Introduction

Extensive attention has been placed on preventing the spread of COVID-19. Mandates nationwide have limited person-to-person contact in a collective effort to minimize the frequency of new cases. In stark contrast to the pervasive focus directed toward instituting safe practices throughout the country, those in the federal prison system have effectively been overlooked. Overcrowding, unsanitary conditions in prisons, and systemic ambivalence regarding the health concerns of prisoners are largely responsible for the ease by which COVID-19 can spread.[1] In response to the impact of COVID-19 on national health and economic downturn, Congress passed the CARES Act, which in part allocated $100 million in funds to the federal prison system in order to quell the spread of the deadly virus within penitentiaries.[2] Regardless, prisoners are infected by, and die from COVID-19 at a considerably higher level than individuals in the general public.[3] To exacerbate this already pressing issue, all medical costs for incarcerated prisoners in federal institutions are paid for by the federal government.[4] Additional funding by way of the CARES Act is certainly a step toward handling the virus in prisons, but medical treatment and vaccination is largely reactive. A proactive approach to dealing with the spread of pandemics like COVID-19 exists in the form of “compassionate release.”[5]

Since statutory inception, prisoners have sought compassionate release under 18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A) that would reduce sentences for “extraordinary and compelling reasons.”[6] However, prisoners were very rarely granted compassionate release.[7] Formerly, a prisoner would move for the Bureau of Prisons (the Bureau) to consider his or her application; should the Bureau approve the application, it would submit to the courts a motion to grant the sentence commutation; however, the Bureau rarely approved these motions. The First Step Act was signed into law in 2018, which removed the requirement to appeal to the Bureau, and instead allowed inmates to appeal directly to the courts.[8] Though, historically, compassionate release has been under-utilized because of the Bureau’s role as gatekeeper, it has gained more attention with the advent and spread of COVID-19 in correctional facilities; legislative changes meant that prisoners could now bypass the Bureau approval by utilizing provisions in the First Step Act.[9] A growing number of prisoners have begun to seek sentence reductions because of pre-existing illnesses that might make them particularly susceptible to the harsh effects of COVID-19.[10] This increased attention, however, has done little to control the spread of the virus in the penal system and healthy individuals have little to no recourse for seeking sentence commutations.

To effectively curb the consequences of COVID-19 and future novel deadly infectious diseases in prisons, it may be prudent to lessen the degree to which the Bureau or courts consider reasons for release to be “extraordinary and compelling.” Traditionally, courts consider factors in 18 U.S.C § 3553 that make an individual eligible for compassionate release under § 3582(c)(1)(A).[11] However, certain amendments may reduce the degree to which justices scrutinize applications, in turn helping to reduce the spread of COVID in prisons. As it stands, the significant potential for an inmate’s contracting an illness that would likely result in serious health concerns is not an extraordinary and compelling reason for compassionate release.[12] Amending the provision of the existing illness requirement to include a serious potential for contracting a debilitating disease may prove to be crucial in combatting the ever-growing numbers of COVID-positive inmates. Allowing, to a wider extent, the early release of elderly, well-behaved inmates with low rates of recidivism, who have served a considerable amount of their sentences would remove from the penal system a particularly susceptible class that could easily contract and transmit diseases like COVID-19. Reviewing courts may thus consider the potential affects, as opposed to the manifest health problems that a disease such as COVID-19 might have on especially susceptible elderly inmates.

Further, it may be appropriate to expel the exhaustion requirement in § 3582 that requires inmates to first exhaust all avenues for compassionate release motions, prior to appealing to courts. Such a requirement, based on its text, is a high bar for healthy elderly inmates to reach. Finally, there might be a remedy in the form of an automated appeals process, which effectively allows prisoners to move for compassionate release, without requiring the Bureau to have to directly deliberate individual cases. Such a measure would remove the pressure of a rise in reduction of sentence claims on the Bureau, by granting automatic approval to residents of prisons who fall into a particularly susceptible class of individuals. The proposed fixes in this paper may prove to be particularly cost-effective moves for the federal penal system. Making it easier for prisoners to move for early release could help remove individuals with extenuating medical history, thereby reducing the costs of medical care.

These considerations are important to address from a policy standpoint. In providing prisoners an easier way to seek commuted sentences, it is important to keep in mind the reasons these individuals were incarcerated to begin with. Such a consideration requires a deeper look at the justification for the penal system. Part I of this paper briefly reflects upon the purpose of the American penal system, inherent problems therein, and the ultimate effects those problems have had on prisoner health. Part II examines the effects of COVID-19 on the general public and within the prison system. Part III addresses the role of vaccination within the prison system. Finally, Part IV considers the potential remedies for COVID-19 and future outbreaks of communicable disease that pose serious harm to prisoners.

I. The American Prison System

Modern prisons are not well-suited to prevent the spread of disease. This result is not the product of coincidence, but of circumstance. To better understand the health concerns of prisoners posed by the coronavirus (COVID-19), it is important to first discuss the history of the American prison system because the current state of affairs within prisons is a direct consequence of the approach to punishment for criminal conduct.

Two distinct rationales for criminal punishment exist to justify the American penological system. The utilitarian rationale justifies criminal punishment as a way to achieve “deterrence, rehabilitation, [and] incapacitation.”[13] This forward-looking approach punishes criminal conduct so that offenders are “deterred from committing future crimes; so that they will be rehabilitated and thus will not commit crimes in the future (upon release); so that they will be prevented from offending again.”[14] Utilitarian thinkers consider the benefit to society for punishment of offenders.[15]

The second approach is the backward-looking, retributive rationale for criminal punishment. In contrast with utilitarian thinkers, those in the retributive camp view incarceration as “just punishment for moral desert.”[16] Retributivism focuses not on the benefit to society for criminal punishment, but instead adopts the age-old adage, an eye for an eye.[17] Modern penology seems to have aligned with the retributive rationale, such that “punishment … is now acknowledged to be an inherently retributive practice.” [18] In keeping with the retributive theme, it seems that federal prisons have put prisoner welfare on the backburner.

Most prisons are constructed for the primary purpose of maximizing public safety, and not for the minimization of disease spreading.[19] Prisons often ration sanitization products in order to keep costs down.[20] The Bureau has responded to misinformation regarding its efforts to subdue the spread of COVID-19 such as issuing masks and adopting measures specifically designed to combat COVID-19.[21] Nevertheless, one federal prison came under fire when prison staff failed to abide by Bureau guidelines by neglecting to separate asymptomatic, COVID-19-positive inmates from the general population, instead letting the inmates share showers, telephones and other common areas with unaffected prisoners.[22] Though the Bureau might respond to criticism by implementing safer practices, this error casts a shadow on the federal penal system and reinforces the notion that prisoner welfare has not been one of the top priorities for Bureau institutions.

II. COVID-19 Within the Prison System

COVID-19 has had an unprecedented impact on nearly all aspects of life and is responsible for the deaths of many Americans. To slow the detrimental effects of COVID-19, states have responded by issuing mandates such as mask orders to diminish the spread of the disease in the general public.[23] By and large, the younger population is far less susceptible to severe illness from COVID-19.[24] However, this does not mean that they are not capable of transmitting the disease to individuals that are particularly susceptible to COVID-19. In fact, data suggests that young adults are to blame for high rates of positive COVID-19 tests, particularly in regions where the disease is most widespread:

During June–August, COVID-19 incidence was highest in persons aged 20–29 years, who accounted for >20% of all confirmed cases. The southern United States experienced regional outbreaks of COVID-19 in June. In these regions, increases in the percentage of positive SARS-CoV-2 test results among adults aged 20–39 years preceded increases among adults aged ≥60 years by an average of 8.7 days (range = 4–15 days), suggesting that younger adults likely contributed to community transmission of COVID-19.[25]

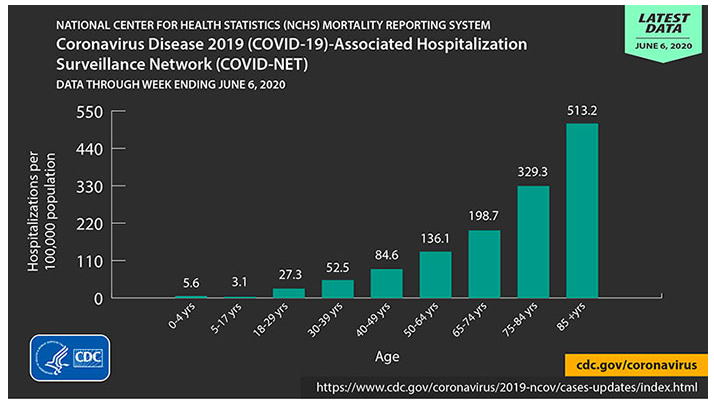

According to the CDC comparison of COVID-19 effects by age group, the elderly are far more susceptible to severe illness from contracting COVID-19, regardless of underlying medical conditions.[26]

To make matters worse, 80 percent of deaths caused by COVID-19 have been among individuals 65 years and older.[27] Juxtapose the national effort to soften the impact COVID-19 – often to proportionately little avail – with the historically grim conditions in penitentiaries wherein prisoners are routinely subjected to tight living quarters, overpopulation, and physical violence from other inmates.[28] Where free individuals might decide to distance themselves from others for purposes relating to health preservation, prisoners are denied that freedom by the inherent nature of federal prisons. The Bureau is not oblivious to the presence of COVID-19 in its facilities; it has issued modified operations to help diminish the threat posed by COVID-19.[29] This statement of operations, however, offers no affirmative procedures to reduce overpopulation, and instead serves as a statement of changes to daily functions such as reduction in prisoner-prisoner contact, visiting hours, and the imposition of certain mandatory quarantine for incoming or outgoing prisoners.[30] The stark rise in prison populations since the 1970’s can be attributed to laws designed to punish repeat offenders.[31] In fact, “[t]he United States boasts the largest incarcerated population in the world.”[32]

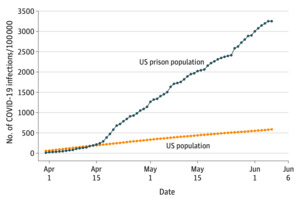

One in every 15 Americans have been infected with COVID-19.[33] The staff of Bureau facilities face a dramatic increase in exposure compared to the average American.[34] More than 3000 of the approximately 36 thousand the Bureau staff have recovered from COVID-19.[35] This statistic suggests that one in 12 Bureau staff have contracted COVID-19. Combining the alarmingly high rate of infection for Bureau staff with the national rate puts Bureau staff in a class among the most likely to contract COVID-19. The staff, unlike prison residents, leave their posts, go home to families, and interact with the general public. Failing to prevent the spread of COVID and other serious illnesses within prisons starkly contrasts with the Bureau’s congressionally delegated responsibilities. Due to conditions of confinement, prisoners are equally, if not more likely to contract COVID-19 than Bureau staff; overpopulation and systemic disregard for welfare is entirely antithetical to the national COVID-19 response. Incarcerated people are infected by the coronavirus at a rate five and a half times higher than the national rate.[36] Moreover, the death rate of inmates, at 39 deaths per 100,000 is higher than the national rate of 29 deaths per 100,000.[37]

There are economic considerations to account for in light of the COVID-19 epidemic. COVID-19 exposes the Bureau to unforeseen economic costs regarding medical care for its residents. Due to age, the elderly are more prone to development of serious medical complications resulting from COVID-19 contraction.[38] According to the Bureau, roughly three percent of all prisoners detained in federal penitentiaries are over the age of 65.[39] This number requires closer consideration. Partitioning prisoners into strict age groups ignores the inevitability that prisoners with longer sentences age into the aforementioned elderly class. It approaches cost as a function of current age statistics and disregards potential changes in discrete age groups of prisoners. This myopic approach potentially underestimates the Bureau’s future financial burdens.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) emphasized this error in a 2015 evaluation considering the Bureau’s financial costs for medical care of its inmates. OIG suggested that classification of older inmates into a fluid, “aging” population is preferable to a model that strictly defines age ranges because such an approach better anticipates actual healthcare costs.[40] OIG determined that the aging population – inmates roughly 50 years and older – constituted approximately 19 percent of those being detained in federal prisons; it is this group that receives the majority of medical care and should therefore be of consideration by the Bureau.[41] It can take this data and reallocate funds to better anticipate potential healthcare costs for the growing aging population, or it might look to other measures like compassionate release that are more cost effective. COVID-19 has presented the Bureau with a unique opportunity to respond to future public health crises.

Past Bureau budgets have a considerable pitfall – they do not anticipate the medical care for unforeseen medical emergencies like COVID-19.[42] To be fair, I don’t presume the Bureau could have reasonably anticipated a mass pandemic such as COVID-19, but, looking forward, it should be a serious point of concern. The cost of care for COVID-19 patients is not cheap by any stretch of the imagination. A study found that the national average cost for medical care for patients aged 51 to 60 presenting with COVID-19 was approximately $40,000.[43] In the general population, individuals may rely on a number of means by which to cover medical costs: they may choose to pay out of pocket or rely on government-funded programs or private insurance to assist with or cover the costs of medical care.[44] By contrast, the government is constitutionally responsible to cover the medical costs of prisoners it is charged with regulating.[45]

Thus COVID-19 and prospective outbreaks of a similar kind have the potential to be incredibly costly to the federal government. The United States Government Accountability Office cited a consistent upward trend in Bureau costs of medical care from the years 2009 to 2016.[46] This increase is attributed to the growing average age of individuals incarcerated in federal penitentiaries.[47] As the elderly prisoner population grows from year to year, so do the medical expenses the Bureau is required to account for in its yearly budget.[48]

Consider the trends in COVID-19 cases in the general public; even with public and private efforts to effectuate a decrease in cases, we have recently witnessed a dramatic surge in cases. With the advent of COVID-19, President Trump signed the CARES Act, which in part provided funding to federal prison systems in the amount of $100 million.[49] Though this is certainly useful to address the healthcare concerns for prisons, there is much that can be done to anticipate future breakouts of disease in federal penitentiaries. One approach is for Congress to allot additional funding to the Bureau for anticipation of future outbreaks of disease. Though the Bureau could use additional funding and direct it toward legitimate prison reform, I believe that the justification for congressional spending of the sort is unnecessary. The government might find more cost-effective means of fixing the problems posed by pandemics by markedly reducing prison populations. A means to such end exists in the form of sentence reduction.

Currently, there are two routes by which a prisoner might seek a commuted sentence: home confinement and reduction in sentence by compassionate release.[50] The first is by authorization of home confinement.[51] Former Attorney General William Barr pushed heavily for this mode of release as a means to prevent further spread of COVID-19 in prisons.[52] This memorandum exists independently from compassionate release and is effectively a notice to the Bureau to consider home confinement as a means by which to allow prisoners to fulfill the remainder of their sentences within the confines of their homes or in halfway houses. Given the history of compassionate release cases, it was unlikely that this memorandum would have any serious significance in helping quell the spread of COVID-19. In stark contrast, however, the Bureau has placed at least 20,228 prisoners in home confinement; as such, home confinement may have seriously ameliorated the potential consequences of the Bureau’s failure to act.[53]

The pitfall of the home confinement release method, however, is that it is a purely discretionary authorization that comes from the Director of the Bureau; there is no language in the CARES Act or the memorandum that hints at the potential for prisoners to appeal Bureau failure to grant home confinement.[54] It is important to note that the number of prisoners released on home confinement does not solve the problem of federal prison overcrowding.[55] The Bureau projected in 2020 it would be 15% overcrowded, which amounts to an excess of approximately 21 thousand prisoners above starting capacity.[56] Clearly, home confinement has its limitations. Apart from being limited by Bureau deference, the change in executive administration renders the future use of home confinement to reduce the number of prisoners unknown.

The less deferential route, compassionate release, removes from the Bureau the independent authority to determine the fate of a prisoner’s request for reduction in sentence.[57] First codified in 1987 during the Reagan administration, and later amended by the First Step Act, compassionate release extends the right to a prisoner to appeal the Bureau’s express denial or denial by inaction of his application for sentence reduction according to standards under §3553(a).[58] Originally, prisoners could move for compassionate release with Bureau approval, who had exclusive authority to pass on these motions to courts for deliberation.[59] As a direct result of this exclusive authority, the Bureau very rarely approved motions for compassionate release.[60]

Congress saw an issue with the Bureau inactivity and, in an effort to combat the continuing problem, passed the First Step Act in 2018 as a bipartisan effort to allow prisoners increased opportunities for their motions for release to be considered. The First Step Act removed from the Bureau the exclusive power to effectively kill motions for compassionate release, by allowing a prisoner to appeal her motion to a court, after he has “fully exhausted all administrative rights to appeal a failure of the Bureau of Prisons to bring a motion on [his] behalf or the lapse of 30 days from the receipt of such a request by the warden of [his] facility, whichever is earlier. . . .”).[61]

The court in United States v. Ebbers noted that the First Step Act indicated Congress’s intent to expand prisoner access to compassionate release, in response to decades of unilateral control by the Bureau over prisoner motions.[62] The court was quick to note, however, that despite the expanded reviewability of the Bureau denial or inaction regarding compassionate release claims, “Congress in fact only expanded access to the courts; it did not change the standard” by which courts review compassionate release claims."[63] In short, the strict requirements for compassionate release remain the same; all that has changed is that the exhaustion requirement gives prisoners another set of ears to hear their cases.

In essence, what prisoners gained was the exhaustion requirement, provided for in the First Step Act; the appealability of the Bureau decision, only after 30 days, if the Bureau does not act sooner.[64] Since the outbreak of COVID-19, courts of review have relied heavily upon the exhaustion provision in compassionate release appeals.[65] In many cases, courts dispose of cases, not on merits of individual motions, but because cases simply are not ripe for review, that either the Bureau has not issued a final decision regarding a compassionate release motion and that the 30 day waiting period has not yet expired.[66] In United States v. Raia, a prisoner appealed his denial of compassionate release.[67]

Though the court stated in dicta that the exhaustion requirement “presents a glaring roadblock foreclosing compassionate release” and that it anticipated the “statutory requirement will be speedily dispatched in cases like this,” the court nevertheless concluded that it lacked jurisdiction because Raia’s appeal did not strictly comply with the exhaustion requirement.[68] In United States v. Alam, the court went a step further to state that it would dismiss movant’s compassionate release appeal not because it lacked jurisdiction over the motion, but that the motion did not comply with the statutory exhaustion requirement.[69]

Incidents have surfaced that recount the trouble inmates have had moving for compassionate release. Consider the case of Saferia Johnson, a 36-year-old mother of two, who was serving a 46-month prison sentence. In contrast with Raia’s compassionate release case, after having petitioned for compassionate release due to complications arising from preexisting medical conditions, she was denied by the Bureau.[70] The denial thereby satisfied the requisite exhaustion of all possible means to seek compassionate release, which allowed her to appeal the denial to a court.[71] In the course of appealing the denial of her application, she contracted COVID-19, and quickly succumbed to the illness.[72] Johnson was the second female inmate at the detention center to die from COVID-19.[73] Though Johnson was among the younger population of inmates, the procedural hurdles she dealt with have been felt by many prisoners seeking relief.[74]

Despite positive prison reform, incarcerated individuals still have little success receiving favorable compassionate release outcomes.[75] Though data shows there has been an increase in the number of compassionate release motions granted, that number pales in comparison to the number of cases that are denied.[76]

Though federal prisons have seen a marked decrease in prison population, this is not likely due to an inversely proportionate rise in grants of sentence commutations due to compassionate release.[77] In all likelihood, this trend may be attributed to the aforementioned grants of home detention authorizations.[78] Early drops in prison numbers, predating wholesale home confinement authorization, may be attributable to national slowdowns in court proceedings, as a means to prevent further introduction of the virus into prisons, and as such are attributable to the courts and not to the Bureau.[79] According to the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC), there has been a marked decline in the number of incoming prisoners during the COVID-19 era.[80]

Therefore, one might argue that, despite the addition of the exhaustion requirement by way of the First Step Act, the Bureau still acts as the gatekeeper, at least for a time. “Under 18 USC 3582 (c) (1), an inmate may file a request for a reduction in sentence with the sentencing court after receiving a BP-11 response under subparagraph (a), the denial from the General Counsel under subparagraph (d), or the lapse of 30 days from the receipt of such a request by the Warden of the inmate’s facility, whichever is earlier.”[81]

For 30 days after the creation of a motion, the Bureau retains unilateral control of the process.[82] The Bureau director can fundamentally delay the entire process by choosing to turn a blind eye to all compassionate release applications. As in Raia, prisoners have sought relief from courts of appeal, where the Bureau has not yet made a final statement regarding the outcome of a motion for compassionate release, and, like Raia, they have been denied compassionate release motions due exclusively to failure to exhaust all remedies under § 3582(c)(1)(A), potentially disregarding the merits of the requests.[83] Inmates considered to have exhausted all forms of relief only if the Bureau does not act upon requests for reduction in sentence (RIS) within 30 days.[84]

There is a glaring problem in the current state of compassionate release procedure. Generally, 30 days may be considered a negligible time frame. However, considering the living conditions of prisons and the effects COVID-19 has had on Bureau facilities, the Bureau’s discretionary period may be of greater concern. In some cases, it might be enough time for a seemingly healthy individual to contract COVID-19 and ultimately fall victim to it. It might be pertinent to consider shortening or outright dispelling the exhaustion requirement, while retaining language from the First Step Act that grants prisoners the right to access courts of consideration.

COVID-19 does not seem to heed the arbitrary 30-day spell – why should prisoners have to wait? In the context of a global pandemic, the 30-day time frame seems like nothing more than an administrative formality that disregards potential effects that viruses like COVID-19 pose to correctional facilities. As discussed, the added time frame in the First Step Act exists to prevent the Bureau from unilaterally controlling prisoner access to courts when prisoners seek reductions in sentence by way of compassionate release.[85] COVID-19 complicates the process of appealing for commuted sentences because 30 days might very well be the difference between life and death for many inmates. According to the CDC, COVID-19 spreads through “respiratory droplets . . . produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks, or breathes.”[86] For the reasons discussed in Part I, this is of serious concern for prisoners, but the health concerns posed by contraction of COVID-19 are by no means limited to a class of incarcerated individuals.

As the United States struggled to halt the spread of the novel coronavirus, citizens of the United States started to succumb to a bevy of health concerns caused by COVID-19. In all too many cases, the virus contributed to the deaths of Americans.[87] COVID-19 infection can cause rapid health deterioration.[88] For example, an eighteen-year-old with no prior health concerns died from COVID-19 in December 2020, three days after hospitalization.[89] This example demonstrates how quickly a novel virus can be fatal; while this paper does not suppose that all prisoners should make RIS without delay, it certainly highlights the notion that 30 days is not a trivial length of time. Though Congress has not specifically provided an exception to the 30-day exhaustion, its inclusion of a 14-day period for terminally ill patients suggests that Congress has considered the timeliness of the Bureau’s processing of a compassionate release request in the interest of the terminal prisoner.

III. Role of Vaccination in Prisons

I began writing this paper prior to approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, but I felt it important to discuss them in the context of the prison system.[90] Subsequent sections pose potential solutions to the spread of disease in ways that would require changes to existing legislation or promulgation of new agency regulations. Vaccinations appear at face value to be a welcome alternative to any substantial legislative change. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)'s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research is charged with monitoring vaccine production at the experimental level so that “FDA’s rigorous scientific and regulatory processes are followed by those who pursue the development of vaccines.”[91] Subsequently, “FDA evaluates the data to determine whether the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine has been demonstrated and whether the manufacturing and facility information assure product quality and consistency.”[92] Vaccines introduce the infectious part of a virus into a living host without causing disease, so that the host forms the requisite antibodies that respond to viral antigens.[93]

Can vaccination serve as a valid alternative to legislative change? Depending on who answers the question, the answer might be in the affirmative. Vaccination of prisoners does not pose any considerable threat to the well-being of society. A vaccine keeps wrongdoers in prison and away from the population that stands to be harmed by dangerous individuals. Others of the same camp might view vaccination as a means to treat an immediate problem, but that ignores alternatives that might better serve society.

Issues arise when one begins to question the legality of compulsory vaccination programs. Fortunately, the United States has not been dealt more than a handful of episodes of widespread communicable diseases.[94] A minor drawback of this fortune is that there is not much case law on government authority to compel vaccination. The benchmark for determining constitutionality of state authority to enact compulsory vaccination legislation is Jacobson v. Massachusetts.[95] In this century-old precedent, the Supreme Court was called upon to consider whether vaccination for smallpox could be made mandatory by state statute.[96] The statute in question “require[d] and enforce[d]” vaccination for all Cambridge residents.[97] Henning Jacobson refused the smallpox vaccination, recalling a prior incident when administration of the vaccination caused him severe distress.[98] Justice Harlan concluded that it was well within the police power of the states to compel vaccination, even when there existed an alternative to vaccination that was not unreasonably intrusive, where the state has a sufficient interest in compelling government interest. Insofinding, Justice Harlan cited the importance of vaccination “as a means of protecting a community against smallpox.”[99] The Jacobson Court held that restrictions on personal liberty set forth by law “[w]ith justification that meets constitutional standards . . . does not violate the Constitution.”[100] There existed a sufficient interest of the “safety of the general public” and the statute “encroached on liberty only when necessary for the public health or safety.”[101] The Court recognized that vaccines might be individually harmful to people within a target population, but it “specifically rejected the idea of an exemption based on personal choice.”[102]

Jacobson has not since been overturned, but that does not mean the Court’s conclusion should receive absolute and unfettered discretion in modern courts. Since Harlan’s Jacobson opinion, the United States has dramatically changed. During the 20th century, there was a trend toward expansion of individual liberties, including rights to personal privacy, that simply were underdeveloped in 1905.[103] For this reason, Mariner suggests that determining the degree to which Jacobson extends to modern pandemics like COVID-19 requires consideration of the era from which Jacobson arose.[104] In 1905, infectious diseases were the “leading causes of death and public health programs were organized primarily at the state level.”[105] This meant that the state had a particularly heightened interest in suppressing the spread of infectious diseases like smallpox.[106] Further, certain federal institutions such as the FDA had yet to take form and hospitals were just in their infant stages; thus, states had limited tools with which to address communicable disease.[107] Responding in part to the atrocities of the Nazi Party during World War II and, to a degree the Civil Rights movement, individual liberty interests began to find newfound reverence in the courts.[108]

Subsequent Supreme Court opinions illustrate the Court’s growing support of individual liberty interests. Justice Brennan, writing for the court in Winston v. Lee, acknowledged the “Fourth Amendment is a vital safeguard of the right of the citizen to be free from unreasonable governmental intrusions into any area in which he has a reasonable expectation of privacy.”[109]

Citing Winston, the court in Maryland v. King determined that a buccal swab was not inherently unreasonable because such an act is “quick and painless” and “requires no surgical intrusion beneath the skin.”[110] The King court considered, primarily, the reasonableness of a buccal swab, balancing government interest with detainee right to privacy.[111] The Fourth Amendment guarantees that “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated . . . .”[112] In King, it appeared objectively reasonable to the court that such a search under the Fourth Amendment clearly did not reach a level of unreasonableness to find in favor of King.[113] The administration of a vaccine, on the other hand, contrasts starkly with a procedure like buccal swabbing, and instead appears more like bodily invasion in Winston.

Prior courts have ruled that individuals have individual liberty interest against unreasonable antipsychotic medication by state penitentiaries.[114] In Washington v. Harper, the Supreme Court found that prisoners possess “a significant liberty interest in avoiding the unwanted administration of antipsychotic drugs under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”[115] In the case of vaccine administration, however, individual rights might still be limited as in Jacobson. Where state infringement on constitutional guarantees exists, “[s]trict scrutiny requires the government to show that the regulation is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest, with narrowly tailored meaning that no less restrictive alternative would serve its purpose.”[116] Regarding federal authority to compel vaccination there is limited information. Congress cannot require states to pass mandatory vaccination laws because the “Supreme Court has interpreted the Tenth Amendment to prevent the federal government from commandeering or requiring state officers to carry out federal directives.”[117] Further, “federal statutes can also restrict federal authority with regard to public health regulations.”[118] The federal government has much less authority to initiate programs to compel vaccinations than what is afforded governments at state and local levels.

Prisoners of Bureau facilities can refuse the administration of vaccines.[119] In the Bureau’s COVID-19 Vaccine Guidance, prisoners may decline to receive the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, by submitting a declination form.[120] A prisoner might chose refuse a vaccination because of a traumatic experience as in Jacobson, but justification for declination is not required.[121] Bureau declination forms, including for COVID-19 vaccines, do not require a reasonable explanation for refusal; a prisoner must simply sign and date the form.[122] If prisoners retain the right to refuse medical care at the federal level, it becomes apparent that vaccination cannot be the ultimate answer for addressing diseases such as COVID-19. Though Jacobson has witnessed a reincarnation of sorts, its applicability to the COVID-19 dilemma rests primarily with the states’ police powers. Writing for the court, Harlan was tasked with determining the extent of the state’s police power, in regard to the limitations imposed upon them by the 14th amendment.[123] Federal prisons fall within the jurisdiction of the Bureau; therefore, lack police power to compel vaccination of federally incarcerated individuals.[124] Jacobson does not appear to extend to compulsory vaccination programs in federal prisons.

Regardless, overcrowding, unsanitary living conditions, and related concerns are not solved by vaccination. Vaccinations are the products of human interactions with novel viruses. We cannot predict the arrival of unforeseen viruses, precluding any proactive measures therefor. Vaccination is, thus, a largely reactive way to address public health crises.

Before the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines for COVID-19, the mumps vaccine was the swiftest to be developed, having taken only 4 years.[125] While 4 years may appear lengthy, it is certainly desirable over the average 10-15 year time frame for vaccine development.[126] Even given the rapidity that approved COVID vaccines were developed and are now being distributed, while in wait, more than 390,000 Americans died as a result of COVID-19 complications – 2059 of whom were residents or staff of correctional facilities.[127] Proactive measures for disease control in prisons, like compassionate release, do not require scientific studies to determine mode of transfer, genetic fingerprint, or identifying related comorbidities. Making it easier for prisoners to appeal courts for shorter sentences removes from the equation the delay inherent with development and administration of FDA-approved vaccination.

Reliance on vaccination alone to quell the spread of COVID-19 and similar contagions ignores the larger problems—characteristic of prison systems. Vaccination to address the growing problem of disease in prisons ignores the aforementioned, systemic issues central to the United States model of imprisonment. It ignores overcrowding, often substandard sanitary conditions, and indifference to prisoner welfare in exchange for a response to a disease that has already contaminated federal prisons to the degree where United States prisoners are of the most affected classes of individuals in the world. Of course, it is important to consider vaccination benefits, but COVID-19 is not likely the last time U.S. prisons will struggle with surges of novel viruses. Vaccination should not be viewed as an alternative to positive and lasting changes in the federal prison system, but as a tool to be used in conjunction with such changes.

IV. Potential Changes to Existing Law

A. Extraordinary and Compelling Circumstances

Compassionate release in its current form is granted only if the movant can show the existence of “extraordinary and compelling circumstances that could not have been foreseen by the court at the time of sentencing”.[128]

While extraordinary and compelling reasons previously required the precondition that applicants have underlying medical concerns, the First Step Act provides for new release based on age instead of serious medical conditions.[129] Under the new RIS avenue in the First Step Act, a healthy prisoner seeking a sentence commutation must fall into a very specific class of “[i]nmates . . . who are age 70 years or older and have served 30 years or more of their term of imprisonment.”[130] Understandably, this is a very high bar. Take, for example, a healthy 75-year-old male who, having served 29 years in prison, seeks compassionate release, citing the language in the First Step Act as his “extraordinary and compelling” circumstance for RIS. Strict compliance with the First Step Act suggests that he should not receive a reduction in sentence because he has not served the requisite 30 years. It appears that the current language prevents otherwise worthy inmates from seeking any form of sentence reduction (if home detention is a foregone option). A serious concern exists also in the form of undiagnosed illness. Elderly prisoners above the age of 70 with undiagnosed medical conditions might be particularly susceptible to COVID-19-related complications.[131] Nevertheless, these individuals might be categorically barred from successful RIS by sentencing courts.

There is evidence that with age comes a reduction in the degree of recidivism.[132] Elderly inmates belong to a class that poses little threat to the general public.[133] In a study conducted to determine the rate of recidivism of elderly inmates, of a number of prisoners dubbed the Unger Group was released from Maryland prisons, and subsequently observed. The Unger Group showed a recidivism rate of three percent.[134] This starkly contrasts with the rate of recidivism of approximately 40 percent among all age groups in Maryland prisons.[135]

The data obtained from studying the Unger Group suggests that, in lieu of the strict 30-year requirement, the Bureau might rely instead on a proportionality of the sentence standard, allowing elderly prisoners serving time for minor offenses the opportunity to appeal for reduced sentences.[136] Such an approach might preserve the government’s interest in protecting the public from dangerous individuals. Further, the language in the First Step Act implies that compassionate release exists, first and foremost, to allow elderly individuals the enhanced opportunity to seek reduced sentences. Expanding RIS access to the elderly would seem to only further Congress’s intent.

Such a change might invite criticism that lessening the 30-year requirement, or proposing any substantive changes that would widen access to compassionate release, ignores the primary purpose of compassionate release, which is to grant early release for elderly prisoners who are terminally ill.[137] Though this has historically been the case, new changes by way of the First Step Act suggest that advanced age can be a sufficient “extraordinary and compelling” circumstance.[138]

I would like to note that in the course of writing this paper, there was some intense debate regarding the currentness of the sentencing guidelines for compassionate release.[139] As it turns out, the ground upon which the “extraordinary and compelling circumstances” requirement rests is tenuous. The United States Sentencing Committee (USSC) is responsible for determining what constitutes “extraordinary and compelling,” however those factors have not been adjusted to reflect the language of the First Step Act.[140] In fact, § 1B1.13. Reduction in Term of Imprisonment Under 18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A) (Policy Statement) has been repealed by implication, because of the language of the First Step Act.[141]

In United States v. Jones, the court recognized that under current language from the USSC, “only the Director of the [Bureau] could seek a sentence reduction under the statute, on an inmate’s behalf. If the Director of the [Bureau] declined to do so, the defendant could not challenge that decision in federal court.”[142] With the passage of the First Step Act, new legislation “remove[d] sole authority from the Bureau of Prisons, imbuing judges with the ability to decide compassionate release motions if the Bureau of Prisons denies or defers the motion.”[143]

Additionally, many district courts have determined that the authority to grant sentence reduction according to a showing of extraordinary and compelling reasons rests with the reviewing court, because of the incongruency between the First Step Act and the outdated language in § 3553.[144] It appears then that existing guidelines for determining whether an inmate meets the threshold requirements for compassionate release necessitates immediate revision to the language of § 3553, to address the inconsistency with new law and to provide courts a firm legal foundation upon which to adjudicate during compassionate release appeals. These changes might justifiably include revisions to existing thresholds for “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances for the reasons discussed, supra.

B. The Exhaustion Requirement

A solution to the growing health concerns of prisoners during public health crises would be to expel the exhaustion requirement in §3582, requiring prisoners to exhaust all administrative remedies before they can access sentencing courts. The 30-day clock poses a serious threat to the health and safety of prisoners subject to harmful communicable diseases.[145] Under the First Step Act, the Bureau commissioner is responsible for considering the applications of all prisoners seeking compassionate release for sentence reductions.[146] As cases rise, so do requests for release, evidenced by the growing number of compassionate release appeals in district courts.[147] “Since the pandemic began, the federal courts have been inundated with Compassionate Release applications from attorneys seeking the immediate or early release of clients in custody.”[148] Logistically, this presents a problem – the Bureau can only hear so many cases. If it is unable or even unwilling to consider all cases, then prisoners inevitably sit in wait for their requests to be processed for up a period of up to 30 days.[149] Only when the Bureau deliberates, or upon 30 days after initiation of the request, has a prisoner exhausted all potential remedies that would entitle access to a sentencing court.[150] Extinguishing the exhaustion requirement would allow prisoners to immediately move for compassionate release in their respective sentencing courts. This modification may also relieve the Bureau of its burden to consider both requests for home detention and those for compassionate release.

In response to COVID-19, an increasing number of district courts have resolved the 30-day time frame should not stand in the way of prisoner access to the courts.[151] Writing for the court in United States v. Haney, Judge Rakoff stressed that “in the extraordinary circumstances now faced by prisoners as a result of the COVID-19 virus and its capacity to spread in swift and deadly fashion, the objective of meaningful and prompt judicial resolution is clearly best served by permitting [defendants] to seek relief before the 30-day period has elapsed.”[152] Though this is not the standard approach applied in all district courts, other courts are adopting similar approaches to the 30-day exhaustion requirement, opting to act in the best interests of prisoners seeking RIS instead of strict compliance to the 30-day clock.[153] The concerns expressed by this growing number of courts raises the notion that changes to the First Step Act 30-day clock might well be warranted. Such a change, however, is likely to meet opposition.

A potential counterargument for the dismissal of the exhaustion requirement is that such a change invites into the courts a flood of cases, many of which may be entirely frivolous – these frivolous requests would in turn gum up the judicial function of the sentencing courts. However, in its current form, the First Step Act doesn’t necessarily preclude this result. Even in the case of Bureau inaction, prisoners can directly appeal to sentencing courts after 30 days of submitting a BP-11 form to the Bureau.[154] Expelling the exhaustion requirement simply expedites the process be removing from the Bureau the concerning power of delay. Courts may still find themselves on the receiving end of frivolous motions, but revisions probably would not exacerbate the issue.

Another challenge that may arise is that adoption of the judicial dismissal of the exhaustion period breaches separation of powers considerations; that placing what is effectively total control to hear cases in the hands of the courts unnecessarily increases the courts’ powers and diminishes the executive power of the Bureau to “have charge of the management and regulation of all Federal penal and correctional institutions.”[155] In light of a global pandemic, however, such expansion of power may be an effective means to a desired end goal of preventing the spread of COVID-19.

The inherent problem with the exhaustion requirement is that by failing to respond to compassionate release claims, the Bureau can fulfill its congressionally defined roles by total inaction.[156] This is problematic from a policy perspective because it allows the Bureau to turn a blind eye to the concerns of prisoners. For practical considerations, this may appear to be a solution that grants prisoners access to the courts if the Bureau is overwhelmed, which may well be the case.

Deferring wholly to the Bureau has proven to problematic, considering the degree to which prisoners making good faith cases for compassionate release; continued deference will likely show the same trend.[157] In the alternative to throwing out the 30-day clock, it could be reduced. This would prompt the Bureau to put greater emphasis on reviewing motions for compassionate release; if motions are denied, amending the exhaustion requirement would not procedurally affect the existing measures. The trouble with reducing the 30-day requirement is that there is little evidence suggesting how much or how little the time frame should be altered to affect positive change. Congress has expedited the process for terminally ill prisoners, giving the Bureau a 14-day period to deny or approve requests.[158] However, period reduction for all prisoners to 14 days defeats the purpose of granting prioritization to terminal inmates who need immediate consideration of their requests. There has been resistance to the notion that the 30-day clock is problematic. At least one court has suggested that the Bureau has been sympathetic to the effects of COVID-19 and that “thirty days hardly rises to the level of an unreasonable or indefinite timeframe.”[159]

Until Congress acts, either to amend or respond to court dismissal of the 30-day period, there is likely to be jurisdictional split on the issue. Though the Haney court determined that bypassing the 30-day clock is an equitable action, founded on consideration of prisoner welfare, other courts emphatically dismiss the judicial reasoning.[160] In United States v. McIndoo, the court adopted an opposing approach to Haney, finding that the “[e]xhaustion provision of compassionate release statute, which requires a prisoner to wait 30 days from the warden’s receipt of a request for compassionate release to bring a motion requesting release in court, is mandatory and not subject to a judicially-created equitable exception.”[161] Considering the aforementioned decisions, it becomes all too apparent that courts do not act in unison regarding the relationship between the exhaustion requirement and COVID-19.

C. A Novel Alternative: Automated Request Portal

This paper has focused up to this point on potential changes to the existing language within the First Step Act. These changes address existing problems inherent in the prison setting and propose to effectuate more concerted, national responses to preventing the spread of communicable diseases like COVID-19. Another potential remedy may be to automate the process by which prisoners can access courts to more expeditiously move for compassionate release. This section poses a solution that does not necessitate change to existing language in the First Step Act. The Bureau might decide to adopt the proposed solution to more effectively carry out its congressionally designated roles.[162]

When the Bureau acts on behalf of a prisoner by moving for a sentencing court to consider compassionate release, it applies a distinct set of guidelines. The Bureau will first consider “whether the inmate’s release would pose a danger to the safety of any other person or the community.”[163] Several factors might be considered to make this determination: age, prisoner disposition, nature of the crime, etc. Required in these determinations is “careful review of each compassionate release request.”[164] Prior to this determination, a prisoner must cite “extraordinary or compelling circumstances” that justify early release.[165] RIS can include a terminal medical condition, where “consideration may be given to inmates who have been diagnosed with a terminal, incurable disease and whose life expectancy is eighteen (18) months or less, and/or has a disease or condition with an end-of-life trajectory under 18 USC § 3582(d)(1).”[166]

Where a prisoner is determined to suffer from a terminal illness, the Bureau has 14 days to submit the RIS to the appropriate sentencing court.[167] It appears that Congress intended for these terminal individuals to have quicker access to sentencing courts, because of the nature of the health conditions of these prisoners. Elderly patients with terminal illness have recently had success receiving RIS from courts, but illness alone is insufficient to qualify a prisoner for compassionate release.

The Bureau is tasked with considering any number of the following when presented with an RIS: (1) nature and circumstances of the inmate’s offense; (2) criminal history; (3) Comments from victims; (4) unresolved detainers; (5) supervised release violations; (6) institutional adjustment; (7) disciplinary infractions; (8) personal history derived from the PSR; (9) length of sentence and amount of time served; (9) inmate’s current age; (10) inmate’s age at the time of offense and sentencing; (11) inmate’s release plans (employment, medical, financial); and (12) whether release would minimize the severity of the offense.[168] Moreover, the Bureau must consider a list of questions about a prisoner’s history and behavior that can be answered in the affirmative or negative.[169] These factors above are not weighted against one another, nor is the Bureau required to apply all of them when examining an RIS application. Nevertheless, tasked with looking at individual records and applying these inquiries on case-by-case bases seems a cumbersome and lengthy process. On a macroscopic level, taking into consideration the swarm of RIS applications the Bureau is charged with reviewing, it might be easily overwhelmed, unable to review each compassionate release case.

I propose a solution that would reduce the number of RIS applications the Bureau reviews, utilizing computer software to expedite the hearings process. Admittedly, some factors listed above necessarily require human consideration instead of computer software – for example, comments from crime victims and whether early release minimizes the offense – but such a concession does not render procedural automation moot. When courts review prisoner RIS, there is a particular class that historically receives compassionate release. As discussed, the First Step Act emphasizes and addresses the health concerns of inmates with terminal illness, requiring the Bureau to process RIS of these individuals “not later than 14 days of receipt of a request for a sentence reduction submitted on the defendant’s behalf by the defendant or the defendant’s attorney, partner, or family member, process the request.”[170] (18 USC § 3582(d)(2)(A)). Cutting by more than half the standard 30-day time frame suggests that Congress anticipated the First Step Act to benefit this class of inmates.

The Bureau might consider adopting an automated request portal that aggregates all prisoner information, including the sort relevant to Bureau compassionate release guidelines.[171] If the Bureau fulfills its duties to “have charge of the management and regulation of all Federal penal and correctional institutions,” and to “provide for the protection, instruction, and discipline of all persons charged with or convicted of offenses against the United States,” the Bureau should have a significant information on each prisoner. The Bureau could theoretically centralize prisoners’ information and use such a computerized system to automatically process and respond to prisoner requests for early release without having to hear every request that it is presented.[172] Naturally, such a system might require the Bureau to gather additional information about prisoners and it would certainly require a significant degree of testing to ensure that the First Step Act is followed as intended by Congress.

Absolving the Bureau of its responsibility for the review of some RIS may seem troublesome and even invite criticism. Congress has assigned the Bureau to review each case pursuant to the aforementioned set of factors.[173] Where prisoners satisfy to a significant degree the factors outlined by Congress, requiring Bureau review of RIS essentially slows down procedure. Only those requests that meet a substantial number of prerequisites for RIS pass to the courts. The proposed solution does not remove from the review those requests that do not meet a significant number of prerequisites. These requests would be reviewed under existing methods by the Bureau. Such a change is far from radical – it simply automates the approval of requests that are likely to be granted by sentencing courts. After all, the Bureau plays the limited, but powerful role of passing along RIS, while the courts make the ultimate decision to approve or deny such requests.

When presented with RIS, courts look to the §3553(a) factors to determine eligibility for compassionate release, to the degree they apply to prisoner particulars.[174] Earlier, I discuss the pressing issue that §3553 language is out of date, leading some courts to call into question whether the language can be rectified with the First Step Act. For the sake of this proposition, I will presume that the language does not conflict with the First Step Act. When considering the sentencing guidelines, courts often look to the “nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant” and “the need for the sentence imposed” when confronted with compassionate release claims.[175] In doing so, a sentencing court looks to the crime committed, when it was committed, prisoner disposition, and the purpose of incarcerating the individual.[176] Courts, therefore, are required to make serious inquiries into prisoner recidivism should they receive commuted sentences. Concerns that frivolous requests satisfying automatic prerequisites can be remedied by the court review. In fact, courts already function in this capacity. If the Bureau fails to consider a frivolous request within 30 days, the requesting individual can move for a sentencing court to hear it.[177] Automation does not alter this procedure. For requests submitted, but that fail to meet prerequisites in the automated system, the Bureau would be charged with individually considering these requests before submitting to courts – the automation does not impact the sort of request that requires more careful deliberation and weighing of factors. Essentially, the structure would remain the same; the only change would permit automated forwarding of qualifying RIS to reviewing courts without delay.

Consider, for example, a terminally ill, 75-year-old prisoner with stage IV cancer and a history of asthma submits a request for compassionate release to the Bureau, citing the “extraordinary and compelling circumstance” that COVID-19 poses a serious threat to his health. Under the current framework, the Bureau can submit to the sentencing court the prisoner’s request as a motion from the Bureau for the prisoner’s release, but there is nothing preventing the Bureau from delaying such a process for up to two weeks.[178] Delay of requests of this sort serves no legitimate purpose for either the Bureau or for the inmates submitting RIS. Courts historically grant early release to individuals like the hypothetical prisoner. Under the automated request portal model, his RIS would meet certain standards the Bureau and courts often look for, and his request would automatically be submitted to the appropriate sentencing court for further deliberation.

Now consider the request for early release of a 40-year-old prisoner, serving a 10-year prison sentence for a drug offense, with a history of asthma and hypertension – the prisoner is not terminally ill, but infirmary records could affirm or deny an imminent threat to prisoner’s health. Similarly, the nature of his incarceration could affirm or deny the severity of his offense in relation to other drug offenses. This prisoner is less likely to have his request automatically submitted to a sentencing court. If the portal does not submit his request to a sentencing court, it would require deliberation by the Bureau. However, if the portal does forward the request to a reviewing court, it would be incumbent on that court to determine the veracity of the prisoner’s motion.

If properly implemented, an automatic request portal might be an invaluable tool to the Bureau that reduces the number of requests it is presented, allowing it to more thoroughly review requests of worthy inmates that don’t otherwise fit into the classical compassionate release category of prisoners. Inmates who are in dire need of compassionate release might have even quicker access to courts. Quicker access to courts may prove to be a legitimate means to proactively prevent the spread of contagious and dangerous diseases like COVID-19.

Gregory Hooks & Wendy Sawyer, Mass Incarceration, COVID-19, and Community Spread, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Dec. 2020), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/covidspread.html.

Office of the Inspector Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Pandemic Response Report 20-074, Status of CARES Act Funding as of June 12, 2020 (Unaudited) (June 2020), https://oig.justice.gov/sites/default/files/reports/a20074.pdf.

See Neal Marquez et al., COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Federal and State Prisons Compared With the US Population, April 5, 2020, to April 3, 2021, 326 JAMA 1865, 1865 (Nov. 9, 2021).

Fed. Bureau Prisons, Health Services Division, https://www.bop.gov/about/agency/org_hsd.jsp (last visited Nov. 13, 2021).

See 28 C.F.R. § 571.60 (2021); see also Fed. Bureau Prisons, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Program Statement Pol’y Number 5050.50, Compassionate Release/Reduction in Sentence: Procedures for Implementation of 18 U.S.C. §§ 3582 and 4205(g) (Jan. 17, 2019), https://www.bop.gov/policy/progstat/5050_050_EN.pdf.

18 U.S.C. §3582(c)(1)(A)(i) (2018).

See U.S. Sentencing Comm’n, Compassionate Release Data Report (Sept. 2021), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/compassionate-release/20210928-Compassionate-Release.pdf; see also The Answer is No: Too Little Compassionate Release in US Federal Prisons, Human Rights Watch (Nov. 30, 2012), https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/11/30/answer-no/too-little-compassionate-release-us-federal-prisons.

Sarah French Russell, Second Looks at Sentences Under the First Step Act, 32 Fed. Sent. R. 76, 76 (2019).

Keri Blakinger & Joseph Neff, 31,000 Prisoners Sought Compassionate Release During COVID-19. The Bureau of Prisons Approved 36., Marshall Project (June 11, 2021), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/06/11/31-000-prisoners-sought-compassionate-release-during-covid-19-the-bureau-of-prisons-approved-36.

Id.; see also Meghan Downey, Compassionate Release During COVID-19, Regul. Rev. (Feb. 22, 2021), https://www.theregreview.org/2021/02/22/downey-compassionate-release-during-covid-19/.

18 U.S.C. §§ 3553(a), 3582(c)(1)(A) (2018).

Neff & Blakinger, supra note 9.

Mike C. Materni, Criminal Punishment and the Pursuit of Justice, 2 Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 263, 265 (2013), https://hls.harvard.edu/content/uploads/2011/09/michele-materni-criminal-punishment.pdf/.

Id. at 295 (emphasis removed).

Paul Butler, Foreword: Terrorism and Utilitarianism Lessons From, and for, Criminal Law, 93 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1, 8 (2002).

Materni, supra note 13, at 264.

Id.

Id. at 265 (citing Hugo Adam Bedau & Erin Kelly, Punishment, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2010), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/punishment/).

Joseph A. Bick, Infection Control in Jails and Prisons, 45 Clinical Infectious Diseases 1047 (2007).

Taylor Walker, New Study Takes a Closer Look at Prison Commissaries Charging Inmates for Basic Needs, Witness LA (June 6, 2018), https://witnessla.com/new-study-takes-a-closer-look-at-prison-commissaries-charging-inmates-for-basic-needs/.

Fed. Bureau Prisons, Correcting Myths and Misinformation About BOP and COVID-19 (May 6, 2020), https://www.bop.gov/coronavirus/docs/correcting_myths_and_misinformation_bop_covid19.pdf.

Claire Hymes, Federal Prison Didn’t Isolate Inmates Who Tested Positive for Coronavirus, Report Finds, CBS News (Nov. 17, 2020), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/federal-prison-coronavirus-outbreak-fci-oakdale/.

State COVID-19 Data and Policy Actions, Kaiser Family Found. (Nov. 11, 2021), https://www.kff.org/report-section/state-covid-19-data-and-policy-actions-policy-actions/.

Erin K. Stokes et al., Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance – United States, January 22-May 30, 2020, 69 Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Rep. 759, 760 (2020), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/pdfs/mm6924e2-H.pdf.

Boehmer et al., Changing Age Distribution of the COVID-19 Pandemic – United States, May-August 2020, 69 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Rep. 1404, 1404 (2020).

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET): Data Through Week Ending in June 6, 2020, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (Nov. 13, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/images/need-extra-precautions/high-risk-age.jpg.

CDC has Information for Older Adults at Higher Risk, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (2020), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/images/need-extra-precautions/high-risk-80-percent.jpg.

See Overcrowding and Other Threats to Health and Safety, ACLU, https://www.aclu.org/issues/prisoners-rights/cruel-inhuman-and-degrading-conditions/overcrowding-and-other-threats-health (last visited Feb. 3, 2022).

BOP Modified Operations, Fed. Bureau Prisons, https://www.bop.gov/coronavirus/covid19_status.jsp (last updated Nov. 25, 2020).

See id.

Rachel L. Arco, When Conditions of Confinement Lead to Violence: Eighth Amendment Implications of Inter-prisoner Violence, 20 Hous. J. Health L. & Pol’y 101, 105 (2021).

Id.

Henrik Pettersson Byron Manley & Sergio Hernandez, Tracking Covid-19’s Global Spread, CNN (Nov. 13, 2021, 8:45 PM), https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2020/health/coronavirus-maps-and-cases/; see Adrianna Rodriguez & Rachel Aretakis, Coronavirus Updates: 1 in Every 15 Americans Has Tested Positive for COVID-19; Virus Claims Member of Famed Tuskegee Airmen, USA Today (Jan. 9, 2021), https://news.yahoo.com/coronavirus-updates-cdc-director-calls-145457997.html?soc_src=social-sh&soc_trk=tw&tsrc=twtr.

Kathryn M. Nowotny et al., Risk of COVID-19 Infection Among Prison Staff in the United States, 21 BMC Pub. Health 1, 1 (2021), https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12889-021-11077-0.pdf; see COVID-19 Cases, Fed. Bureau Prisons, https://www.bop.gov/coronavirus/ (last visited Sep. 3, 2021).

Id.

Brendan Saloner et al., COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons, 324 JAMA 602, 602-03 (2020); Covid-19’s Impact on People in Prison, Equal Just. Initiative (Apr. 16, 2021), https://eji.org/news/covid-19s-impact-on-people-in-prison/.

Id.

Boehmer et al., supra note 25, at 1404-09.

Inmate Age, Fed. Bureau Prisons (Nov. 6, 2021), https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_age.jsp.

Office of the Inspector Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 15-05, The Impact of an Aging Inmate Population on the Fed. Bureau Prisons (2016), https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2015/e1505.pdf.

Id.

2019 Fed. Bureau Prisons, FY 2019 Performance Budget 10.

Fourth COVID-19 Study from FAIR Health Examines Patient Characteristics, FAIR Health (July 16, 2020), https://www.fairhealth.org/article/fourth-covid-19-study-from-fair-health-examines-patient-characteristics (“The West was the region with the widest range of costs for COVID-19 hospitalizations. There, median charge amounts . . . [were] $93,459 for the over 70 age group.”).

See Roger I. Schreck, Overview of Health Care Financing, Merck Manual (Mar. 2020), https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/fundamentals/financial-issues-in-health-care/overview-of-health-care-financing.

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 103 (1976) (“These elementary principles [from the Eighth Amendment] establish the government’s obligation to provide medical care for those whom it is punishing by incarceration.”).

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-17-379, Bureau of Prisons: Better Planning and Evaluation Needed to Understand and Control Rising Inmate Health Care Costs (2017), https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685544.pdf.

Id. at 21.

Id.

CARES Act, H.R.748, 116th Cong. (2020) (enacted) (“$100,000,000, to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus, domestically or internationally, including the impact of coronavirus on the work of the Department of Justice. . . .”).

Joseph Neff & Keri Blakinger, Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort got to Leave Federal Prison Due to COVID-19. They’re the Exception, Marshall Project (May 21, 2020, 7:45 PM), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/05/21/michael-cohen-and-paul-manafort-got-to-leave-federal-prison-due-to-covid-19-they-re-the-exception.

CARES Act, H.R. 748, 116th Cong. § 12003(b) (2020) (enacted).

United States v. Brown, 457 F. Supp. 3d 691, 695 (S.D. Iowa 2020) (“The Attorney General has directed BOP to consider increased use of home confinement for at-risk inmates.”) (citing Memorandum from U.S. Att’y Gen. William Barr to Dir. of Bureau of Prisons (Mar. 26, 2020)).

COVID-19 Home Confinement Information, Fed. Bureau Prisons, https://www.bop.gov/coronavirus/index.jsp (last visited Jan. 17, 2021) (including individuals who have completed their sentences since March 26, 2020).

Neff & Blakinger, supra note 53 (suggesting the approval of home confinement for certain high-profile prisoners like former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort and Trump attorney Michael Cohen casts a shadow on the program).

See Fed. Bureau Prisons, FY 2020 Performance Budget 4 (2019), https://www.justice.gov/jmd/page/file/1144631/download#:~:text=For FY 2020%2C the BOP,%241.3 billion at 4 percent (suggesting that current imprisonment far exceeds the capacity in federal prisons).

Id.

Neff & Blakinger, supra note 53.

18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A) (2021).

The Answer is No: Too Little Compassionate Release in US Federal Prisons, Human Rights Watch (Nov. 30, 2012), https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/11/30/answer-no/too-little-compassionate-release-us-federal-prisons

Id. (“Over 21 years, from 1992 through November 2012, the BOP made only 492 motions for compassionate release, an annual average of about two dozen.”).

18 U.S.C.S. § 3582 (2021).

United States v. Ebbers, 432 F. Supp. 3d 421, 427 (S.D.N.Y. 2020).

Id.

18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A)(2021).

See United States v. Raia, 954 F.3d 594 (3d Cir. 2020).

Id.

Id.

Raia, 954 F.3d at 597 (showing the district court that first heard Raia’s case provided in a footnote that it would have placed the sixty-eight-year-old with Parkinson’s, diabetes, and heart disease in home confinement.).

United States v. Alam, 960 F.3d 831, 833 (6th Cir. 2020).

Carli Teproff, Woman Asked for Compassionate Release. The Prison Refused. She Just Died of COVID-19, Miami Herald (Aug. 10, 2020, 11:03 AM), https://www.miamiherald.com/news/special-reports/florida-prisons/article244718922.html.

18 U.S.C. § 3582 (2021).

Teproff, supra note 73.

Id.

Id.

Neff & Blakinger, supra note 53.

See id.

Damini Sharma et al., Prison Populations Drop by 100,000 During Pandemic, Marshall Project (July 16, 2020, 7:00 PM), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/07/16/prison-populations-drop-by-100-000-during-pandemic (“[H]ead counts have dropped largely because prisons stopped accepting new prisoners from county jails to avoid importing the virus. . . . So the number could rise again once those wheels begin moving despite the virus.”).

See id.

Sharma et al., supra note 80.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, United States Sentencing Commission Quarterly Data Report: 3rd Quarter Release 5 (2020), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/quarterly-sentencing-updates/USSC_Quarter_Report_3rd_FY20.pdf.

Fed. Bureau Prisons, Compassionate Release/Reduction in Sentence: Procedures for Implementation of 18 U.S.C. §§ 3582 and 4205(g) (2019), https://www.bop.gov/policy/progstat/5050_050_EN.pdf.

See id.; see also 18 U.S.C. § 3582 (2021).

See 954 F.3d at 596-97.

18 U.S.C. § 3582 (2021).

United States v. Ebbers, 432 F. Supp. 3d 421, 427 (S.D.N.Y. 2020).

Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Potential Airborne Transmission, Ctrs. For Disease Control & Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/scientific-brief-sars-cov-2.html (May 7, 2021).

See Georgia Slater, ‘Perfectly Healthy’ 18-Year-Old Dies of COVID-19 Three Days After Being Hospitalized, People (Dec. 31, 2020, 11:43 AM), https://people.com/health/healthy-18-year-old-dies-covid-19/.

Id.

Id.

FDA Takes Key Action in Fight Against COVID-19 by Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine, Food & Drug Admin. (Dec. 11, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19 (“[On December 11, 2020], the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued the first emergency use authorization (EUA) for a vaccine for the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in individuals 16 years of age and older. The emergency use authorization allows the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine to be distributed in the U.S.”); See also Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/moderna-covid-19-vaccine (last updated Aug. 31, 2021) (“On December 18, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the second vaccine for the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). . . . The emergency use authorization allows the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine to be distributed in the U.S for use in individuals 18 years of age and older.”).

Vaccine Development – 101, Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/development-approval-process-cber/vaccine-development-101 (last updated Dec. 14, 2020).

Food & Drug Admin., supra note 94.

Id.

Epidemics in U.S. History, Am. Soc. Hist. Project, https://ashp.cuny.edu/epidemics-us-history (last visited Feb. 6, 2022).

197 U.S. 11, 11 (1905).

Id. at 12-13.

Id.

Id. at 36.

Id. at 35.

Wendy K. Mariner et al., Jacobson v Massachusetts: It’s Not Your Great-Great-Grandfather’s Public Health Law, 95 Am. J. Pub. Health 581, 583 (2005).

Id. (internal quotations omitted).

Kevin M. Malone & Alan R. Hinman, Vaccination Mandates: The Public Health Imperative and Individual Rights, L. Pub. Health & Prac. 262, 272 (2003), https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/guides-pubs/downloads/vacc_mandates_chptr13.pdf.

David Roos, When the Supreme Court Ruled a Vaccine Could be Mandatory, History.com, https://www.history.com/news/smallpox-vaccine-supreme-court (last updated Aug. 2, 2021).

Mariner et al., supra note 104, at 582.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 584-85.

470 U.S. 753, 767 (1985).

569 U.S. 435, 435 (2013) (citing Winston v. Lee, 470 U.S. 753 (1985) (internal quotations omitted)).

Id.

U.S. Const. amend. IV.

569 U.S. at 435, 436.

Washington v. Harper, 494 U.S. 210 (1990).

Id. at 221-22.

Antietam Battlefield KOA v. Hogan, 461 F. Supp. 3d 214, 237 (D. Md. 2020) (citing Cent. Radio Co. Inc. v. City of Norfolk, Va., 811 F.3d 625, 633 (4th Cir. 2016)).

Wen S. Shen, Cong. Research Serv., LSB10300, An Overview of State and Federal Authority to Impose Vaccination Requirements 2 (2019).

Id. at 3.

Fed. Bureau Prisons, COVID-19 Vaccine Guidance 16, 25-26 (2021).

Id.

Id.

See id. at 26.

197 U.S. at 25.

18 U.S.C.A. § 4042(a) (West 2018).

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira, How did We Develop a COVID-19 Vaccine so Quickly?, MedicalNewsToday (Dec. 15, 2020), https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/how-did-we-develop-a-covid-19-vaccine-so-quickly.

Id. (“This is because of the complexity of vaccine development.”).

United States COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days (last visited Jan. 17, 2021).

18 U.S.C.A § 3582(c)(1)(A) (West 2018.

First Step Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-391, 132 Stat. 5194 (2018).

Fed. Bureau Prisons, supra note 85, at 6.

Stavros G. Memtsoudis et al., Obesity as a Risk Factor for Poor Outcome in COVID-19-Induced Lung Injury: The Potential Role of Undiagnosed Sleep Apnoea, e262 Brit. J. Anaesthesia e263 (May 1, 2020) (“A potential contributor to the high morbidity amongst obese patients might be the high prevalence of undiagnosed OSA.”).

The Ungers, 5 Years and Counting, Just. Pol’y Inst. 1, 17 (2018) (“Out of the 188 people released, only five have returned to prison for a violation of parole or a new crime.”).

Id.

Id.

Id.

See id.

Marissa Koblitz Kingman, Compassionate Release – Are You Eligible?, JD Supra (Oct. 27, 2020), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/compassionate-release-are-you-eligible-53024/.

Id.

See United States v. Jones, 482 F. Supp. 3d. 969, 976 (N.D. Cal. 2020).

Id.

Id.

Id. (emphasis added).

Id.

United States v. Young, 458 F. Supp. 3d 838, 844-45 (M.D. Tenn. 2020) (“a majority of the district courts that have considered the issue have . . . held, based on the First Step Act, that they have the authority to reduce a prisoner’s sentence upon the court’s independent finding of extraordinary or compelling reasons.”).

18 U.S.C.A. § 3582 (Westlaw through Pub. L. No. 117-41).

Kingman, supra note 141.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.