs)[60] who make decisions based on computer algorithms, hospital administrators who struggle to receive payments for services rendered to Medicare patients, and the shift to hospital employment of physicians. All of these issues converge to create a financial conflict of interest for both the hospital and the physician that ultimately overrides the best interests of the patient.

The second step to ensuring the ethical use of OUs is to understand the origin of this financial conflict of interest. This Part will identify and explain the complicated Medicare rules at play in patient placement decisions and Medicare reimbursement; analyze a recent District Court of Connecticut case, Alexander v. Azar; and explore how the testimony offered in this case illustrates how these Medicare rules, the use of MACs, and the pressures CMS places on hospitals ultimately erode the physician’s sense of autonomy in making care decisions on behalf of his or her patients.

A. Medicare Rules and their Impact on Hospital Reimbursement and the Patient’s Financial Burden

Medicare provides public health insurance coverage for persons 65 or older, individuals with kidney disease, and those on permanent disability.[61] Medicare Part A is free to most Medicare beneficiaries, which includes coverage for hospital services and skilled nursing care.[62] However, formal admission to a hospital is a precondition to payment for such services.[63] When a patient is placed on “observation status” and therefore not treated as an inpatient, the patient becomes responsible for paying for the hospital services and any post-hospital skilled nursing care out of pocket, unless he or she has other insurance coverage, such as Medicare Part B or private insurance.[64] Medicare Part B covers outpatient hospital services, but not skilled nursing care.[65]

1. The creation of the recovery audit contractors and their impact on patient placement determinations

In 2003, Congress enacted the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act,[66] which authorized the use of recovery audit contractors (RACs) to identify and recover overpayments in Parts A and B of the Medicare program.[67] The audits specifically targeted hospitals for short inpatient hospital stays, which have substantially increased Medicare costs.[68] In addition, Condition Code 44,[69] authorized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2004, allowed providers to retroactively change a patient’s status from inpatient to outpatient if the following criteria were met: (1) the status change took place prior to discharge or release while the beneficiary was still a patient of the provider; (2) the provider had not submitted an inpatient admission claim to Medicare; (3) a physician agreed with the utilization review committee’s decision (to be discussed later in Part II); and (4) the physician’s agreement with the committee’s decision was documented in the patient’s medical record.[70]

The RACs based their determinations on whether inpatient hospital admission was appropriate based on guidance found in The Medicare Benefit Policy Manual.[71] The Policy Manual established a 24-hour benchmark for inpatient admissions whereby physicians should order admission for patients who are expected to need hospital care for 24 hours or more, and treat other patients on an outpatient basis.[72] Medicare recognized that this was often a complex decision, requiring the physician’s judgment as a medical professional based on a number of factors.[73] These factors included the medical history of the patient and the patient’s current medical needs.[74] But this decision was also influenced by the types of medical facilities available for inpatients and outpatients at the location where the patient was being treated, the appropriateness of treatment for the patient in each of those settings, and, of course, the admission policies of that specific hospital.[75] As a foreseeable result, between 2007 and 2009 there was an eighty-eight percent increase in the number of Medicare patients that spent three or more days in the hospital under observation (an outpatient status), a shift away from inpatient admissions.[76]

2. The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) and its impact on patient placement decisions

Medicare strives to provide access to health care that is both cost-effective and high quality.[77] One of Medicare’s top priorities in reducing costs and improving care is preventing potentially avoidable hospital readmissions.[78] Approximately 1.8 million Medicare patients are readmitted each year, costing an estimated $26 billion.[79] Of that, roughly $17 billion comes from readmissions that were potentially avoidable.[80] To combat these readmissions and their costly price tags, Medicare enacted the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) in 2012.[81] This program created financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected 30-day readmission rates for specific conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, pneumonia, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and elective primary total hip arthroplasty and/or total knee arthroplasty in Medicare patients.[82] As of 2013, hospitals can lose up to three percent of their Medicare reimbursements under this program when readmission rates exceed expectations.[83] Medicare calculates readmission rates by determining the prevalence of readmission for specified clinical conditions over a three-year period.[84] However, time spent in observation units may be skewing the success of HRRP.[85]

HRRP defines only inpatient hospitalizations, not observation stays or ED visits, as readmissions.[86] As a result, the success of HRRP has been artificially inflated.[87] While readmission rates have decreased for targeted conditions, rates of observation stay and ED visits after inpatient stays for those conditions have increased.[88] As a result, there has been no change in the rate of patients who return to a hospital within 30 days after discharge.[89] In fact, HRRP creates strong incentives for hospitals to treat patients in EDs or OUs in order to avoid readmissions, even if inpatient hospitalization would provide better care for the patient.[90]

Another major flaw to the HRRP is that penalties for high readmission rates are much higher than penalties for high mortality under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program.[91] As a result, several studies suggest that the increase in observation unit use is due to a shift in triage patterns rather than to improvements in quality of care.[92] Specifically, these findings have shown an increase in post-discharge mortality for Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure and pneumonia, which was concentrated among those who were not readmitted after discharge, but instead remained in the ED or were sent to an OU.[93] These findings also demonstrate the alarming extent of harm that can be suffered by a patient when a provider’s decision to place the patient was based primarily on financial interests instead of genuine need.

3. The Two-Midnight Rule: the final nail in the coffin of physician autonomy over patient placement decisions

In 2013, CMS refined its earlier guidance related to hospital admission for Medicare patients, creating what is now known as the “Two-Midnight Rule.”[94] Under this rule, if “the physician expects to keep the patient in the hospital for only a limited period of time that does not cross 2 midnights, the services are generally inappropriate for inpatient admission and inpatient payment under Medicare Part A.”[95] The physician’s expectations, again, are to be based on complex medical factors, which might include the patient’s medical history and any comorbidities, the severity of the presenting symptoms, the patient’s current medical needs, and the risk that the patient might experience an adverse event.[96] Ultimately, this is meant to be a decision entirely within the physician’s discretion and professional judgment.[97] CMS modified the Two-Midnight Rule in 2015 to add clarity on this point, creating a new case-by-case exception to the two midnight requirement.[98] The updated language reflected a physician’s ability to override the Two-Midnight Rule when “based on the clinical judgment of the admitting physician and the medical record support for that determination” of hospital admission was necessary, regardless of the expected length of the patient’s stay or the patient’s receipt of an inpatient-only procedure.[99]

However, the Two-Midnight Rule has created financial and physical burdens to patients that ought not be overlooked. Medicare assesses penalties to hospitals for inpatient stays of less than two midnights.[100] Such management incentivizes treating patients in an outpatient manner unless there is no doubt they would be hospitalized for more than two days.[101] A patient is presumed to be an inpatient if he or she stays for at least two midnights consecutively; such a patient will be covered under Medicare Part A and be required to pay a one-time deductible of $1,556 (in 2022) for the total medical bill.[102] On the other hand, if a patient is presumed to require a stay for less than two midnights, he or she would be placed under observation services which is covered under Medicare Part B, and would be responsible for 20 percent copayments for each service provided during his or her stay.[103] While the copayment for a single outpatient hospital service can’t be more than the inpatient hospital deductible, a patient’s total copayment for all outpatient services may be more than the inpatient hospital deductible.[104]

This admission decision has financial impacts that extend beyond coverage for just the hospital services under Medicare.[105] After a hospital stay, it is possible that a patient may need extended care services at a skilled nursing facility (SNF).[106] However, eligibility for SNF care under Medicare Part A requires an inpatient hospital admission of at least three consecutive calendar days, not including the date of discharge.[107] The District Court in Azar noted that according to CMS’s interpretation of this requirement, SNF coverage for patients who are not formally admitted to the hospital as inpatients for at least three days, even though the patients’ total stay at the hospital, including time spent as an outpatient receiving observation services, was three days or more, would not qualify for SNF care covered by Medicare Part A.[108] In other words, inpatient status commences on the day of admission, but the time spent in an observation unit or in the emergency room prior to (or in lieu of) an inpatient admission to the hospital does not count toward the 3-day qualifying inpatient hospital stay necessary for Medicare to cover care at an SNF.[109] Under Medicare rules, a person who appears at a hospital’s emergency room seeking examination or treatment and is placed on observation has not been admitted to the hospital as an inpatient; instead, the person is considered to be receiving outpatient services which are billed under Medicare Part B or private insurance.[110]

As a result, many patients who are placed in observation but require or would benefit from SNF care do not end up receiving such benefit because they do not qualify under Medicare Part A and it is not covered under Medicare Part B. They are therefore unable to afford the SNF out-of-pocket expense. It is important to recognize that many of these patients would have qualified for SNF but for the hospitals’ incentives to place them in an OU due to the reimbursement parameters that the Medicare rules dictate. Without coverage, the out-of-pocket cost for the patient can be significant, and at times result in medical bankruptcy or serious financial harm to the patient, as will be discussed in Part III of this Article. Without SNF coverage, a patient’s health and/or recovery may be significantly delayed and/or harmed.

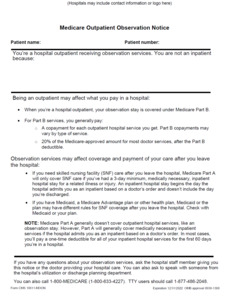

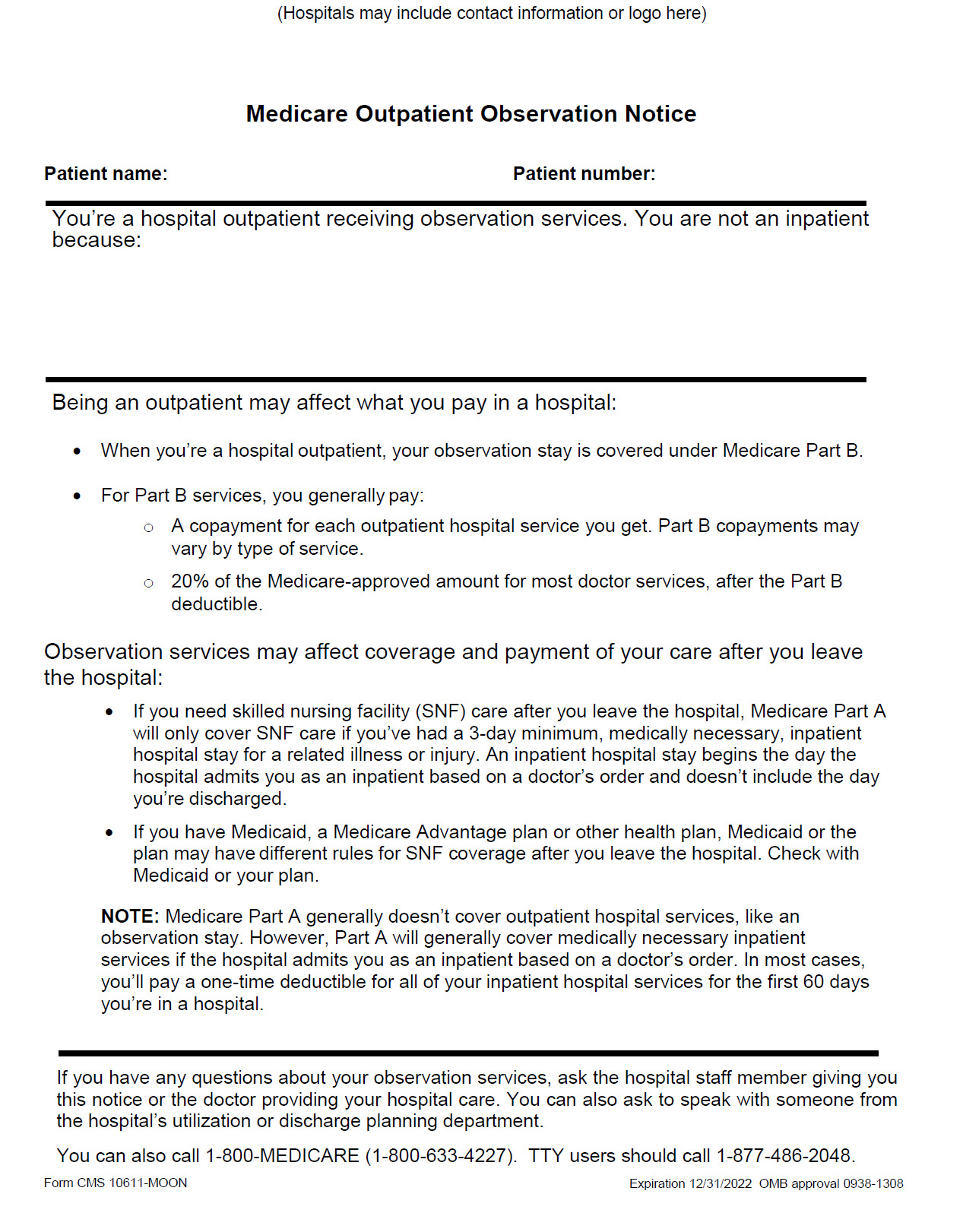

From a practical point of view, if a Medicare beneficiary is placed in an OU for more than 24 hours, hospitals are required to provide them with the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice (“MOON”).[111] The purpose of this notice is to explain to the beneficiary that they are receiving services as an outpatient and the financial implications of such treatment.[112] The MOON template issued by CMS explains that treatment in an OU is not covered under Medicare Part A and that placement on observation status may impact the patient’s eligibility for SNF care.[113] However, the MOON template does not offer any guidance to patients on how they might challenge their admission decision with the hospital.[114]

B. The Alexander v. Azar Case Highlights the Negative Effect the CMS Rules Have on Physician Autonomy to Determine Patient Hospital Status

A recent March 2020 ruling from the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut highlighted the pervasive financial conflicts of interests the Medicare rules place upon hospitals.[115] The question at issue in Alexander v. Azar was whether the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution requires the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human services to afford Medicare patients the opportunity to challenge decisions made by hospitals that negatively affect a patient’s Medicare coverage. [116] The District Court noted that under the current framework, “the patient has no right to a say in the doctor’s decision about whether to admit him or her as an inpatient, and no means to challenge it.”[117] This holds true even in cases where the hospital’s utilization review team, a team each hospital must have in place to review doctor’s decisions under the applicable mandatory national standards for treatment under Medicare, disagrees with the doctor’s admission decision and asks them to change it.[118]

Perhaps the most shocking revelation from the Azar case was the testimony of the physicians who, according to Medicare’s own rules, are charged with determining whether a patient should be admitted as an inpatient or placed in an OU as an outpatient. According to the testimony of numerous physicians from various types of OUs, it was found that only physicians who work in emergency department observation units (EDOUs) are free to make the decision to order observation services as opposed to formal inpatient admission without applying the Two-Midnight Rule or any other government-specified criteria.[119] For patients who receive observation services outside of an EDOU, the testimony of the physicians indicated that the decision to admit a patient as an inpatient as opposed to ordering observation services was done by applying the Two-Midnight Rule.[120] The most shocking testimony occurred when several of the treating physicians testified that they believed that the utilization review team made the final call as to the patient’s status.[121] The following are excerpts of the testimony:

[O]ftentimes the utilization review team makes the final call.[122]

[W]e’re pretty much coached that you follow what [utilization review] tell[s] you.[123]

In addition, the Court noted that there was evidence “that hospitals and physicians tell patients that the decision to place them on observation rather than admit them as inpatients is made by utilization review personnel and not the treating physician.”[124]

Ultimately, the Court determined that the utilization review team’s decisive influence to change a patient’s status from inpatient to outpatient stems from three factors: (1) treating physicians often perceive utilization review personnel to be the experts regarding eligibility for Part A coverage for inpatient hospital services; (2) treating physicians outside of dedicated EDOUs generally view the distinction between formal inpatient admission and designation as an outpatient receiving observation services as a billing distinction divorced from decisions regarding appropriate medical care; and (3) hospitals have more at stake with respect to the inpatient-observation distinction than treating physicians.[125]

As the Azar case highlights, not only do patients lose autonomy over their own care, but physicians feel as though they have lost the autonomy to have a say in their patient’s treatment plan once the utilization review committee issues a determination.[126] This is especially problematic when a patient is reclassified as an outpatient receiving observational services when they had initially been told they were being admitted to the hospital.[127] Such a scenario can lead to drastic financial consequences for the patient due to the differences in coverage under Medicare.[128]

C. An Overview of the Conflicting Interests Created by Medicare Rules

In summary, the use of RACs, the implementation of the HRRP, and finally the creation of the Two-Midnight Rule create financial conflicts amongst Medicare, physicians, and patients, whereby hospitals exert pressure on physicians to increase the use of OUs to avoid short inpatient stays, the HRRP readmission penalty, and unnecessary payment denials by RACs.[129] A recent 2021 study confirmed the association with increased use of OUs and the implementation of the Medicare Two-Midnight Rule,[130] and a 2019 study confirmed that approximately 47% of patient placement decisions are changed while the patient is still in the hospital.[131] Of those status changes, the greatest shift from inpatient status to OU use was seen in Medicare patients with five or more chronic conditions.[132] These findings are troubling for many reasons, least of which is that the only person with no say in the decision to be admitted to the hospital or placed in an OU is the patient.[133] The following Part will explore how the inappropriate use of OUs place an unfair financial burden on Medicare patients, as well as illustrate the negative impact these decisions are having on patients’ health.

III. Medicare’s Goal of Controlling Healthcare Costs Creates a Financial Conflict of Interest for Healthcare Institutions which Results in Increased Litigation and Poorer Patient Outcomes

In clinical medical ethics, the cost of healthcare should rarely, if ever, factor into the consideration of what care a provider recommends for a patient.[134] This means that a provider should not limit care to a patient because of fears the patient is uninsured and the provider will not be paid.[135] Unfortunately, one consequence of Medicare’s two waves of reforms is to make providers cost conscious when providing care.[136] This is acceptable if the quality of care is not diminished and the patient is in agreement with the plan of care, but ethically and legally impermissible when money-saving measures result in patients receiving substandard care or deceptively shifting the financial burden of the care onto the patient.[137]

The third step to ensuring the ethical use of OUs is to understand the negative consequences for patients inappropriately placed in an OU. This Part highlights real-life patient stories and data analytics research of patient outcomes to illustrate the physical, emotional, and financial harms patients suffer as a result of being placed in an OU rather than admitted to the hospital even though for these patients, the total time they spent in the hospital would have qualified them for Medicare Part A coverage and subsequently post-discharge SNF care.

A. The Patient Stories Highlighted in Alexander v. Azar Illustrate a Healthcare System that Fails to Protect the Patient’s Autonomy or Ensure the Best Interests of the Patient

Alexander v. Azar provides ample evidence of the physical, emotional, and financial harm patients and their families encounter with improper OU assignment.[138] In his opinion, Judge Michael P. Shea masterfully sets the scene with his opening paragraph:

An elderly person’s arrival at a hospital is a stressful moment. The person might arrive in an ambulance. He or she might be in pain, suffering shortness of breath, or showing other troubling symptoms. Worried family members might wonder if their sick parent or grandparent will ever see the outside world again once he or she passes through the hospital’s doors. One question that might not be uppermost in their minds at the moment—but that may soon emerge to add to the stress of the experience—is who will pay for the elderly person’s medical care.[139]

As Judge Shea notes, “[u]nder the current Medicare regulations, the patient has no right to a say in the doctor’s decision about whether to admit him or her as an inpatient, and no means to challenge it.”[140] Even more troubling to Judge Shea and the plaintiffs is that the physician’s decision whether to admit the patient as an inpatient is not the final word on the matter. The decision is subject to review by the hospital’s “utilization review staff,”[141] which on occasion disagrees with the physician’s decision and asks him or her to change it, which more often than not, he or she will do.[142] This is particularly troubling to the patient when the physician’s order admitting the patient is changed to one placing the patient on “observation” status.[143] The following are patient stories that were highlighted in the Alexander opinion.

Ervin Kanefsky stayed at a hospital for five days after sustaining an evulsion fracture of the shoulder.[144] Shortly before being discharged, Mr. Kanefsky was informed that the hospital administration changed him from inpatient status to observation status and as a result, Medicare was not going to pay for his inpatient rehabilitation services.[145] According to Mr. Kanefsky, his treating physician, was “aghast” and exclaimed, “What?. . . I put this man as an inpatient.”[146] When Mr. Kanefsky asked whether his treating physician could do anything about the status change, his physician responded that he could not.[147] In a letter he later received from the hospital, he was informed that his case was reviewed by the Utilization Review team and the reviewer determined that he still qualified for observation status.[148] As a result of his status being changed to observation, Mr. Kanefsky did not qualify for SNF coverage and had to pay close to $10,000 for his SNF stay.[149]

Andrew Roney was hospitalized for three nights.[150] Like Mr. Kanefsky, he was initially admitted as an inpatient, but his status was changed to observation prior to his discharge.[151] He received a notice stating, “Your stay is being classified for billing purposes as ‘Observation’ stay, rather than as inpatient admission. . . . Assigning a classification for billing purposes is required by your insurance. Please note, however, that the quality of care is exactly the same regardless of whether your stay is billed observation or inpatient.”[152]

Martha Leyanna was hospitalized for seven nights and, similar to Mr. Kanefsky and Mr. Roney, her status as an inpatient was changed to observation prior to her discharge.[153] Ms. Leyanna’s daughter and granddaughter attempted to challenge her placement on observation, the hospital informed them that the decision to change her status was made by the utilization review committee.[154] The granddaughter of Ms. Leyanna testified at trial that her grandmother had to move from an SNF to a facility providing a lower level of care because she could no longer afford to pay for the SNF care.[155] This facility was unable to provide rehabilitative care she needed and she never regained independent mobility.[156] Ms. Leyanna’s SNF bill totaled $10,600 which she had to pay out-of-pocket.[157]

B. The Stories of the Patients Featured in the Azar Case are Not Unique

Other patients who either have not had the opportunity to seek remedy through or choose not to engage in legal proceedings have also shared their stories in the news.[158] These news stories further illustrate the significant hardships faced by patients as a result of the unethical use of observation services.

Catherine Fitzgerald was sent to the ED after a serious fall.[159] The ED doctor informed Ms. Fitzgerald’s daughter that she had to be admitted to the hospital’s OU to figure out her diagnosis.[160] Her daughter was alarmed by the words “OU,” but the doctor assured her that he and the hospital “do all they can to be sure their patients’ care is covered.”[161] Ms. Fitzgerald spent four nights at the hospital, received nine x-rays, two MRIs, scans of her carotid arteries and lungs, and a CT scan.[162] Her blood was drawn no less than six times.[163] When the hospital released her, her daughter was informed that the doctor’s recommendation, to admit Ms. Fitzgerald to an inpatient rehab center, would not be covered by Medicare because she was only an inpatient for one of the four nights.[164] Ms. Fitzgerald’s rehab cost was about $12,000 a month, which was paid out of pocket.[165]

Eighty-seven year-old Richard Keene was sent to a hospital by ambulance after severely injuring his back.[166] He laid in a hospital bed for three days, undergoing tests, eating hospital food, and receiving medication.[167] When he was ready to be transferred to a rehabilitation center, his family learned that he was classified as an outpatient because he was treated in an OU.[168] His family was shocked because he was treated like “a regular patient.”[169] Keene spent two months in a nursing home and his recovery cost him $24,339.[170] Medicare would have covered one hundred percent of his care for his first twenty days had he been admitted as an inpatient.[171]

Seventy-eight year-old retired Roberta Baxter was sent to the hospital when she dislocated her kneecap after a fall.[172] She spent four days at the hospital receiving treatment and subsequently seven weeks at a nursing home for rehabilitation to regain walking abilities.[173] She received a bill of $16,000 because Medicare denied her coverage since she was treated in the OU, even though she was certain that nobody told her that she was not admitted to the hospital during her stay.[174]

Some may say these are just anecdotal patient stories and anomalies in the traditional hospital setting. Unfortunately, multiple research studies in the public health sector are confirming this is a systemic problem in the US healthcare system.[175] The next section will highlight many of these studies and their disturbing results.

C. Research on Patient Outcomes After OU Placement Illustrates Increased Adverse Outcomes for Medicare Patients

A 2017 study analyzing the trends in use of OU for older Medicare Advantage (MA) patients showed a 133% increase from 2004 to 2014, while OU use for patients with commercial plans changed nominally during that time period.[176] Four independent studies looking into the mortality rate of patients thirty days after discharge from a hospitalization for heart failure illustrated a significant risk of death relative to earlier trends.[177] Because this increased mortality corresponded to CMS’s HRRP implementation, and heart failure was a targeted condition under the HRRP, many researchers believe that placement in the OU to avoid the HRRP readmission penalty could be to blame for the increased patient mortality.[178]

In addition, a 2017 study analyzing the health outcomes of patients after discharge from an OU found that:

[O]ne in five observation stays among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and over in the USA is followed by a hospital revisit within 30 days of discharge. These revisits result in inpatient care in 50% of cases and are increasing over time as observation services become more frequently used as an alternative to short stays in hospital. [179]

The study concluded that because revisit and mortality rates after discharge from observation stays closely paralleled outcomes after discharge from the ED, the results suggest that older adults discharged from observation stays are vulnerable to major adverse events at rates that closely parallel ED discharges.[180] In addition, the thirty day revisit rates are increasing in conjunction with the acuity of patients receiving observation services, which suggests that patients who are older and discharged from OUs will remain at risk for major adverse outcomes for the foreseeable future.[181] This grim outcome is especially likely in the Medicare population where beneficiaries are 20% more likely to require additional inpatient hospital care after discharge from an OU.[182] One factor that may be contributing to these revisit rates is that greater than 90% of these patients are discharged home.[183] This is likely caused by the fact that OU care does not qualify a patient for SNF coverage after discharge.[184] Thus, in order to avoid the large health care costs associated with SNF care, patients simply go home before they are physically capable and hope for the best.

IV. Measures Physicians and Hospitals Should Take to Ensure the Patient’s Autonomy and Best Interests are Prioritized when Placing a Patient in an OU

Thus far, this Article has discussed the problematic financial implications that arise from inappropriate use of OUs. In short, the most fundamental issue is that the unchecked conflicting financial interests between Medicare, providers, and patients ultimately end with poor quality of patient care and leave Medicare patients with unexpected and high medical bills.[185] The final step to ensuring the ethical use of OUs is understanding how to apply an ethical framework for patient placement determinations within a hospital. As the gatekeepers for patient placement,[186] healthcare providers have an ethical and fiduciary duty to put the best interests of the patient above their own or those of the healthcare institution.[187]

This ethical framework begins by analyzing the four most commonly referenced principles of biomedical ethics by Beauchamp and Childress (B&C): (1) respect for autonomy, (2) non-maleficence, (3) beneficence, and (4) justice.[188] This Part describes what these principles mean and explains how they should be applied when determining placement of patients in OUs. Additionally, this section will discuss Bernard Lo’s principle of “avoiding deception” and how this ethical principle is brought into question when a hospital utilization review committee determines the physician’s decision to admit the patient should be changed after the patient was formally admitted.

A. Respect for Autonomy Implies the Need for Informed Consent and the Avoidance of Deception

The first B&C principle is respect for patient autonomy, which can be defined as “a norm respecting and supporting autonomous decisions.”[189] B&C contend that “[r]espect for autonomy obligates professionals in health care . . . to disclose information, to probe for and ensure understanding and voluntariness, and to foster adequate decision making.”[190] In the clinical medical setting, it is often referred to as one’s obligation to respect the decisions made by adults with decision-making capacity.[191] Implicit in this obligation to respect a person’s autonomy is the duty to avoid deception and to keep promises.[192] Unfortunately, the financial conflict of interest described in this Article has created challenges in meeting this principle.

First and foremost, there is a lack of clarity provided to patients on the implications of being placed in an OU, despite written and oral notices mandated by CMS or each state’s department of health.[193] For example, the New York State Department of Health states that “written and oral notice must be provided to the patient or the patient representative” informing them that the patient is not being admitted to the hospital and such notice must also include “a statement that [OU] status may affect the person’s Medicare, Medicaid[,] or private insurance coverage for the current hospital services, including medications…, as well as coverage for any subsequent discharge to a skilled nursing facility or home and community based care.”[194] The notice must also encourage patients to seek further clarification with regards to coverage from their insurance provider.[195] Additionally, the “hospital must make a good faith effort to obtain written acknowledgement of [such] notice.”[196]

CMS requires the disclosure to be made using the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice (MOON) form.[197] The form requires the provider to list the patient’s name, the patient’s ID number, and the statement, “You’re a hospital outpatient receiving observation services. You are not an inpatient because…”[198] The provider must then specify the reason why the patient is an outpatient rather than an inpatient.[199] The form informs the patient that services provided while in an OU are considered outpatient services and are covered under Medicare Part B.[200] The form further states that for Part B services, the patient will generally pay a copayment for each outpatient hospital service provided (i.e., x-rays, labs, etc.) and 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for most doctor services, after the Part B deductible is met.[201] It describes how observation services may affect coverage and payment of care for SNF, after the patient leaves the hospital.[202] Under this section, the form attempts to explain the 3-day rule for SNF coverage.[203] Finally, the form mentions that the patient may be financially responsible for medications administered to them while they are in the OU and attempts to distinguish between “self-administered drugs” and drugs that must be administered by the hospital staff.[204] But it concludes by saying that most hospitals will not let patients administer even the “self-administered drugs.”[205]

While the language included on the forms provides general notice of the patient’s financial responsibilities, there is no mechanism to ensure the patient actually understands what the language means.[206] First, while section 400.3.7 of the Medicare Rules requires hospitals that receive federal financial assistance to provide language assistance services, there is no mention of the patient’s guaranteed right to a free translator on the MOON form.[207]

Second, it is highly confusing to patients to read a form that states they are considered outpatients, when everything the patients are physically experiencing would lead them to conclude they are an inpatient.[208] For example, a patient that is admitted to the hospital from the ED is brought either by bed or wheelchair by hospital staff to another unit in the hospital where they are assigned a room and are cared for by hospital nurses and physicians (i.e., hospitalists), similarly, a patient that is placed in an OU is transferred from the ED either by bed or wheelchair by hospital staff to another area of the hospital where they are assigned a room and are cared for by hospital nurses and likely a hospitalist. From the perspective of the average person, there is no difference in the care being rendered or the resources being utilized, so it is highly unlikely they would fully understand what it means when the form states they are being treated as an outpatient.[209] J. Stuart Showalter acknowledges this perception in his book “The Law of Healthcare Administration” by saying, “[s]ome outpatients—such as those occupying a bed for observation purposes or ambulatory surgery—may appear indistinguishable from those who are technically ‘inpatients.’”[210] The mere existence of notices such as these does not mean patients understand what ramifications OU status has with regards to their care and financial responsibility.[211] This leads to the important question of whether the patient is able to give true, valid informed consent in this instance.[212] According to B&C, “[a] person gives informed consent to an intervention if (and perhaps only if) he or she is competent to act, receives a thorough disclosure, comprehends the disclosure, acts voluntarily, and consents to the intervention.”[213] Jonsen, Siegler and Winslade, argue that “[b]ecause patients now bear an increasing portion of costs as co-payments and deductibles, they have a right to be informed about the expected costs of medicines, tests, procedures, and hospital admissions.”[214]

In the context of placement in an OU, valid informed consent would require a thorough and comprehensible discussion in the language spoken by the patient regarding the patient’s financial responsibilities and health benefits and risks of both options, admission to the hospital or placement in the OU.[215] If an alternative treatment option exists, for example being transferred to another hospital if inpatient bed availability is an issue, this should be disclosed as well.[216] Finally, the provider should discuss the consequences of the patient’s refusal to continue care—leaving against medical advice (AMA).[217] Ultimately, without a full understanding on the part of the patient of all of the above, informed consent and ultimately respect for the patient’s autonomy, cannot be achieved.

In addition, most patients are unaware that there are financial incentives for Medicare and providers to place patients in OUs, as discussed in Part II of this Article.[218] These incentives pose a high potential for a financial conflict of interest for the hospital and the provider.[219] As B&C proposed:

The degree or level of risk [from a conflict of interest] depends on (1) the probability that the professional’s personal interests will have an undue influence on his or her judgments, decisions, or actions, and (2) the magnitude of harm that may occur as a result. Even if the circumstance of conflict does not in fact bias the individual’s judgment, and even if no wrong is committed, it is still a conflict-of-interest situation that makes it reasonable to suppose that tainted judgments might occur and to require that they be disclosed, mitigated, managed, or avoided altogether.[220]

As the California Supreme Court held in Moore v. Regents of the University of California,[221] “a physician must disclose personal interests unrelated to the patient’s health, whether research or economic, that may affect the physician’s professional judgment.”[222] Thus, this Article argues that valid informed consent to OU status requires the disclosure of these financial incentives.

Finally, and most importantly, informed consent must be sought before any treatment is offered to the patient.[223] Medicare requires providers to present the patient with the MOON disclosure no later than 36 hours after observation begins or sooner if the patient is admitted, transferred, or released.[224] However, this time frame does little to protect the patient from the potential financial burden that OU care places on him or her.[225] As mentioned previously, OU care is billed as an outpatient service and therefore patients are responsible for a 20% copayment of all fee-for-service care they receive.[226] In addition, Medicare will not pay for medications given to OU patients which the patient could self-administer.[227] As a result, the pharmacy charges for providing a patient with medication in the OU is passed directly to the patient.[228] Lastly, time spent in the OU does not count towards the Medicare 3-day rule and as a result, a patient who requires skilled nursing care following discharge from the OU is financially responsible for the entire cost of such care.[229] A disclosure that takes place after the patient is already placed in an OU does little to enable the patient to make responsible financial decisions regarding his or her care.[230]

Even more disruptive to the patient’s autonomy is when a utilization review committee determines that the physician’s order admitting a patient for inpatient services should be changed post admission and requires the physician change the patient’s official status to outpatient with no input from the patient or the patient’s family. This unilateral decision-making on the part of the hospital and physician runs completely contrary to the doctrine of informed consent and the ethical principle of respect for the patient. Additionally, this change in patient status without first seeking the patient’s agreement could be construed as deceptive and run afoul of B&C’s and Lo’s principle of avoiding deception.[231] Ultimately, when physicians defer to the decisions of the utilization and review committee without patient input, it leaves the patient with no voice and no recourse when faced with the financial consequences of this decision.[232]

While the institution’s ability to get paid should not factor into patient care from an ethical perspective, a patient should be given the opportunity to consider the acceptability of the cost of care and the impact the cost will have on the patient and/or the patient’s family.[233] A more ethical disclosure, one which respects the patient’s autonomy, would: occur at the time the decision of whether to admit the patient or place the patient in an OU is being made; clearly state the potential financial conflict of interest the hospital has in terms of Medicare reimbursement; require a fee breakdown of services the hospital anticipates will be provided to the patient based on the patient’s symptoms and initial diagnosis;[234] provide the patient with a clear understanding of what care he or she would receive either as an inpatient or an OU patient; and once a patient is formally admitted to the hospital[235] any subsequent change to outpatient status would require formal written consent by the patient before the change becomes legally effective. This would allow the patient to play an active role in the decision-making process for his or her care.

B. Non-maleficence Requires Physicians to Consider How Barriers to Care Negatively Impact the Patient’s Health

The second B&C principle is non-maleficence, defined as “a norm of avoiding the causation of harm.”[236] Under this principle, providers ought to abstain from any action that will cause harm to patients.[237] This also includes obligations not to impose risks of harm upon patients.[238] According to B&C, “[a] person can harm or place another person at risk without malicious or harmful intent.”[239] Specifically, in cases of risk imposition, “both law and morality recognize a standard of due care that determines whether the agent who is causally responsible for the risk is legally or morally responsible as well.”[240] B&C define due care as “taking appropriate care to avoid causing harm, as the circumstances demand of a reasonable and prudent person.”[241] This requires the provider to justify the foreseeable risks by the goals he or she hopes to achieve.[242]

In the context of OU care, the pursued goal is continued monitoring of the patient in a controlled environment until the medical provider can be sure the patient is not suffering from a condition that needs higher acuity treatment.[243] If utilized correctly, the intended benefits of OU use are lower medical bills for the patient and avoiding the premature discharge of patients in a health crisis.[244] However, the inappropriate use of OUs can actually cause more harm than good.[245] As previously established in Part III, studies have shown an increase in post-discharge mortality for Medicare patients previously hospitalized for heart failure and pneumonia, who subsequently presented to the ED within thirty days, but instead of being readmitted remained in the ED or were sent to an OU.[246]

Additionally, time spent in an OU or in the ED prior to (or in lieu of) an inpatient admission to the hospital does not count toward the 3-day qualifying inpatient hospital stay necessary for Medicare to cover care at a SNF.[247] For patients who spend the first 24 to 48 hours in an OU and who are later admitted to the hospital but then discharged within three days of their admission, they will not qualify for Medicare coverage in a SNF post-discharge.[248] This lack of coverage can cause the patient to refuse necessary skilled nursing care due to the prohibitively high costs of such care.[249] This consideration is especially vital for elderly patients who lack a sufficient support system at home.[250]

Finally, if the patient has multiple comorbidities and an established healthcare team knowledgeable about the patient’s health history, ordering the patient to be placed in an OU instead of admitted to the hospital may create a barrier to continuity of care.[251] Patients in the OU are typically cared for by ED physicians or hospitalists; providers who are unfamiliar with the patient’s medical history.[252] Observational and experimental studies indicate that greater continuity in the physician-patient relationship results in better patient outcomes.[253] Unfortunately, patients who are hospitalized frequently and suffer from a combination of chronic medical problems and social comorbidities are not well served by the hospitalist model of care since any given hospitalist does not adequately appreciate a patient’s medical history or changes in his or her condition.[254] Thus, when a patient with multiple chronic conditions lacks access to his or her dedicated healthcare team, this places the patient at increased risk of potential harm due to misdiagnosis and/or failure to treat.[255]

C. Beneficence Requires Physicians and Hospitals to Put the Best Interests of the Patient Before the Financial Interests of the Hospital

The third B&C principle is beneficence, “a group of norms pertaining to relieving, lessening or preventing harm and providing benefits and balancing benefits against risks and costs.”[256] This principle requires providers to act in the best interest of the patient.[257] In the context of an OU, the best interest of the patient is served by providing quality health care, ensuring continuity of care across different providers and facilities, and minimizing the patient’s financial burden.[258]

1. OU use is in the patient’s best interest when it promotes quality health care, allows for continuity of care, and minimizes the patient’s financial burden

As discussed in Part I, the best practice for providing quality health care in an OU is when the OU is either located immediately adjacent to the ED and is staffed by an emergency medicine physician–Type I OU, or if in a Type IV OU, placement is limited to a discrete set of symptoms and diagnoses. These practices serve the patient’s best interests because in Type I OUs, emergency physicians are specifically trained to diagnose medical problems and to handle acute medical crises, and in Type IV OUs limited to a discrete set of diagnoses, nurses and physicians are able to develop a standardized, systematic approach to patient care, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the care.[259] As a result, physicians considering whether OU placement is in the patient’s best interest should utilize the inclusion and exclusion criteria discussed in Part I and be cautious of placing patients in Type IV OUs when the OU is not staffed by providers who are specifically trained to manage a discrete set of diagnoses.

OU status may also be in the patient’s best interest when it allows for continuity in the patient’s care.[260] Continuity of care is best achieved in either one of two ways: (1) when the OU is staffed by personnel from the hospital’s ED, such as in a Type I OU;[261] or (2) when OU placement is limited to a discrete set of symptoms or diagnoses if utilizing a Type IV OU. By utilizing the same ED staff in the Type I OU, the ED providers are better able to further the patient’s health history and ensure a greater understanding of the patient’s evolving medical condition.[262] In Type IV OUs, continuity is achieved through the perspective of the provider rather than the patient. Properly run, protocol-driven Type IV OUs utilize a highly specialized trained team of professionals who are well-versed in how to manage a discrete set of symptoms and diagnoses.[263] Thus, the continuity stems more from consistently dealing with the same disease process rather than the individual patient.

OU status may also be in the patient’s best interests financially if the patient’s condition is too uncertain to allow for discharge home, but not serious enough or still of an unknown nature so that admission to the hospital may result in an undue financial burden on the patient.[264] This could happen when the Medicare Part A deductible is greater than any Medicare Part B contributions billable to the patient.[265] Studies show patients with presenting symptoms or diagnoses of chest pain, asthma exacerbation, and heart failure exacerbation receive effective, quality care at a lower cost in an OU rather than being admitted as an inpatient.[266]

2. OU use is not in the patient’s best interests when the protocols for OU placement have suffered from “OU creep” or when being utilized for patients with chronic medical problems and other medical comorbidities

When OUs are set up in a separate area of the hospital, such as many Type IV OUs, and are not managed by a care team specialized in treating a discrete set of diagnoses, the quality of care patients receive is jeopardized.[267] Unfortunately, since the creation of OUs, many hospitals have expanded OU use to include almost any condition that case managers opine can be managed over a short period of time.[268] This expanded use of OUs, also known as “OU creep,” jeopardizes the ability of providers to offer specialized care.[269] Furthermore, studies show that an additional transfer to another location with different medical providers when not absolutely necessary increases the risks associated with communication errors during nursing and physician staff hand-off, physician and medication orders, and patient transport.[270]

In addition, for older patients who are hospitalized frequently and suffer from a combination of chronic medical problems and medical comorbidities, the OU is often not the best placement choice.[271] As discussed in Part I, exclusionary criteria for OU placement includes conditions in older adults where there is a likely need for placement in a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility, failure to thrive, exacerbation of chronic problems, inability to ambulate, altered mental status, and a projected length of stay of greater than 24 hours.[272] These are key exclusionary criteria because Medicare will only cover SNF care after a patient has been an inpatient for three consecutive days and OU care does not count towards the three-day requirement.[273] Therefore, placing older patients with the above medical issues in an OU may inhibit their ability to pay for SNF care thereby jeopardizing the continuity of their care through the spectrum of healthcare services they require.[274]

3. Four questions to consider when determining whether placement in an OU is in the patient’s best interest

In analyzing what course of action is in the best interest of the patient, this Article argues that four questions should be considered. First, what “type” of OU does your facility utilize? Second, do the patient’s presenting symptoms align with exclusion and inclusion criteria that support the use of OUs in terms of efficiency and quality of care? Third, does placement in the OU achieve the desired continuity of care for the patient during the diagnosis stage? And fourth, is the patient otherwise healthy or does the patient have multiple comorbid medical conditions? It is important to note, that even among these four considerations, the principle of beneficence requires balancing benefits against risks and costs, and then deciding whether it is in the best interest of the patient to be placed in an OU.

D. Justice Requires Physicians to Make Decisions on a Patient’s Placement in the OU based on Greatest Benefits for the Overall Population of Patient Receiving Care

The final B&C principle is justice.[275] This principle can be defined as “a cluster of norms for fairly distributing benefits, risks and costs.”[276] According to B&C, “[a]s a matter of human rights, all citizens in a political state should have equal political rights, equal access to public services, and equal treatment under the law. . .”[277] B&C extend this principle into the healthcare setting by arguing that justice in health care requires that delivery of programs and services should be made available to all members of a specific class.[278] B&C acknowledge that there may be situations in which equal access to health care is impossible and rationing may need to take place, and when this happens, “even valid principles of justice may be justifiably infringed, compromised, or sacrificed.”[279] But how does one recognize when a person’s right to access a resource may be infringed? Under what circumstances is it ethically permissible to not treat patients equally?

According to Lo, when considering whether to ration care in the health care context, allocating resources is more strongly justified when three conditions are met: (1) the saved resources would be allocated to interventions that provide greater benefits for the population of patients receiving care; (2) the physicians would not benefit directly from saving resources; and (3) the limitations in care are applied to all similar patients with no exceptions based on privileged social status.[280] In the context of patient placement in an OU versus admission to an inpatient bed, shouldn’t all patients presenting to the hospital for care be treated equally? If so, why has research shown a disproportionate number of Medicare patients being placed in OUs versus patients with commercial insurance plans?[281] Is it in keeping with the principle of justice to allow insurance type to dictate the care a patient receives? Before attempting to answer this question, one must examine whether there is even a situation in which the rationing of resources allows for the infringement on a class of people’s rights.

As Lo pointed out, in order to even consider rationing resources, there needs to be a scarce resource at issue.[282] Arguably, there are times when EDs have more patients requiring urgent care than the beds to house them.[283] In these situations, rationing ED beds is acceptable so long as Lo’s first principle is applied—ED beds would be allocated to patients with acute, critical conditions who would receive the greatest benefit from remaining in the ED, and patients who are stable but require further monitoring be transferred to an inpatient bed or an OU.[284] Rationing ED beds is justified in this scenario because it provides the greatest benefit to the patients who are in crisis and the limitations on access to the ED beds for the transferred patients is based on their medical symptoms and diagnoses with no exceptions based on privileged social status or insurance type.[285]

Justice becomes an issue when we examine why some patients are transferred to an inpatient bed while others are placed in an outpatient OU bed. In most situations, aside from the recent Covid-19 pandemic, there are sufficient inpatient beds to house patients who are not stable enough to be discharged home, so there is no scarce resource issue at play to justify treating similar patients differently.[286] As Lo’s third condition highlights, it is unethical to place the interests of some patients over others.[287] In the context of OU placement, patients should be evaluated for inpatient versus OU status based on their medical conditions, not on their payor status. This means a patient’s insurance status (i.e., private insurance, Medicare, or uninsured) should have no bearing on whether the patient is admitted as an inpatient or placed in an OU.

Unfortunately, as the Alexander v. Azar case and recent research illustrates, insurance status does impact patient placement.[288] Part IV of this Article highlighted a 2017 study that showed an increased preference for OU use in Medicare Advantage patients over younger patients with commercial plans.[289] Additionally, four independent studies correlated an increased mortality for Medicare patients thirty days after discharge from a hospitalization for heart failure after CMS’s HRRP implementation.[290] Researchers concluded that the desire to avoid the HRRP readmission penalty may have played a role in patient placement in an OU.[291]

When a group or class of patients are more likely to be put in an OU for the purpose of increasing insurance reimbursement or avoiding a financial penalty, it is the opposite of “fairly distributing benefits, risks and costs” as defined by B&C.[292] Therefore, applying the ethical principle of justice to OU utilization requires that patient placement decisions be based on what is best for the patient’s health, not on financial factors.[293]

One might argue that with limited financial resources, Medicare is justified in incentivizing the most efficient way of spending its money. Medicare benefits from incentivizing the use of OUs by placing some financial burden on patients and thereby reducing amounts payable by itself.[294] For example, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that payments in 2012 made by Medicare in reimbursing hospitals were significantly less for short observation units, at an average of $1,741, while brief inpatient visits had an average payment of $5,142, demonstrating Medicare’s financial incentive to motivate providers to place patients in OUs.[295] However, from an ethical point of view, if a patient is placed in an OU purely to reduce the financial burden of Medicare or increase the reimbursement potential of the facility, and has no positive effect or even a deleterious effect on the quality of care provided to the patient, it violates Lo’s second condition because Medicare and/or the facility is directly benefiting from saving the resource (hospital inpatient beds).[296]

This Part has highlighted how B&C’s four principles of biomedical ethics—respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice and Lo’s concepts of avoiding deception and parameters for resource allocation—can be used in a general sense to determine whether placement in an OU is done ethically. The next Part will utilize a patient case study to illustrate how utilizing the four-box approach to clinical medical ethics created by Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade can help healthcare providers and institutions ensure that patient placement in OUs respects B&C’s four ethical principles.

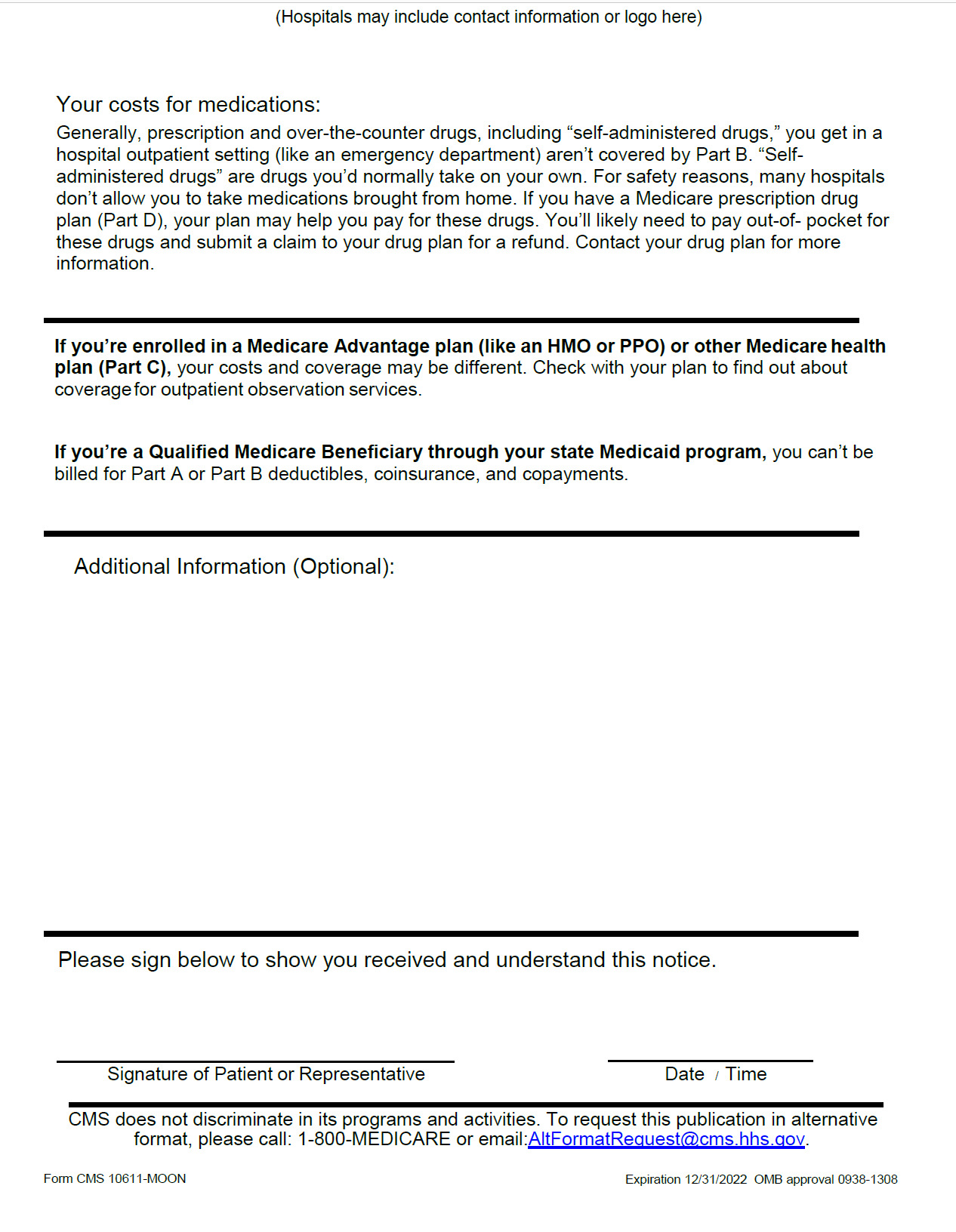

V. Using the Jonson, Siegler, and Winslade Four-Box Approach to Ethically Determine Patient Placement in a Hospital

Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade breakdown decision-making in clinical medical ethics into four boxes or categories: (1) medical indications; (2) preferences of the patient; (3) quality of life; and (4) contextual features.[297] Each presents a list of questions aimed at assisting medical providers to make ethical decisions in a clinical setting.[298] Within each of these categories is housed one or more of the B&C ethical principles.[299] For example, when analyzing the medical indications for the patient, a provider should keep in mind the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence.[300] Within the category of patient preferences, a provider should consider respect for the patient’s autonomy.[301] Under the category of quality of life, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and respect for autonomy should be weighed.[302] Finally, within the category of contextual features, providers should give deference to the ethical principles of justice and fairness.[303] For the purposes of this analysis, the questions in italics have been added to the lists in order to focus the analysis on the ethical use of observation care.

A. How to Apply the Four-Box Approach to Patient Placement Decisions

Let’s apply the four-box approach to the following patient case:

A 71-year-old woman presents to an ED complaining of severe lower left flank pain. The patient is complaining of nausea. Patient has no dysuria, hematuria, or fever. The site of the pain is red, but no cellulitis is present.

The patient has a past medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, myotonic dystrophy stage 2, multiple previous infections including MRSA bacteremia requiring hospitalization and IV antibiotics, a stage IV decubitus ulcer on her coccyx, and a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the common femoral vein. The patient is on numerous medications to treat her multiple chronic diseases. The patient has a concierge primary care physician who has managed her care during her previous hospital admissions.

The ED physician suspects a possible urinary tract infection (UTI) and orders a urinalysis. The results of the urinalysis are inconclusive, so a straight catheter urinalysis is done which shows trace leukocytes. A urine culture is ordered and sent out. A complete blood count (CBC) drawn on the patient shows an elevated white blood cell count (WBC) of 18.5 and a C-reactive protein level (CRP) of 301.3. While waiting for the results of the urine culture, the ED staff investigates possible admission to the hospital. The teaching service states it is no longer accepting patients, so the ED case manager considers placement in the hospital OU. The hospital OU is located in a separate unit of the hospital and manned by a hospitalist and nursing staff.

1. Box 1—Medical Indications

When analyzing the medical indications, providers must conduct a beneficence and nonmaleficence analysis to determine the best course of action for the patient’s medical care.[304] The relevant four-box approach questions when addressing the medical indications for this fact pattern are:

-

What is the patient’s medical problem? Is the problem acute? Chronic? Critical? Reversible? Emergent? Terminal?

a. Is the patient otherwise healthy or does the patient have multiple chronic medical conditions?[305]

-

What are the goals of treatment?

-

In what circumstances are medical treatments not indicated?

-

What are the probabilities of success of various treatment options?

a. Does placement in the OU achieve the desired continuity of care for the patient during the diagnosis stage?[306]

-

In sum, how can this patient be benefited by medical and nursing care, and how can harm be avoided?

a. Do the patient’s presenting symptoms align with exclusion and inclusion criteria that support the use of OUs in terms of efficiency and quality of care?[307]